Article: A. HENNINGSEN, W. BERGMANN, K.-O. HENKEL (GERMANY)

Treatment of Bone Fractures in the Facial Rregion - GER Armed Forces Military Hospital Hamburg

The discipline of craniofacial traumatology has developed over thousands of years in response to something that can have fundamentally deleterious effects on the integrity and personality of individuals, namely disfiguring injuries in the facial region.

Introduction

Treatment of fractures has always been one of the main tasks of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. There are even surviving instructions dating back to the 4th century B.C. on how to fix a broken lower jaw to the upper jaw with wire after repositioning. During the First World War, dentists with the appropriate specialist knowledge were called on to deal with the many cases of severe facial and cranial wounds. This gave birth after 1918 to the concept of training physicians in the specific treatment of dental, oral and facial disorders; this was recognised as a separate specialist discipline in Germany in 1935. The demand for maxillofacial and plastic reconstructive surgery grew during and after the Second World War, leading to the development of the corresponding medical facilities throughout Germany.

A female

patient in A&E who

was severely injured

in a road accident.

A female

patient in A&E who

was severely injured

in a road accident.

The frequency of injuries to the head and neck regions, particularly among those involved in military combat, is increasing. Although head, face and neck constitute only some 12% of the exposed surface area of the body, Lew et al. report that 29% of the casualties among the US forces stationed in Iraq and Afghanistan from October 2001 to December 2007 suffered wounds to the head and/or neck, while 27% of these cases involved fractures. This is mainly attributable to the improved protection provided to the thoracic and abdominal regions by body armour. Up to 84% of these injuries were the result of exposure to explosive devices while only 8% were shotgun wounds.

In the case of fractures of bones involved in the oral occlusion process (midface/mandible), there is a primary need to restore occlusion and the necessary treatments should be provided in appropriate specialist oral and maxillofacial surgical departments. However, there are currently no specialist oral and maxillofacial (OMF) surgeons stationed at NATO role 2 and role 3 facilities (rescue centres and field hospitals), meaning that physicians with other specialist qualifications are required to provide provisional corrective measures until such time as the casualties can be evacuated to homeland where they can receive definitive treatment.

Treatment of fractures in the OMF Surgery Department in 2010 - 2012

One of the core tasks of the military hospitals of the German Armed Forces (Bundeswehr) is to provide deployment-relevant training and further education to medical personnel. The purpose of this article is to determine whether the OMF Surgery Department of the Military Hospital Hamburg is covering this requirement by analysing the development of case numbers in the years 2010 - 2012 and the absolute relative proportions of fracture cases.

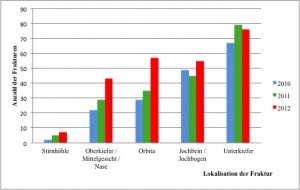

Number of cases of craniofacial fractures in which

surgical revision was provided in the OMF surgery department in

2010 – 2012 by year.

Number of cases of craniofacial fractures in which

surgical revision was provided in the OMF surgery department in

2010 – 2012 by year.

Looking at numbers of cases of treated viscerocranial fractures, it is apparent that there has been a continuous increase in fractures at all sites over the past 3 years. However, it should be borne in mind that the cases documented here are only those in which surgical revision was necessary. Cases in which surgical intervention was not required (e.g. cases of minimally displaced orbital fractures) or in which conservative treatment only was provided (e.g. in the form of intermaxillary lacing) are not included. Similarly, external cases (fracture treatments provided in cooperating hospitals in Hamburg) are not taken into account. The absolute number of fracture cases is thus significantly higher.

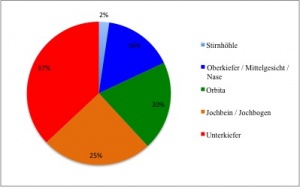

Diagram 2 shows the absolute relative proportions of cases of treated fractures. In more than 33% of all cases, the fracture was located in the lower jaw while in 35% of cases, a fracture of the zygomatic bone or the zygomatic arch required treatment. Although no specific supportive data is available, experience indicates that the complexity of cases has tended to increase over time (in terms of the severity of the injury and also the number of fractures per patient). If a fracture is to be adequately treated, it is essential not only to plan and perform surgery appropriately but also to ensure that there is sufficient pre- and postoperative collaboration between the various disciplines and to provide for management of any resultant complications. Two illustrative cases are outlined in the following.

Case I

Absolute numbers of fracture cases in which

surgical revision was provided in the OMF surgery department in

2010 - 2012 by site of the fracture.

Absolute numbers of fracture cases in which

surgical revision was provided in the OMF surgery department in

2010 - 2012 by site of the fracture.

