Article: H. S. Bhatoe (India)

Neurosurgical Treatment in the Field

Retained Intracranial Splinters: A Review

With rapid evacuation of patients with craniocerebral missile injury (CMI) from the combat zone to neurosurgical centers, early evaluation with computed tomography (CT), improved surgical techniques and post-operative care, there has been an overall improvement in the survival of these patients.

Series have reported improved survivaleven in patients with low Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) (Levy 2000). Thishas also resulted in more survivors with retained intracranialsplinters, who have been followed up over a period of years, andtheir sequelae and outcome have been studied. The veterans with sucha problem may attribute a number of symptoms and problems withretained intracranial splinters. Since the number of personnel withretained intracranial splinters might be rising, there is a need forrenewed awareness of the implications of retained intracranialsplinters amongst the patients, their family members, the primarycare physicians, etc.

Review of the problem

Splinters either with insufficientresidual kinetic energy (KE) to exit the skull or exploding bulletsthat rapidly release their KE get lodged intracranially. Retainedintracranial fragments may be survivors who have not been operatedupon, or those who have retained fragments despite debridement. Thesefragments are generally low velocity missiles such as pieces ofshrapnel, shotgun pellets, secondary missiles or bone fragments.Retained intracranial splinters posed a dilemma for several yearstill their sequelae were understood during the course of follow-upstudies of survivors of various wars.

In Cushing’s experience in World WarI, intracranial infection was the major cause of mortality (Cushing1918). Although he advocated removal of devitalized nervous tissue,Cushing also believed that deeply embedded foreign bodies should notbe removed at the risk of aggravating the neurological damage.However, subsequent military neurosurgeons believed it was imperativeto remove all intracranial bone and metal pieces in a patient withsplinter injury of the brain. Reoperation was advocated if retainedfragments were evident after initial debridement (Hammon 1971,Mathews 1972). One of the primary concerns of such an aggressiveapproach was the fear of infection and formation of inracerebralabscess (Meirowsky 1968). Based on their World War II experience,Martin & Campbell (1946) recorded a parenchymatous infection rate of 16%; they believed that infection was ten times more likelyto occur in the presence of retained bone fragments than in theirabsence.

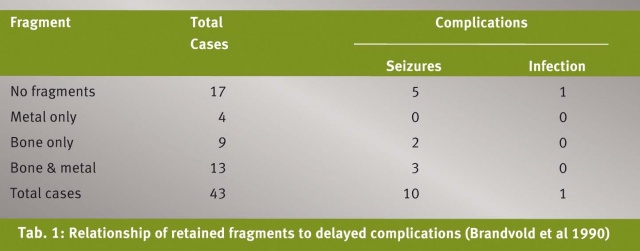

There has been a change in approach,beginning probably from the experience of Brandvold et al (1990) inIsraeli soldiers injured during the Lebanese conflict. With theavailability of CT for immediate evaluation of these patients, a lessaggressive approach was formulated and adhered to, with emphasis onpreservation of cerebral tissue, and removal only of in-drivenfragments that presented themselves on gentle irrigation duringhaemostatic maneuvers. With this less aggressive approach, 60% hadretained metal or bone fragments (or both). The acute outcome withrespect to complications and mortality was similar to that reportedin Vietnam series. No relationship existed between the presence ofeither a seizure disorder or subsequent CNS infection (Table 1).Based on their experience with 379 patients during the Iran-Iraq War,Aarabi (1987) concluded that site of injury and retained splintersdid not have correlation with CNS infection.

