Article

THE CULTURAL CHALLENGE OF LEADING IN MILITARY MEDICINE

Lt Gen (Rtd) Professor Martin CM Bricknell CB OStJ PhD DM MBA MA MedSci

INTRODUCTION

We all lead teams. In the military, our team is normally identifiable even if the members come from different backgrounds. At the beginning of our career, these teams are usually small and it is easy to communicate at a personal level with each member. As we progress, we lead larger teams. As an example, I commanded a field hospital on a major military exercise to the Middle East. This was much more challenging because, although the leadership structure of about 100 people came from my own unit, we were reinforced with nearly 300 additional personnel from the Navy, Army and Air Force and from other nations. Since then I have led different sized teams from a variety of backgrounds in both national and multi-national organisations. This experience has led me to reflect on the influence of the cultural context at both the individual and organisational level while I led them to meet the needs of our patients. This article is based on a presentation on ‘The Cultural Challenge of Leading in Military Medicine’ delivered at the 43rd International Committee of Military Medicine World Congress of Military Medicine in May 2019.

All military medical services have the following strategic challenge: to deliver a garrison health system that delivers military personnel fit for role and, concurrently, to train and operate a deployable medical system that can care for casualties of conflict on military operations. We do this within a complex cultural environment of military, professional and organisational identities. At present, almost all military medical services are undergoing some form of change as our nations adjust to threats in the international security environment and how they wish to use their armed forces. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the factors that influence culture within military medical systems in order to support organisational change.

METHOD OF ANALYSIS

The quote ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’ is often attributed to Peter Drucker, a famous management academic. It emphasises the importance of the softer, emotional context in which humans operate within an organisation and the influence of culture on the behaviour of an organisation as it responds to challenge and change. This paper is structured around the concept of a ‘cultural web’ as described by Johnson and Scholes in the 1990s (1).

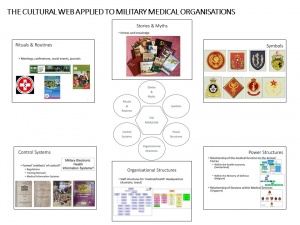

This is a model that identifies 6 domains that make up an organisation’s culture. These are: symbols, power structures, organisational structures, control systems, rituals and routines, stories and myths. By examining each of these, it is possible to identify the artefacts that influence the culture of an organisation. At the centre of the model is the Organisational Paradigm, or unifying purpose. A change in an organisation will occur more easily if the cultural domains and the organisational paradigm align with the intended direction of travel. I will use the Cultural Web as a framework to identify influences on the culture of military medical organisations. This paper is based on case examples drawn from information on each nation’s military medical service published in the Almanac of Military Medicine (2). The Cultural Web as applied to military medical organisations is shown at Figure 1.

Figure 1 – The Cultural Web applied to Military Medical Organisations

CONSIDERATION OF CULTURAL DOMAINS

Symbols. Let’s start by considering ‘Symbols’. Symbols are the images that we use to represent our teams. The range of symbols provide significant insight into ‘tribal’ groups within organisations. They are often much more prominent in military medical organisations than comparable civilian ones.

Using the UK Defence Medical Services as an example, there are badges that represent different groups of people. Badges define individual organisations, such as the Joint Medical Group, the Institute of Naval Medicine, 2nd Medical Brigade or the Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron. These create a sense of identity for members of each organisation – though there may be further internal sub-divisions. There are also badges that identify the medical services in the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. However, the medical services’ identity in the Army is based on professional badges for nursing (Queen Alexandra Royal Army Nursing Corps), dentistry (Royal Army Dental Corps) and veterinary services (Royal Army Veterinary Corps); with the Royal Army Medical Corps covering all other professional groups including doctors, medics, radiographers, paramedics, physiotherapists, pharmacists etc. Thus a single individual may concurrently associate their loyalty to their organisation, their profession and their service.

Figure 1 shows some badges of military medical services from the Almanac. Most nations have a badge for their military medical services. There is some common symbology including: the rod of Asclepius, the Caduceus, the Red Cross or the Red Crescent. When analysing culture in military medicine, it is often helpful to understand how badges are used to represent different organisational structures and professional groups.

