Article: Z. VEKERDI, A. GROSZ, L. SVED, P. BAZSO, G. K. SZUGYIEZKI (HUNGARY)

Hungarian Experience in Integrating Military and Civilian Medical Capabilities - Competence as a Driving Factor

The article highlights the issue from a strategic point of view and does not go into details of its operational and tactical aspects. MCIF readers get a short introduction, background and the main requirements for a comprehensive approach to integration of military and civilian medical capabilities, using competence as a driving factor, within one organization, under military management.

The authors intend to generate discussions that can contribute to development of recommendations how to approach integration of civilian and military medical capabilities within one organization. These recommendations will inevitably go beyond national aspects of integration efforts, defining the appropriate level of interaction between the political, military and civilian players.

The aim is to identify, on a demand-driven basis, how military and civilian actors, integrated within one organization, can help meet the needs of the population at risk within the framework of military management and mixed, civilian-military financing, while supporting the intention of decision makers to sustain quality health care in a resource limited environment.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF THE INTEGRATION

The Hungarian Defence Forces (HDF) and its predecessors have always been playing an important role (though in different scales and for different reasons) in health care of the civilian public. During the Turkish occupation in the 16th and 17th centuries every monastery-hospital was destroyed in Hungary. At the end of the Turkish reign, in 1686, the first hospital re-established during the siege of Buda was a military one, situated on the Margaret Island. This fact has a more than symbolic meaning for the future relationship and history of military medicine with the civil population.

During the revolution and fight for freedom against the Habsburgs (1848-49), casualties were transported to so-called war hospitals usually established together with the existing civilian hospitals of the different cities. By May 1849, 82 such war hospitals were functioning, using the civilian hospital facilities. The Hungarian Royal Defence Forces provided treatment also for the soldiers` relatives, which resulted in establishment of new departments and outpatient clinics in military hospitals, like gynecology.

After World War II, the Hungarian armed forces were enlarged into a force of unreal size, with a large medical service supporting it. By January 1st 1950, the number of military hospital beds reached 3570, and it was further enlarged, reaching the number 4220 in 1953. Not only the military medical infrastructure and the number of hospital beds were increased, but also the quality of treatment was improved by “inviting” (through forced conscription) the best medical professionals to serve in the army. These highly qualified professionals realized the need for broadening the scope of medical treatment procedures beyond the traditional ones in the military (like treating varicose veins, hernia, tonsillitis, or flatfoot). They have insisted on opening military hospitals also for the civil population (and allocating 30 to 50 percent of the existing beds for these purposes). In 1952, already civilian patients occupied 30 percent of the beds in the central military hospital. This was also the time when the National Traumatology Centre was created, and the senior surgeon of the Hungarian People`s Army was appointed as its director. After the central military hospital in Budapest, other military hospitals also were included into the territorial medical duty system for the civilian population in the areas of traumatology, burn injuries, toxicology and other emergency services. The 6th Military Hospital in the city of Győr was built in 1984, parallel to opening a civilian hospital in the same district, where the departments of traumatology, neurosurgery, burn injuries, oral surgery and cardiology were run by military medical personnel. Later this was the first military hospital that became victim of the military reform. In 1996 it was handed over to (integrated into) the civilian hospital, together with its specialized staff and infrastructure, 15 people of which were veterans of the first gulf war.

When reconstruction of the central military hospital in Budapest started in 1986, no one could imagine that in 21 years (a period full of hesitation regarding the hospital concept and its construction) the military hospital becomes basis for a great example of civil-military cooperation.

ECONOMIC CRISIS AS AN ACCELERATOR FOR INTEGRATION

The decisive factor in sustainability of a medical facility is still the gap between the demand and possibility. The former is three fold. The patients, medical personnel and the budget providers all have their own demands, while the opportunity is predetermined by the budget available, since it becomes a constraint whenever a medical facility wants to hire medical specialists, introduce incentives for retaining its medical personnel, acquire and implement new technologies, or cover surge needs for treatment with medical consumables etc.

The so called State Health Centre was established on July 1st 2007, as a result of the integration of four (civilian and military) medical institutions. The budget of this State Health Centre actually depends (almost directly) on the National Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in a way that it comes from two main sources. The bulk of it is reimbursement paid by the State Health Insurance Company for health and medical services performed and provided by the medical facility, while running and maintenance costs are covered by the owner, the Ministry of Defence. Both budget providers are state owned and thus their financial opportunities depend on GDP. The gap between demand and opportunity results in challenge to keep up with technical developments in medicine at constant need for more resources, while the society is aging. Elderly people require longer treatment that is expensive and more frequently required than for patients of younger generations.

