Article: Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 5/2018

CT-guided percutaneous drainage of a splenic abscess: case report and discussion of diagnostic and therapeutic options

Department of Radiology (Head of Department: Colonel (MC) Dr. C. Moritz) of the Bundeswehr Hospital Hamburg (Hospital Commander and Medical Director: Brigadier (MC) Dr. J. Hoitz)

Summary

Splenic abscesses are relatively rare and tend to develop more in patients with trauma, immunosuppression or as a comorbidity of endocarditis. The treatment of choice for a singular splenic abscess is CT- or sonography-guided percutaneous drainage. Surgical splenectomy is required if drainage is incomplete or a septate splenic abscess develops. Early and complete percutaneous drainage can therefore avoid the need for surgery in many cases. In this article, we present the case of a patient with a singular, non-septate splenic abscess which was successfully treated by CT-guided percutaneous drainage. Prognostic factors for the outcome of these patients comprise colonisation with gram-negative pathogens, multiple abscesses or a high APACHE (Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation) II score.

Key Words: splenic abscess, splenectomy, CT, CT-guided percutaneous drainage

Case Presentation

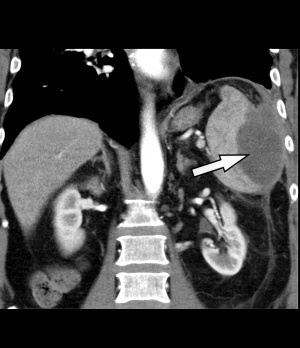

Figure 1: Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen: The left side shows an intra-perisplenic lesion (arrow) suspected to be an abscess (arterial phase).

Figure 1: Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen: The left side shows an intra-perisplenic lesion (arrow) suspected to be an abscess (arterial phase).

A 69-year-old male patient suspected of having a community-acquired pneumonia was referred to the emergency room of the Bundeswehr Hospital Hamburg by his family doctor. Clinical symptoms were a productive cough, no thoracic pain and a moderately elevated body temperature of 38.1 °C. Auscultation revealed vesicular breathing sounds. Laboratory tests revealed inflammatory parameters (CRP 233 mg/l [normal range: < 6 mg/l], PCT 0.18 ng/ml [normal range: < 0.0055 ng/ml], leukocytes 22.8/nl [normal range: 4 – 10/nl]). Digital projection radiography of the thorax in two planes showed no evidence of pulmonary infiltrates. The patient was admitted for inpatient treatment, and an antibiotics therapy with ampicillin/sulbactam and clarithromycin was initiated.

As part of the extended screening for infectious foci, a sonography of the abdomen was performed on the very first day of the hospital stay, revealing an etiologically indistinct, hypoechoic space-occupying lesion near the spleen.

This diagnostic procedure was immediately followed by a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen [Philips® Ingenuity 64 x 0.625 mm, SD 5 mm, KI 5 mm, Pitch: 1.142; KM dose 100 ml/Ultravist300®, flow rate 3 ml/sec]. The spleen showed a large, central hypodense space-occupying lesion measuring 9 x 8 x 6 cm (25 HE[¹]) with marginal, partly inhomogeneous, mostly linear contrast agent uptake, imbibition of the surrounding fat tissue and swelling of the retroperitoneum – taken as a whole, matching an abscess (Fig. 1). In response to more specific questions, the patient reported that he had suffered an abdominal trauma on his left side when he fell on a tree trunk 3 months earlier. We concluded that this trauma had caused a spleen haematoma that subsequently developed a superinfection including abscess formation.

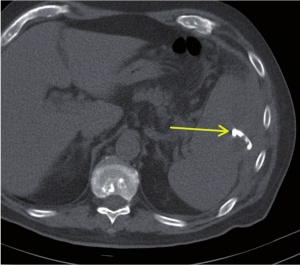

Figure 3: CT of abdomen: Post-interventional control shows that the position of the drainage is correct (arrow). The abscess drained completely.

Figure 3: CT of abdomen: Post-interventional control shows that the position of the drainage is correct (arrow). The abscess drained completely.

