Report: MCM Bricknell, RF Cordell (UK)

Continuous Improvement in Healthcare Support to Operations

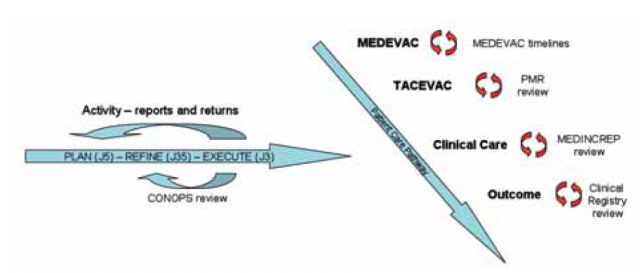

This paper discusses the emerging concept of Continuous Improvement in Healthcare Support to Operations (CIHSO) recently introduced within NATO. It starts by summarising the developments in NATO policy regarding clinical governance and how this has evolved into CIHSO before examining the operational aspects of CIHSO within the Plan-Refine-Execute (PRE) process of operational planning process. It then looks at the components of a CIHSO system as it might apply to the deployed military healthcare system covering the functions of medical and tactical evacuation, deployed hospital care and executing medical operations[h1]. The last stage of PRE should include assessment through the tracking of key performance indicators of the military medical system. The UK and American systems of assurance for the deployed trauma system are reviewed as part of the clinical aspect of CIHSO, as well as consideration some of the emerging issues in the management of CIHSO in a multinational environment.

Introduction

The emerging concept of Continuous Improvement in Healthcare Support to Operations (CIHSO) has recently been introduced within NATO following developments in NATO policy and an evolution from clinical governance as a process to ensure quality in deployed military medical systems. The military medical management component of the CIHSO system can be considered to be the assessment element of the Plan-Refine-Execute (PRE) process of operational planning for deployed military healthcare system. The patient care pathway element utilises information from each of the capabilities of the medical system.

Development of CIHSO

Many assume that the application of principles of clinical governance within military medical services arose from the introduction of the phrase in the landmark paper by Scally and Donaldson.However military medical services have a strong history of sharing best practice and using senior staff as theatre level consultants to observe and monitor standards of medical care. Sir George Makins described the role of the consulting surgeon on the Western Front in the First World War.His most important role was to visit medical units and observe the methods and results achieved at every stage in the medical evacuation system in order to regularise (sic) and bring into conformity the work being carried out throughout the entire army. In World War 2, there were specialist consultants on the staff of the medical branch in the theatre headquarters who performed the same function.Clinical policies were introduced locally and then formalised through the publication of the Field Surgery Pocket Book which survives to this day. The United States introduced the same concept with a Professional Consultants Division being established at the Office of the Surgeon General and in every operational theatre.Clinical practice became standardised through the publication of Technical Bulletin 147 Notes on the Care of Battle Casualties.The UK retained the role of consultant advisers in peace but their role became focussed on maintenance of medical standards in the infrastructure military medical system and training medical specialists for war. Until the 1990s, the military medical system was designed for a short, high intensity war in which capacity rather than capability was the principal driver. The Gulf War in 1990 highlighted the need for a robust field medical record system. The transition from military hospitals to Ministry of Defence Hospital Units aligned military clinical staff with civilian clinical audit practices. Whilst many papers have been published by DMS officers reporting clinical activity on operations and exercises, the absence of a standardised system of data capture and coding has prevented these reported from being used to confirm the validity of the medical plan with activity data.As Clinical Governance was introduced into the National Health Service, the UK Defence Medical Services (DMS) rolled out the same principles into exercises and operations.Both the UK and the US have introduced trauma governance systems that link policies to local practice and systematically evaluate performance of the system through monitoring clinical outcomes. Most recently the performance of the UK DMS was subject to a review by the Healthcare Quality Commission at the request of the UK Surgeon General.This review found examples of exemplary healthcare provision in trauma and rehabilitation services. Since the Gulf War in 1991 operations that UK forces have been engaged in have been supported by multinational medical elements. NATO, as the proponent of multinational support to operations, brought attention to the concept of clinical performance on operations in 1993 by stating ‘the operational standard of care is to be as close as possible to peacetime medical standards’.NATO medical policy and procedures introduced the concept that ‘medical support must meet standards acceptable to all participating nations’.The revision to AJP 4.10 in 2006 amended the standard to ‘achieve outcomes of treatment equating to best medical practice’ and introduced the concepts of Clinical Governance and Evidence

Based Medicine.Experience of multinational operations has shown the necessity to have commonly agreed processes to provide assurance to commanders and the troop contributing nations of the medical support arrangements collectively provided for their forces.The formative NATO Clinical Governance process, known as CIHSO [17], was piloted in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in Afghanistan Regional Command (South) in 2009, before introduction across the ISAF mission later in 2010.

Components of a CIHSO System

Given the inter-relation of all parts of the patient care pathway, it is essential that the application of CIHSO should encompass the whole system of casualty care. CIHSO can be considered to be the final element of the PRE process in medical planning as the assessment of performance of the medical system.There are two components, military medical management and clinical care in the patient care pathway.

Military Medical Management

The effectiveness of the medical plan is monitored through periodic Reports and Returns (R2) that provide feedback on the number and type of casualties who are being managed through the medical system. These will include periodic bed occupancy reports from deployed hospitals, health surveillance reports and medical commanders’ medical assessment reports (MEDASSESSREPs).Taken together, these reports provide information to refine the Casualty Estimate predictions for future military operations, provide a mechanism for review and evaluation of the medical planning process and a continuous assessment of whether medical capacity is adequate or requires modification.