Power structures. The next domain to consider is ‘Power Structures’. Power is a complex fusion of formal authority, informal influence and the control levers that enable leaders to direct their subordinates. There are two levels of power that affect military medical services. The first is the strategic relationship of the medical services to the Armed Forces. This can be divided into relationships with the wider national health economy and relationships within the Ministry of Defence. The national source of power relates to the role of the military medical services within a nation’s health economy and the authority of the Surgeon General to have a seat at a senior, national, level. In some nations the Surgeon General is a member of national, strategic, cross-department committees. In other nations, the Surgeon General is subject to oversight by other cross-ministerial boards or committees. An example is the role the military Surgeon General in the Swiss Federation (3). This position includes several roles: the Head of the Armed Forces Medical Service; the Commissioner of the Federal Council as Head of the Coordinated Medical Services of all national medical resources in response to a nationwide crisis; the Medical Advisor to the Chief of the Armed Forces and to the head of the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport; and finally responsibility for the medical and technical standards of the Armed Forces Medical Service and of the Red Cross Service organisation according to Swiss laws and civilian standards.

Within the Armed Forces, most Surgeons General have the dual role of being the senior adviser on health matters to the Ministry of Defence and also the head of the staff branch within the Ministry of Defence for the delivery of health services. The power of the Surgeon General is determined by his/her authority to speak directly and independently to the senior leaders. Some can report direct to the Minister of Defence; others have to report through Personnel or Logistic staff. In Belgium the Surgeon General is the based in the Defence Staff reporting through the Vice Chief of Defence Staff to the Chief of Defence. Separately, there is a Medical Component Commander acting as leader of all medical services with a status similar to the Land, Air and Naval Components (4).

The second power structure is based on the relationship between the medical staff in the Ministry of Defence, any Joint organisation and the Service medical services. In some nations, the Surgeon General is solely a co-ordinating staff authority (with responsibility for medical policy and clinical coherence), with the Chiefs of the Navy, Army and Air Force owning the medical organisations for their Service. In other nations, the Surgeon General owns all the military medical manpower and provides the people into the organisational structure of the Services when needed. There is a global trend to make military medical services more Joint and to reduce duplication of medical activities between Services. In the Republic of Singapore, the Singapore Armed Forces Medical Corps is responsible for medical policies and commands the Military Medicine Institute and the Force Medical Protection Command (5). The Military Medicine Institute is responsible for primary care medical centres and dental centres to the Singapore Armed Forces. However, the Army Medical Service, Air Force Medical Service and the Navy Medical Service have separate identities working to each military service.

Organisational Structures. We will now consider ‘Organisational Structures’. This analysis considers how military medical services are internally organised and the staff structures that provide the leadership for the military medical function. Most nations have separate staff branches for operational medical support, garrison medical support, medical policy and force health protection, medical personnel, and medical logistics. There is also an increasing trend to have a discrete staff branch for medical information systems. As an example, the Australian Joint Health Command is divided into staff branches for health services (organised on a regional basis), force health, health capability, policy and strategy, and finally resources and plans (6). There is no separate staff structure that commands medical services in the Army, Navy or Air Force though there is a designated senior officer who is the Director General for medical advice to the head of each of the military services. The staff structure for the medical services in the State of Israel has 5 departments (7). The Military Medical Services Department covers: healthcare, preventive medicine, and medical classification. The Combat and Operational Medicine Department covers trauma and combat medicine, NBC medicine, operations, and doctrine and training. The Chief of Staff covers manpower, logistics, finance, medical information and medical engineering. There is a Military School of Medicine within the Hebrew University covering research and professional education and the Military Medical Academy and Training Centre provides courses for medics, paramedics and practical field skills for all professional groups. These examples show that there is wide international consensus on the core medical staff functions required to lead and manage a military medical service.

Control systems. The next domain to consider is ‘Control Systems’. There are many formal systems that organisations use to direct and co-ordinate the activities of medical personnel within the internal structure of a military medical system. The image on Figure 1 shows some examples of historical regulations, training pamphlets and guidelines within the UK military medical system. The authority for the existence of most nations’ militaries is based on military law. This is usually translated into internal regulations that describe the business processes for directing the Armed Forces. The example is the 1938 edition of Regulations for the Army Medical Services which was first published on the formation of the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1898. Handbooks and manuals used in training set the baseline of knowledge for members of the organisation. The example is the 1952 version of RAMC training that set the curriculum for first aid and nursing for medics. There may be very specific instructions for key ‘drills’ such as the Battlefield First Aid training manual (published in the 1990s); or guidelines for clinical practice across the medical system – such as Clinical Guidelines for Operations that were first published in 2004. For the future, we also need to consider the implications of electronic medical information systems as an emerging mechanism for internal control of military medical services.

