Article: D. Dinger, D. Liebchen, W. Wagner (Germany)

Bladder Injuries in Military Conflicts

The proportion of urogenital injuries during military conflicts is 12.7 %. Bladder trauma occurs in 21.3 % of cases and is often associated with other severe injuries. For diagnostic investigation, a cystoscopy is essential. The treatment of bladder trauma (surgical or conservative) depends on its localisation and on concomitant injuries and follows the guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU).

Introduction

The proportion of urogenital injuries sustained during military conflict is historically reported at around 5 %, however the latest reports put this figure at 12.7 % [1]. Bladder injuries account for up to 21.3 % of these cases and the trend is on the rise. Most urogenital injuries occur as a result of explosions (65.3 - 77 %), penetrating trauma (13 - 14.8 %), blunt trauma (10.6 %) and burns (1.2 %) (see Table 1). Often, traumatic bladder injuries require surgical treatment (47 %) and are associated with pelvic fractures [2]. Patients with gunshot injuries to the lower abdomen, with pelvic fracture, macroscopic haematuria or bladder voiding problems should be investigated for bladder injury. This may have extraperitoneal or peritoneal involvement. The localisation of the bladder injury affects the symptoms, complications and management [3].

Diagnosis

The main symptom of bladder injury is macroscopic haematuria. This occurs in 82 - 95 % of cases, and in around 5 - 15 % of cases only microscopic haematuria is present. Other symptoms include urinary retention, suprapubic impact marks and abdominal guarding where there is an escape of urine into the intra-abdominal cavity. Urine extravasation can also cause swelling of the perineum, scrotum and the anterior abdominal wall. Where there is intraperitoneal bladder rupture, the reabsorption of urea and creatinine can result in uraemia and elevated blood creatinine levels [4].

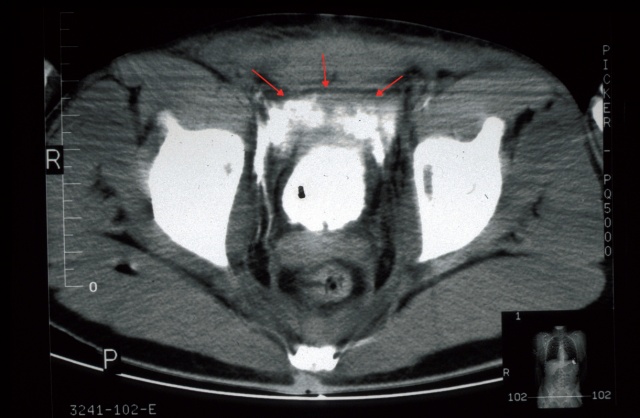

Fig. 1: Extraperitoneal bladder rupture following blunt abdominal trauma with marked ventral extravasation of contrast medium

Fig. 1: Extraperitoneal bladder rupture following blunt abdominal trauma with marked ventral extravasation of contrast medium

Ultrasound and CT investigations can detect free fluid and clot formation in the bladder, however they are not detailed enough on their own to precisely localise the injury. Filling of the bladder with contrast medium during an abdominal CT scan can distinguish between extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal bladder injury (see Fig. 1). In emergency situations, a conventional cystogram has excellent informative merit. Once urethral injury has been ruled out, a plain scan is performed, an anterior-posterior scan and a lateral scan with at least 350 ml of contrast medium being instilled in adults (in children 5 - 7 ml/kg body weight). A scan is taken after the contrast medium has been drained, since this also allows small extraperitoneal extravasations to be detected.

| Since 2001 | Baghdad CSH | Bosnia / Croatia | Vietnam | 2nd World War | |

| Bladder injuries in % | 21.3 | 13.3 | 17.2 | 10.4 | 11.6 |

Table 1: Proportion of bladder injuries among urogenital military injuries; from Serkin et al., 2010 [2].

Treatment

Intraperitoneal injuries, bladder neck injuries and the majority of penetrating injuries require immediate exploration (possibly with further bladder opening), closure in layers with absorbable suture material and the insertion of a suprapubic catheter and perivesicular drainage [3-6]. Bladder injuries with tearing of the anterior abdominal wall, perineum or parts of the bladder wall can, if closure would result in too much tissue tension, be reconstructed using a pedunculated vastus lateralis muscle skin flap plasty [4].

Extraperitoneal bladder injuries frequently result from lacerations caused by bone fragments arising from a pelvic fracture. Most of these injuries heal following the insertion of a trans-urethral catheter within 10-14 days. If the urine is clear, sole catheter insertion is the preferred option. Contraindications to conservative treatment include bone fragments projected into the bladder, open pelvic fracture, rectal perforation and bladder tamponnade. During abdominal exploration due to other injuries, the defect should be sutured and a drain inserted, since this can reduce the risk of infection from osteosynthetic material or perivesicular abscesses. This can also be carried out via a cystostomy in order to avoid decompressing a pelvic haematoma. Both ureteric ostia must be identified if this occurs. If there is concomitant injury to the rectum, a more extensive procedure should be carried out with evacuation of the haematoma and primary bladder closure. After 10- 14 days, a cystogram should be carried out to exclude paravasate and the trans-urethral or suprapubic catheter can then be removed [3-6].

Conclusion

The increasing frequency of urogenital trauma and the associated injuries to the urinary bladder require specific investigation and skilled primary and early care. In the case of explosion-related trauma especially, the possibility of bladder perforation must always be borne in mind, and this should be managed as quickly as possible with urological assessment and treatment. As a result, major pelvic surgery and also reconstructive surgery procedures to treat more complex bladder defects should form an essential part of the urologist's training.

Address of the author:

Major Daniela Dinger

Department of Urology

Hamburg Military Hospital

Lesserstrasse 180

22049 Hamburg

E-mail: [email protected]

Date: 02/21/2015

Source: MCIF 2/15