The Concept of Operations (CONOPS) review is the key prospective process for assurance of the medical support plan. As the operational plan is converted into tactical plans, subordinate taskforces submit their tactical CONOPS for review including an assessment of risks and mitigations. The medical support plan is a mandatory element of this submission, which includes a casualty estimate, an assessment of the MEDEVAC requirement and any additional medical support requirements. A pan-headquarters staff team reviews this CONOPS to ensure concurrence with the taskforce assessment and synchronisation with other military activity across the rest of the operational battlespace.

Measuring Performance of the Patient Care Pathway

The most important indicator of performance of the deployed medical system is the clinical outcome for individual patients through the patient care pathway. A considerable volume of organisational and clinical information can be collected in the course of managing the patient care pathway that may inform a CIHSO process. Ideally this would be monitored by means of a longitudinal medical record that follows the patient from point of wounding to definitive care and rehabilitation. Although work is in progress in NATO, building on the experience of the US and UK Trauma Registries and associated processes, such a system does not yet exist in the multinational context. Performance of individual elements of the patient care pathway therefore needs to be assessed separately.

Critical incidents that affect the performance of the medical system should be reported as Event Reports. One format is the Medical Incident Report (MEDINCREP) in use in the ISAF mission in Afghanistan. A MEDINCREP should be initiated by the medical unit concerned in the following circumstances: patients who have died of wounds, unexpected clinical outcome from clinical care, major medical incident, loss of a medical capability (personnel, equipment or infrastructure), a biological or toxicological attack or a bed occupancy of greater than 90 %.The medical unit is required to report the facts of the events and the actions that they are taking in response. This is passed up through the chain of command to the theatre medical adviser with comments from each subordinate headquarters. A complementary report is the Patient Safety Incident Report (PSIR) that is raised by any member of the clinical team who believes they have witnessed an incident in which a patient’s safety has been, or potentially been, put at risk. These are assessed to determine whether remediable action can be taken locally or if ownership of the resource to mitigate this risk is higher up the chain of command.

The performance of the medical evacuation system can be measured by time-based standards derived from medical planning timelines. This has been refined by NATO such that any MEDEVAC mission that exceeds the planning time for MEDEVAC is subject to an “Out-of-Standards” Mission Report. This report contains the facts about the MEDEVAC mission, any reasons for a delay and then an assessment by the receiving medical unit, and critically, the impact of the delay on the clinical outcome for the patient. The same review also applies to TACEVAC missions, although the emphasis for the latter is on ensuring that the skills of those providing in transit care meets the needs of the patient, rather than on time, although timeliness is important.

In ISAF Regional Command (South), oversight and review of the CIHSO process has been achieved through regular Medical Executive Board meetings attended by senior medical leadership of tactical task forces and medical units (including medical evacuation units) under the chairmanship of the regional medical director. This meeting reviews the medical plan, casualty estimate and medical activity to monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of the capacity of the medical system. The meeting also reviews MEDINCREP trends, “out-of-standards” data from MEDEVAC and TACEVAC, and any process issues in the medical evacuation system. Hospital commanders brief on unexpected clinical outcomes and patient safety incident reviews conducted within their facilities.

Issues in CIHSO

Achieving transparency of the internal assurance processes within medical treatment facilities is more sensitive. Not all nations have a culture of clinical review and audit within the S462 medical community. There is sensitivity in some nations over the overlap between clinical review for health quality improvement, managerial review for administrative and disciplinary processes, and legal review for defence against malpractice claims. Finally there is sensitivity to the release of information that would breach confidentiality of the patient and that could cause distress to relatives. On this basis, it was considered inappropriate for NATO to be directly involved in reviews of Patient Safety Incident Reports (PSIRs) within medical facilities. However, it was considered reasonable to expect commanders of multi-national medical units (both units with multi-national staff, or units with multi-national PARs) to provide assurance of their contribution to CIHSO by releasing evidence of procedures, reports of PSIRs and outcomes of internal clinical reviews. One measure of assurance is the demonstration of their medical unit’s contribution to national or international clinical registry systems. Modern information technology has allowed the introduction of clinical case registries and the use of clinical conference calls as a means to share patient data from the entire patient pathway. These innovations have transformed the clinical learning process and allowed the rapid sharing and dissemination of clinical guidelines and best practice.It was also considered appropriate to expect commanders of medical units to fully investigate any concerns over the clinical management of patients at the request of the regional medical director. In essence, the CIHSO process provides a mechanism for sharing examples of best practice, and to learn from difficulties that have emerged in providing medical support on operations, whether systematic, such as communication breakdowns, or shortcomings in clinical care for individual patients, such that the standard for all may continually improve. Risks should be identified through engagement between deployed medical directors and commanders of deployed medical units, and mitigated through finding solutions together. In this way assurance may be provided to commanders, troop contributing nations, the troops themselves and their families, that standards of medical care provided on NATO led operations continue to meet, and indeed, as has been demonstrated, exceed, the standard of healthcare that the individual might expect to receive in their own nation.Central to success is to build and sustain a climate of trust between the managerial and clinical healthcare professionals involved.

Summary

Continuous Improvement in Healthcare Support to Operations has recently been introduced within NATO as an evolution of the role of clinical governance in NATO policy. It has many components, but is best considered as the ultimate facet of the Plan-Refine-Execute process with tracking of key performance indicators of the military medical system.

Note:

This article was first published in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps and is reprinted with the kind permission of the editor of JRAMC

Authors:

Brigadier MCM Bricknell

RF Cordell

Date: 06/20/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (2/2014)