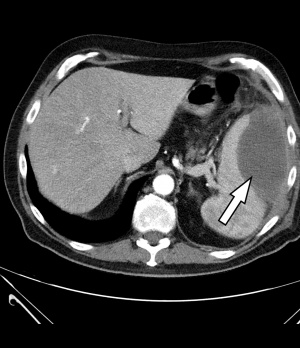

Figure 2: CT of abdomen with CT-guided percutaneous drainage based on Seldinger technique: This figure shows intercostal access control (arrow).

Figure 2: CT of abdomen with CT-guided percutaneous drainage based on Seldinger technique: This figure shows intercostal access control (arrow).

In an interdisciplinary consensus, intervention treatment by means of CT-guided drainage was administered on the same day. Under sterile conditions and local anaesthesia, a 12F pigtail catheter was inserted (Fig. 2) in dorsal position, guided by a CT scan using the Seldinger technique. Some 240 ml of purulent, cloudy, malodorous fluid were thus released. Samples were collected and preserved for microbiological diagnostics. The final computer tomographic position monitoring showed that the splenic abscess had drained and collapsed completely (Fig. 3).

During the hospital stay, the drainage was irrigated daily to prevent obturation of the lumen; there was no further secretion. Inflammatory parameters detected in laboratory tests were clearly regressive (CRP 17 mg/l, leukocytes 8.62/nl on the day of discharge).

A final CT (7 days after the drainage) confirmed the complete drainage and collapse of the abscess cavity (Fig. 4). The treatment of the splenic abscess was found to have been definitively successful and the drainage was removed. Follow-up care/CT checks were recommended because the subphrenic area was not sufficiently visible and therefore often difficult to map sonographically.

Anaerobes were suspected of being the pathogens of the abscess; however, no pathogen was detected in the microbiological analysis of the abscess content. The reason for this seems to be the anaerobes' pronounced sensitivity to transportation [2]. Furthermore, the antimicrobial therapy, the spectrum of which included anaerobes, was started because of the initial suspicion of pneumonia and then overlapped with the drainage treatment.

After a hospital stay of 9 days, the patient was discharged subjectively free of symptoms and in a good general condition.

Discussion

Incidence and Causes of Splenic Abscesses

Splenic abscesses are generally rare entities (incidence 0.14 % - 0.7%) [8], but must be taken into account in differential diagnosis considerations in the event of left-side abdominal pain.

Splenic abscesses usually develop via the haematogenous route from endocarditis or immunosuppression, alternatively after splenic infarctions or (blunt) abdominal traumas in the context of superinfections of parenchymal necrosis or haematomas [16]. The most important pathogens of splenic abscesses are Escherichia coli, staphylococci, streptococci, gram-negative anaerobes, or Candida species [10].

Splenic injuries do not have to be symptomatic and can, for example, be suffered without being unnoticed in combat situations (a fall, taking of cover, a collision with a vehicle) [24]. The possibility of an abscess developing from a haematoma caused by such trauma should be included in differential diagnosis considerations if appropriate symptoms are found.

Diagnostic procedures

In appropriate cases of clinical suspicion, non-contrast-enhanced and/or contrast-enhanced sonography and CT are used as diagnostic procedures. When compared to non-contrast-enhanced CT, non-contrast-enhanced sonography has a sensitivity of 76% versus 96% [2].

A sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 71% have been found for contrast-enhanced sonography [23]. The overall relatively low level of diagnostic reliability probably results from the limits to which the spleen can be assessed because it is frequently overlapped by intestinal gases and the lung.

The sensitivity and specificity of splenic abscess diagnostics with contrast-enhanced CT are 96% and 92% [6]. One advantage of CT is the reliability with which the surrounding structures can be assessed [13]; however, this involves exposure to ionising radiation (average mean effective dose per abdomen CT is 13 mSv) [5].

Treatment

Methods available for treating splenic abscesses are conservative antibiotic treatment, percutaneous drainage and splenectomy. In many cases, CT- or sonography-guided drainage is successful [4, 22].