Sequelae of retained intracranialsplinters

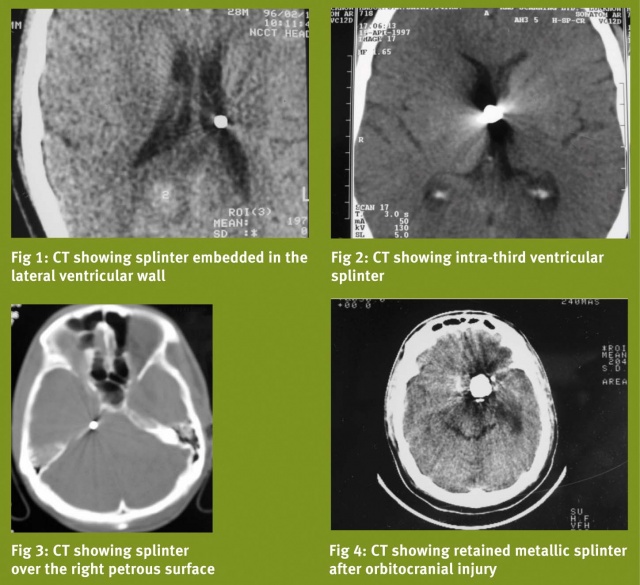

Majority of the retained fragments liedormant, and cause no further problems, although the patients mightattribute a number of non-specific symptoms to these fragments. Wehave seen small fragments lie embedded in the lateral ventricularwall (Fig 1), or in the third ventricle (Fig 2). One patient with asmall retained fragment lying along the petrous ridge on the rightside presented with trigeminal neuralgia, which responded tocarbamazepine (Fig 3). Retained intracranial splinters have beenimplicated in the genesis of the following sequelae:

Infective complications: Splinters thathave transgressed the face, sinuses, orbit and skull base, and thosethat are accompanied by CSF leak, brain matter herniation and brainswelling are the ones that may be followed by repeated episodes ofpyogenic meningitis, ventriculitis, requiring frequent, full courseof appropriate antibiotics. Episodes of meningitis may commencewithin two to three weeks, or may occur after months. These episodesmay be followed by obstructive or communicating hydrocephalus. Brainabscess may form after these episodes of meningitis in the latermonths or years, or they may form during the first few weeks of theinjury. Intraventricular lodgement of the missile predisposes toinfective complications (Clark et al 1986). Entry of the missilethrough the skull vault is less often associated with infectivecomplications (Aarabi 1987, Bhatoe 2001).

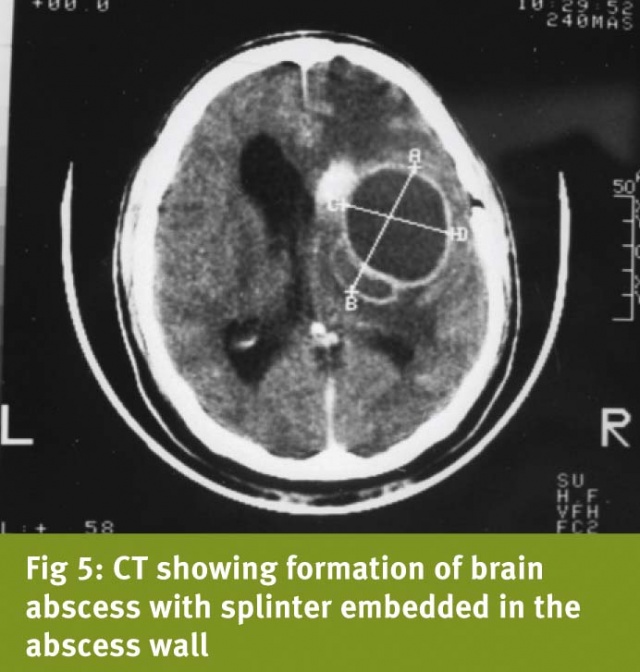

Illustrative case: A 45-year-oldsoldier sustained right orbitocranial splinter injury in 1989, whileserving with the Indian Peace keeping Force. There was no focal motordeficit. His right eye had to be enucleated, and limited debridementof right frontal region was carried out. Metallic splinter could notbe removed. CT brain showed retained metallic intracranial fragment(Fig 4). Over the next four years, he suffered from five bouts ofpyogenic meningitis, each time treated with antibiotics. In 1993, hewas admitted with headache and two-week history of hemiparesis. CTbrain showed thick walled brain abscess with vasogenic cerebraloedema, and metallic splinter adjacent to the abscess (Fig 5). Theabscess was excised together with the splinter. Pus was sterile foraerobes and anaerobes. He showed recovery from hemiparesis over thenext six weeks. However, six months later, he was readmitted withheadache, and this time CT showed hydrocephalus. He underwentventriculoperitoneal shunting and remained asymptomatic thereafter.