Rituals and routines. In addition to formal control systems, most organisations evolve informal systems of human collaboration based around ‘Rituals and Routines’. Indeed, these are often more powerful in building the human relationships that drive the outputs of an organisation than formal control systems. Examples are meetings, conferences, dinners and academic journals. These help to build the sense of identity and to form the social relationships within the team. Notably in military medicine, many nations and organisations sponsor an academic journal to communicate emerging intellectual thinking prior to incorporation into formal documents. These also provide a medium for internal communication across the organisation. Figure 1 provides examples from the International Committee of Military Medicine and Medical Corps International Forum.

Stories and myths. The final domain is ‘Stories and Myths’. This domain represents the deep, intangible heritage of the military medical system and the creation of an identity across the entire organisation. Many military medical services have an institutional book that communicate these stories and myths for military medicine. Figure 1 shows some of the books published by military medical services across the globe. Much of military identity is centred around the notion of the ‘military hero’ whose bravery and selfless commitment has led to delivering the mission or saving colleagues. The military medical story is often based on personal heroism at the point of injury followed by technical excellence in the care of casualties through the care pathway.

THE PARADIGM

These domains of the cultural web set the conditions for the organisational Paradigm – the unifying pattern of ideas and beliefs that represent how an organisation behaves to deliver its outputs. In military systems the paradigm might be expressed as a motto, vision, mission or purpose. Examples of published paradigms are shown in Box 1.

Box 1 Examples of Military Medical Paradigms The motto of the British Royal Army Medical Corps – In Arduis Fidelis – Faithful in Adversity The motto of French military medical service – Votre vie, notre combat – your life, our fight. The mission statement of the US Defence Health Agency; the Defense HealthAgency (DHA) is a joint, integrated Combat Support Agency that enables the Army, Navy, and Air Force medical services to provide a medically ready force and ready medical force to Combatant Commands in both peacetime and wartime (8). The role statement of the UK Defence medical services; The primary role of the UK Defence Medical Services is to promote, protect and restore the health of the UK armed forces to ensure that they are ready and medically fit to go where they are required in the UK and throughout the world (9). |

The analysis of the domains of the Cultural Web can be used to determine the alignment between the cultural artefacts of an organisation to its Paradigm; or to determine those cultural artefacts that need to be reviewed if the Paradigm has to change.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper described the strategic challenge for military medical services as: to deliver a garrison health system that delivers military personnel fit for role and, concurrently, to train and operate a deployable medical system that can care for casualties of conflict during deployed military operations. Military medical services operate within a complex cultural environment of military, professional and organisational identities. The paper has described how the ‘Cultural Web’ can be used to analyse the domains of culture within an organisation and to determine its alignment with the organisation’s Paradigm. This method of analysis provides internal value through a process of understanding the cultural environment of an organisation. For a military medical system, it also provides a framework to undertake a comparative analysis with other military medical systems. Most of the challenges for military medical systems are universal and independent of an individual nation – and therefore similarities between military medical systems are likely to be an indication of the route to good solutions. Conversely, differences invite further analysis to confirm that they are appropriate. The paper has also shown the value of the Almanac of Military Medicine and the collective importance of each nations’ entry within it.

References

1. Johnson, G & Scholes, K. (1999). Exploring Corporate Strategy. (5th ed). Prentice Hall.

2. Almanac of Military Corps Worldwide. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/ accessed 15 Apr 2019.

3. Almanac of Military Medicine. Swiss Confederation. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/119-swiss-confederation.html accessed 15 Apr 2019

4. Almanac of Military Medicine. Kingdom of Belgium. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/21-belgium-kingdom-of.html accessed 15 Apr 2019

5. Almanac of Military Medicine. Republic of Singapore. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/111-singapore-republic-of.html accessed 15 Apr 2019

6. Almanac of Military Medicine. Commonwealth of Australia. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/16-australia-commonwealth-of.html accessed 15 Apr 2019

7. Almanac of Military Medicine. State of Israel. Available at: https://military-medicine.com/almanac/66-israel-state-of.html accessed 15 Apr 2019

8. Defence Health Agency. Available at: https://health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency accessed 15 Apr 19.

9. Defence medical Services. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/defence-medical-services accessed 15 Apr 19.

Author:

Lt Gen (Rtd) Professor Martin CM Bricknell CB OStJ PhD DM MBA MA MedSci

Professor of Conflict, Health and Military Medicine

Conflict and Health Research Group

School of Security Studies

King’s College London

Strand Campus

London

Date: 08/13/2019

Source: Lt Gen (Rtd) Professor Martin CM Bricknell CB OStJ PhD DM MBA MA MedSci