The question of whether a single abscess or multiple abscesses are diagnosed is decisive for the choice of treatment. Furthermore, the size of the abscess, its location, septation, as well as the general condition and the overall clinical appearance of the patient must be taken into account in the therapy decision.

Percutaneous drainage should primarily be performed in the case of a single abscess as the clinical results are mostly better, whereas the data suggests primary splenectomy is right for multiple abscesses [14, 21]. The main complications associated with percutaneous drainage treatment are secondary haemorrhages, a puncture-related mortality rate of 0.7%, and unsuccessful puncture. The treatment also demands the patient's compliance, as he/she must be able to lie still while it is being performed [7, 9].

On the other hand, the disadvantages of the primary splenectomy, which include secondary haemorrhages, sepsis, wound healing problems and post-interventional intraabdominal abscess formation, have to be weighed up [17]. The relevant literature indicates a postsurgical mortality rate of 0.2 – 1% after laparoscopic or open splenectomy [12]. In addition, patients are susceptible to the Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI-Syndrome) [18].

Empirical studies [15] show that immediate complete drainage often decides upon the success of the treatment. If this is unsuccessful, splenectomy is necessary because, in many cases, the required complete drainage of the abscess cavity and the collapse of the walls is not achieved during the treatment without using suction.

Studies directly comparing the clinical findings of primary splenectomy with primary CT-guided drainage treatment have so far only been conducted retrospectively with small patient groups. Thus, ALVI et al. could not find any advantage in one of the methods in comparison with CT-guided drainage, splenectomy and sole antibiotic therapy. The superiority of primary splenectomy could only be shown for abscesses exceeding 10 cm in diameter [1]. SREEKAR et al. did not find any advantage in one of the three methods in a retrospective, non-randomised analysis either. However, the length of the hospital stay of 11.42 days for drainage treatment was significantly shorter than for sole antibiotic therapy (13.71 days) or after splenectomy (15.58 days) [19].

Negative factors for the outcome of all the treatment methods are a high APACHE II score[²], infection with gram-negative bacteria and multiple abscesses [3, 11]. In the present case, the patient had an APACHE II score of 8 and a single abscess. The decision was taken to perform primary drainage because there was no evidence of an infectious agent.

Core Messages/Conclusions

- In the diagnosis of splenic abscesses, CT is superior to sonography with regard to sensitivity and specificity.

- Unifocal large splenic abscesses should primarily be treated by means of percutaneous drainage.

- Initial empirical therapy must be performed and specific antimicrobial therapy is additionally necessary if pathogens are identified.

- Further advantages of this treatment are the retention of the organ and shorter hospital stays.

- Splenectomy is usually unavoidable if other treatment attempted is unsuccessful or the patient has multiple abscesses.

Literature

- Alvi AR, Kulsoom S, Shamsi G: Splenic abscess: outcome and prognostic factors. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2008; 18(12): 740 - 743.

- Çabadak H, Erbay A, Karaman K, Şen S, Tezer-Tekçe Y: Splenic abscess due to Salmonella enteritidis. Infectious Disease Reports. 2012; 4(1): e4.

- Chang KC, Chuah SK, Changchien CS et al.: Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of splenic abscess: A review of 67 cases in a single medical center of Taiwan. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006; 12(3): 460 - 464.

- Chou YH, Tiu CM, Chiou HJ et al.: Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures in splenic abscesses. European Journal of Radiology. 1998; 28(2): 167 - 170.

- Das M: Kumulierte Patienten-Strahlendosis bei wiederholten CT-Untersuchungen. Maastricht University Medical Center.: ECR-European Congress of Radiology., 6.3.2015.

- Davido B, Dinh A, Rouveix E: Abcès de la rate: du diagnostic au traitement. La revue de médecine interne. 2017; 38(9): 614 - 618.

- Gupta S, Wallace MJ, Cardella JF et al.: Quality Improvement Guidelines for Percutaneous Needle Biopsy. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology 2010; 21(7): 969 - 975.