Some obstacles that pushed decision makers towards searching for and creating new solutions for sustainability before the integration process began:

- military hospitals that treat only military patients and casualties cannot provide the right scope of medical cases to maintain knowledge, skills and training for medical personnel

- military hospitals with limited scope of medical cases face serious difficulties in recruiting and retaining medical personnel, thus becoming ineffective and unsustainably expensive

- limited budget and growing costs for treatment force decision makers more and more to reduce capacities and capabilities of the (military) treatment facility

- inadequate human and financial resources result in either closing the military hospital or integrating it into a larger civilian facility

- integration of a military hospital into a civilian facility creates new obstacles for the military - e.g. civilian hospital management falls outside military command and control which hinders coordination of military tasks between troop level (Role 1, 2, 3) and central level (Role 4) treatment facilities

COMPETENCE AS A DRIVING FACTOR IN INTEGRATION

Competence (or competency) is the ability of an individual to do a job properly. A competency is a set of defined behaviors that provide a structured guide enabling the identification, evaluation and development of the behaviors in individual employees.

A competent person or system possesses all the required skills,knowledge,and qualification to act effectively in a situation. In a hospital the same subordinated competence system can be observed. A hospital must be competent at all levels, from the strategic level of management to the tactical level of daily practices. To acquire competency, it is necessary to keep in practice all required skills. Consequently, there is an optimal case number where competency may be formed and maintained. Running a real multidisciplinary hospital on an appropriate competency level takes more than 1 million people to be assigned to that facility for treatment. But the sheer number of population at risk is not enough. How can a hospital ensure the competence of those specialists, who cannot meet the optimal number of cases? In military health care the focus is on the same question: how to master competencies in peacetime, how can a medical officer stay combat ready?

In Hungary, military health care, police forces health care and health care for personnel of the State Railway Company traditionally retained independence from the civilian health care system, while – as a consequence of the economic crises – the population at risk in all three organizations was constantly reducing. This and the shrinking budget led to an unsustainable medical competence in the separated medical services. As a result, the integration of hospitals took place in 2007. Civilian and military hospitals were integrated into one huge facility, the State Health Centre, but this time under the auspices of the Ministry of Defence. The scale of tasks has substantially changed for the State Health Centre. The population assigned to this facility for treatment counted 1.2 million people.

DISCUSSION

Beyond the above concept, competency has several other relevant scopes when speaking of health care. Medical competence has economical and professional approaches simultaneously.

The world is changing and our medical institutions are to meet the ever changing requirements among ever changing circumstances. In health care, a special landmark was the appearance of high technology in medicine in the early 1970`s. The use of computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and molecular genetics resulted in price-boom, which demanded changes in the funding of health care. The problem was that executives clearly saw the costs rising, but they didn't understand all the products and services that medical facilities delivered to them, and they couldn't see how costs were linked to those deliverables. As a result, the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system has been implemented. The DRG system intent was to identify the "products" that a hospital provides.

Parallel to the worldwide changes in national economies (and consequent challenges towards national GDPs), military health care was strongly influenced by the development of military technology. Limited military budgets and new military technologies gradually reduced the need (and opportunity) of human resources, so national armed forces started to reduce their personnel. The 150-thousand strong Hungarian armed forces of the cold war era was transformed into the Hungarian Defence Forces (HDF) with maximum 29700 personnel by 2013. Similar tendencies were noticed in the police forces and at the State Railway Company. As the most important factor in sustaining competence, the group of entitled personnel (assigned for treatment) gradually decreased starting from an average of 150 thousand per hospital in the early 1970`s, to an average of 30 thousand per hospital in 2006. Meanwhile, the health care costs started to run radically high. This means that the number of potential patients fall under the critical level, where it becomes both professionally and economically impossible to sustain the separate institutes as independent medical facilities.

Professional competency, or preparedness, could not be ensured for medical officers among these circumstances. Specialists were unable to perform the optimal number of procedures in critical for the military specializations like Emergency medicine, Anesthetics, Intensive Care Therapy, Poly-trauma, Neuro-trauma, Burn injuries, Infectious Diseases, Toxicology, Surgery, or Dermatology. As a consequence, bed usage rates fell below 60 % at the separate hospitals, and of course the number of patients in each hospital could not ensure the appropriate level of competency for medical personnel. These separate medical institutions became unsustainable, so due to the economical incompetency, institutional and professional incompetency started to form.

After the integration, the new facility (under the auspices of the Ministry of Defence) became a tertiary level referral centre for a 1.6 million population of central and northern Hungary, while several smaller hospitals were closed in the region for unsustainability. As expected, the medical personnel of the new facility deals now with much larger numbers of patients, which is helpful in maintaining their skills.