Epilepsy: There is no definitecorrelation between occurrence of epilepsy and retained intracranialsplinters (Aarabi et al 2000, Brandvold et al 1990). The pathogenesisof epilepsy after CMI probably involves the formation of anepileptogenic focus, and about one third to one half of the survivorswith CMI can be expected to develop epilepsy.

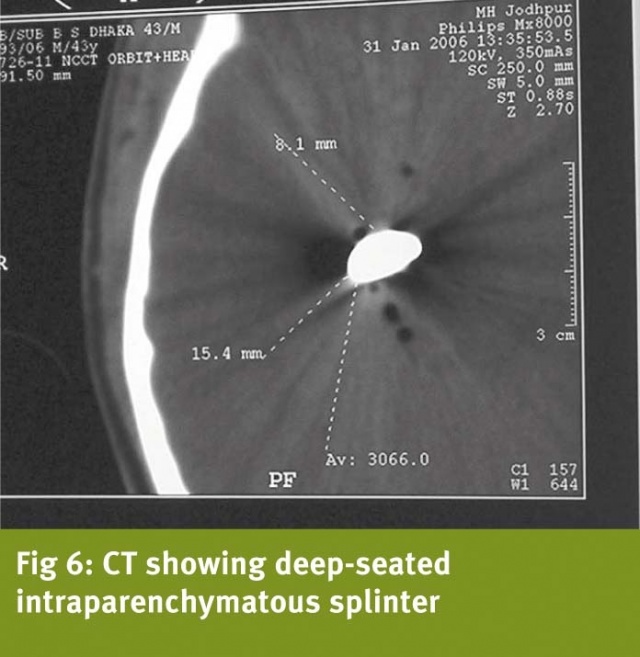

Migration: Besides infection,intracranial migration is of serious concern. A migrating missile canresult in worsening of neurological deficit due to passage of thebullet through the eloquent brain. These fragments may beintraventricular, intraparenchymal or subarachnoid in position. Whenintraventricular in location, these fragments may shift theirposition because of availability of space around them, and have beenimplicated in the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus, ventriculitis,hypothalamic dysfunction, etc. (Dagi & George 1995). Migration isless often seen in intraparenchymal fragments, since they aresurrounded by tissue or gliosis. Migration can occur soon after theinjury along the corridors of tissue damage created by tumbling oryawing passage of bullet through the brain. Movements are aided bybullet weight (heavier bullets tend to shift their position), gravityand brain pulsations and “sink effect” of the ventricles of thebrain (Rengachary et al 1992, Milhorat et al 1993). Delayed migrationindicates softening of the surrounding brain, while arrest ofmigration can occur due to oedema, gliosis and due to the fragmentgetting embedded in a developing brain abscess. Subarachnoidmigration can occur through CSF pathways. Infarction can result fromvascular occlusion (Chapman & McClain 1984). Cerebral aqueductcan get occluded by wandering fragments causing hydrocephalus (Lang1969, Ott et al 1976). Fatal migration into the brainstem has beenreported (Ott et al 1976).

Management Strategy

A retained intracranial splinter is acause for anxiety and concern to the patients and the relatives. Whatis needed is a clear understanding of the nature of the cerebralinjury, and communication with the patients and their relativesexplaining the need for regular follow-up, and close observation forneurological deterioration. While meningitis will be diagnosed andtreated in the usual manner, any fresh neurological event mandatesevaluation by imaging. Brain abscess may require to be excised andoften the missile is found adhered to the abscess wall. There is noaggravation of deficit due to excision of the abscess. Migratingmissile may require appropriate image guided management strategy.Removal can be affected by CT guidance or in case of fragments lyingon the cortex, by taking skull radiographs or intraoperative CT inthe operation theatre to localize them precisely immediately prior toor during craniotomy. Care should be taken to minimize dissection orretraction of brain tissue so as to avoid worsening of neurologicaldeficit.

Date: 02/08/2014

Source: MCIF 1/14