- Hung SK, Ng CJ, Kuo CF et al.: Comparison of the Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis Score, Modified Early Warning Score, Rapid Emergency Medicine Score and Rapid Acute Physiology Score for predicting the outcomes of adult splenic abscess patients in the emergency department. PLOS One. A Peer-Reviewed. Open Access Journal 2017; 12(11): e0187495.

- Hunold P, Wiggermann A: Radiologisch-interventionelle Drainage bei abdominellen Abszessen. Viszeralmedizin 2013; 29: 14 - 20

- Kayser FH, Böttger EC, Haller O, Deplazes P, Roers A: Taschenlehrbuch Medizinische Mikrobiologie. Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag, 2014; S. 676.

- Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE: APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1985; 13(10): 818 - 829.

- Kojouri K, Vesely SK, Terrell DR et al.: Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review to assess long-term platelet count responses, prediction of response, and surgical complications. Blood. 2004; 104(9): 2623 - 2634.

- Moll R, Sailer M, Reith HB, Schindler G: Alternative zum chirurgischen Vorgehen – CT-gesteuerte Drainagenbehandlung der Milz bei Abszessen und Hämatomen. Klinikarzt. 2004; 33(6): 183 - 188.

- Ng KK, Lee TY, Wan YL et al.: Splenic abscess: diagnosis and management. Hepatogastroenterology 2002; 49(44): 567 - 571.

- Prokop M, Galanski M, Schaefer-Prokop C et al.: Ganzkörper-Computertomographie: Spiral- und Multislice-CT. Stuttgart, New York.: Thieme., 2007, S.186.

- Rotman N, Kracht M, Mathieu D, Fagniez PL: Diagnosis and Treatment of Splenic Abscess (about 11 cases). Ann Chir. 1989; 43: 203 - 206.

- Seufert A, Encke RM: 47. Komplikationen nach Splenektomie. Langenbecks Archiv für Chirurgie. December 1986, Volume 369: pp 251 - 257.

- Sinwar PD: Overwhelming post splenectomy infection syndrome – review study. International Journal of Surgery. 2014; 12(12): 1314 - 1316.

- Sreekar H, Saraf V, Pangi AC: A Retrospective Study of 75 Cases of Splenic Abscess. Indian Journal of Surgery. 2011; 73(6): 398 - 402.

- Suerbaum S., Hahn H., Burchard GD, Kaufmann SHE, Schulz TF: Medizinische Mikrobiologie und Infektiologie. s.l.: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

- Taşar M, Uğurel MS, Kocaoğlu M, Sağlam M, Somuncu I: Computed tomography-guided percutaneous drainage of splenic abscesses. Clinical Imaging 2004; 28(1): 44 - 48.

- Thanos L, Dailiana T, Papaioannou G et al.: Computed tomography-guided percutaneous drainage of splenic abscesses. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2002; 179: 629 - 632.

- Von Herbay A, Barreiros AP, Ignee A et al.: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography With SonoVue. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2009; 28: 421 - 434.

- Waseem M, Bjerke S: Splenic Injury. In: StatPearls (Internet) 2018; https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441993/ (Accessed: 25 March 2018)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Image source for all figures:

Bundeswehr Hospital Hamburg

Citation mode:

Kley C, Moritz C, Ritzel RM: CT-Guided Percutaneous Drainage of a Splenic Abscess: Case Report and Discussion of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Options. Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 2018; 62(5): 130 - 133.

For the authors:

Christiane Kley, Captain (MC)

Bundeswehr Hospital Hamburg, Department VIII

Lesserstraße 180

22049 Hamburg

E-Mail: [email protected]

[1] HU = Hounsfield units; unit of measurement for the grey scales of a CT scan; the higher the value, the lighter the gray scale. This means that the X-rays are more strongly absorbed by the tissue; the gray scale for water is defined as 0 HU, while bones range between 500 and 1,500 HU.

[2] The score calculated from APACHE used in intensive care medicine serves to predict the probability of survival of intensive care patients. This scoring system includes information on the patient's age, current results and anamnestic data. The score ranges from 0 to 71 points.

Date: 06/14/2018