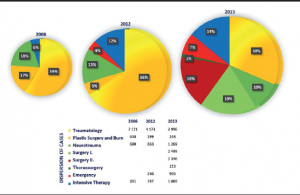

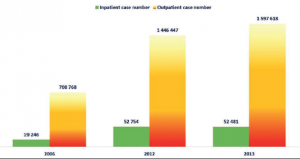

Before the integration, in 2006, the common Case Mix Index (CMI) for the four individual hospitals was 0.92178. The new medical centre in 2012 produced a CMI equal to 1.34324. The total number of beds of the four separate hospitals was 3000. The new facility after the merge had 1177 hospital beds.

The military focus of the State Health Centre (health and medical support to the mission of the HDF) needed to be reflected also in its name and structure; therefore, from February 1st 2013 the facility is called Medical Centre, HDF. The facility has its commander (a non medical military professional) and supporting staff (headquarters). The first deputy of the commander is the Surgeon General, and the second deputy is the director of the military hospital within the Medical Centre, HDF. This structure allows separation of functions and burden sharing along the military and medical command & control tasks and responsibilities.

As discussed, the sheer number of patients is very important (see Figure 3), but additional efforts are required to ensure sustainment and development of professional competence. Medical staff of the facility needs the opportunity to manage and practice in rare medical cases, important for military tasks. For instance, the management of our hospital arranged that all civilian patients with gunshot wounds from Budapest and the surrounding area should be taken by the state ambulance service to the Medical Centre of the HDF for treatment, so as to enable medical officers to enhance their skill in this special field.

A shift in achieving sustainability has started. The integration created a framework for the required changes, but the desired goal of sustainability (in financial and human resources) was still far away. Ground values of the new organization were the concentrated work force (3500 staff) and the enlarged population at risk (more than a million people) assigned for treatment to the new institution.

The next step to become sustainable was to have a visionary and delivering policy. The Medical Centre, HDF is part of the force order that is it is listed among the military capabilities designed and designated to defend independence, territory, airspace, population and material goods of Hungary in case of aggression – in accordance with the provisions of Article 51 of the Charter of the UN. The main objective with establishment of the Medical Centre, HDF was to have the proper skill set (competence) in possession and exploiting it also for the military purpose. Therefore, the new medical facility needed a visionary policy in a way to set priorities for national and regional level tasks, and also globally. At the same time, the new policy needed to be recorded not only on paper, but also to be reflected in the mind, heart and everyday practice of the staff, to inspire them and improve their organizational performance. So, what was required is not only a visionary but also a pragmatic, delivering policy. Therefore, through the military culture, clear expectations and descriptions about the common line of efforts are given to every sub-organization of the medical centre and for its every department and every staff member. Statements are provided (via standing operating procedures and job descriptions) with a detailed description of how the organization and its staff should work. Basic values of the organization are transformed into behaviors one can teach, model, and measure (e.g. via military health promotion programs). This requirement and opportunity are described in the military medical career model.

Invest in people and build people. Before the integration, all four hospitals had their own culture and heritage that they brought with into the new organization. The Police Force Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior Affairs and the Military Hospital had good experience, practice and skills in ensuring and providing deployable medical support and also medical services for (VIP) people, while the Railway State Hospital was good in handling large numbers of patients, and the University Hospital had the highest quality workforce , with considerable teaching and scientific experience. The idea after the integration was to build and nurture connections with each other in performing primary tasks of the organization. This was ensured through bringing the best of the different cultures and heritage together. The military culture brought additional financial resources, command and control skills (to take decision and act), military patriotism and passion. The civilian culture contributed to basic values of the new organization e.g. with external audit requirements and promising best practices in postgraduate medical education and training. As a result, the Medical Centre, HDF became an accredited education and training facility, and is the teaching hospital of the Semmelweis University`s Faculty of Medicine. Bringing military and civilian culture together within one facility however requires also a great portion of tolerance (both from staff and patients). Certain priviledges had to be given up during the integration process. Military and police force patients e.g. get no extra attention because of their ranks.

Our experience shows that most contributing factors to success are leadership philosophy (visionary and pragmatic policy), competence of the work force, and stable financing. The final step was (and still remains) to ensure the necessary financial budget for the new facility.

Medical procedures are generally underfinanced in Hungary. Costs of the particular medical procedures are higher than the reimbursement paid by the State Health Insurance Company. Therefore, the more procedures a medical facility performs the higher is the deficit it generates. Since this deficit cannot grow for ever (since suppliers are not tolerating it) from time-to-time the State Health Insurance Company tries to mitigate deficit of hospitals under its supervision (depending on available financial resources). The Medical Centre, HDF is supervised by the Ministry of Defence. Therefore, the State Health Insurance Company prefers providing extra aid from its scarce financial resources to civilian hospitals first, leaving the task and burden of consolidating the financial situation of our facility to the Ministry of Defence. Financial resources redirected by the Ministry of Defence from military tasks to cover deficit of the Medical Centre, Hungarian HDF, creates tension within the military.

The State Health Insurance Company tries to keep hospitals` deficit within manageable borders by limiting the number of procedures reimbursed by the company per month. This is valid for elective procedures only, and creates waiting lists in all. When a hospital reaches its limit of procedures per month, it tries to redirect even emergency cases (as much as possible) to higher level medical facilities, thus avoiding performing over-the-limit procedures (e.g. supporting X-ray or laboratory procedures). This approach is not an option for a referral medical facility, like ours, since in several cases there is simply no higher level referral centre where a patient could be redirected. Administrative procedures aiming to reduce the number of citizens assigned for treatment (population at risk) or to decrease the number of procedures performed per month are also not an option, and therefore unacceptable for us, since they undermine our efforts in maintaining and developing competence of our facility and its staff.

There is a review process taking place now, aiming to identify and eliminate unnecessary duplications in military and civilian capabilities within our facility, e.g. in the areas of research, training, management, logistics or laboratory. Another mitigating option is selling of spare (unfinanced by the State Health Insurance Company, over-the-limit) treatment capacities to private insurance companies who offer private health insurance for their clients. There is already such a mutually beneficial contract in place with one of the international insurance companies. Administrative procedures can –to a certain limit- contribute to mitigating deficit of our facility, but definitely cannot solve it alone. The only sustainable solution is proper reimbursement for medical services and procedures (by the State Health Insurance Company), which will happen only when growth in GDP makes that possible. Long term burden posed over the Ministry of Defence to redirect financial resources from military tasks to cover deficit of the Medical Centre, HDF, may erode commitment of the Ministry of Defence towards military management, and has the potential risk of transferring the facility to civilian control.

SUMMARY AND WAY AHEAD

While the last six years since 2007 provided vast experience in health care management of the integrated facility and have changed the way we think of our (military and civilian medical) role in national health care, there is room for further improvement. Most of the time this means adjustment to the changing conditions and environment in which competence provides quality criteria and a management tool for military and civilian medical personnel in their daily health care activities.

Further significant leverage in these adjustment efforts can be achieved in the following areas:

Leadership role

- Periodic review and update of health care policy, doctrine and directive

- Develop an institutional framework for competence management

- Practice a management style where the military leadership can effectively command and control both military and civilian medical personnel within the facility

- Train key medical personnel in management and financial issues

Communication

- Improve communication with the media

- Report periodically to military, civilian and political decision makers on health care activities and achievements of the facility

- Information sharing and reach back between the facility and its national partners

“SWOT” ANALYSIS

Strengths

-the civilian culture applied in daily health care practice brings flexibility in interpersonal relationships, assured quality system through external audit, education and training requirements and the framework of professional development through scientific activities

-the military culture applied in management provides clear tasks, values, expectations, deadlines and accountability for both military and civilian personnel

-better sustainability in rotations of medical personnel on deployments

-a broad range of prevention, treatment, training, research and medical logistics capabilities, concentrated within a single medical facility, readily available for defence security tasks

Weaknesses

-underfinanced treatment procedures

-weak incentives for recruitment and retention of medical personnel

Opportunities

-introduction and implementation of the military medical (career) model

-adjusting budget to financial requirements

-spare (unfinanced, over-the-limit) treatment capacities might be sold to insurance companies

Threats

-underfinanced health care results in linear increase of deficit that becomes unmanageable

-reduction in treatment capacities (practiced in an attempt to reduce budget deficit) undermines efforts to develop and maintain competence, corrodes medical staff commitment to the facility and results in unsustainable human resources

REFERENCES [email protected]

Authors:

Colonel Zoltan Vekerdi, MD, Medical Centre, Hungarian Defence ForcesHead, Defence Health Institute, Medical Centre, Hungarian Defence Forces (1134 Budapest, Róbert Károly krt. 44, Hungary)

(First and corresponding author)

Co-Authors:

Brigadier General, Professor Andor Grosz, Medical Centre, Hungarian Defence Forces

The Surgeon General, Hungarian Defence Forces

Lieutenant General (ret.) Laszlo Sved, MD, Ph.D.

Peter Bazso, MD, Medical Centre, Hungarian Defence Forces[1]

Senior Advisor, Medical Centre, Hungarian Defence Forces

Szugyiczki - Győrdi Katalin

Department for Planning and Coordination, Ministry of Defence, Hungarian Defence Forces

Date: 02/14/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (4/2013)