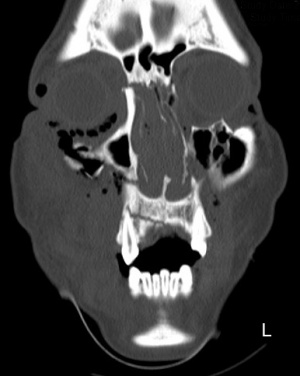

Without breaking, a van collided with a vehicle standing in a tailback on a German motorway. A 20-year old female passenger on the rear seat suffered severe injuries as a result. After being intubated at the accident site, she was transported by rescue helicopter to Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital. Because of continuous haemorrhaging from nose and the midface region, a nasal tamponade was provided in A&E. The subsequent CT scan of the head showed that the bones of the midface of the young patient were extensively shattered. She had bilateral Le Fort I, Le Fort II and Le Fort III fractures together with a sagittal fracture of the maxilla.

After CT, she was transferred directly to the operating theatre. Following stabilisation of the mandible and maxilla using a Schuchardt metal arch/plastic splint, ten osteosynthesis plates (Medartis MODUS Trauma 2.0) were used to reconstruct the midface region while bilateral orbital floor repair was carried out during the operation that lasted a total of 6 hours. On day 1 after surgery, it was possible to transfer the patient from intensive care to a normal ward.

Case II

A 23-year old soldier was referred to the outpatient section of the OMF Department of Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital by a military dentist with pain in the region of the right-sided angle of the mandible.

Midface CT scan, coronal section).

Midface CT scan, coronal section).

It was established that the soldier had been involved in a physical assault some 4 weeks previously during which he had received blows to his lower jaw. During radiographic examination of his injuries following the assault, it was found that he had suffered a double fracture to the mandible (right-sided angle of the mandible and in the left paramedian region), and the patient had undergone osteosynthetic treatment in a civilian hospital on the same day. He had subsequently reported to the treating physician on a weekly basis but the pain in the region of the right mandibular angle had progressively worsened and his occlusion was being displaced. He was only able to eat liquid foods and those with a mush-like consistency.

During clinical examination of the patient, it was observed that the mandibular bone was exposed intraorally and there was a visible fracture gap, local pain on pressure and clear signs of inflammation. There was no occlusion at all in mesial 15/45 and there was severe hypaesthesia in the right lower lip.

Apparent in the orthopantomogram and Clementschitsch view of the mandible were the osteosynthetic repair of a paramedian fracture of the mandible and a fracture of the right-sided mandibular angle. The paramedian fracture was axially aligned. There was an extensive zone of osteolysis in the region of the right mandibular angle while the ends of the fracture were displaced, resulting in significant axial deviation.

We admitted the patient for treatment on the same day and he was given prophylactic antibiotic treatment in the form of an intravenous broad-spectrum penicillin. In order to determine the status of the paramedian fracture, we prepared a model of the patient's maxilla and mandible. It was established that the patient's habitual occlusion could be readily restored in the model. On the next day, under insufflation anaesthesia, Schuchardt splints were first introduced in the patient's maxilla and mandible. The ineffective osteosynthesis plate was removed and osteotomy of the partially ossified and displaced fracture was undertaken. This was accompanied by careful neurolysis and decompression of the contused mandibular nerve. Following intermaxillary fixation and repositioning of the fracture ends, angle-stabilising exclusively intraoral osteosynthesis was provided for by means of the insertion of two osteosynthesis plates (Medartis MODUS Trilock 2.3 and Trauma 2.0). Following release of the intermaxillary fixation, it was possible to readily restore the patient's habitual occlusion. Postoperative radiography showed that the fracture of the right mandibular angle was now axially aligned. On day 1 after surgery, the patient reported a marked alleviation of the hypaesthesia in the right lower lip.

Discussion

Postoperative

occipitomental scan of

the nasal sinuses

following osteosynthesis

using Schuch ardt

internal splinting.

Postoperative

occipitomental scan of

the nasal sinuses

following osteosynthesis

using Schuch ardt

internal splinting.

Treatments of bone and soft tissue injuries in the head and neck regions should always be undertaken in appropriately specialised facilities. Such facilities are the OMF departments of the Bundeswehr hospitals in Hamburg, Koblenz and Ulm. NATO role 4 facilities are able to undertake reconstruction of the highly complex anatomical structures of the head and neck with the aid of 3D imaging techniques. As the point in time at which surgical treatment of fractures is provided is critical in terms of the subsequent outcome, it would be advisable to also provide for specialist OMF treatment options in NATO role 3 facilities.

In Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital, established as a military hospital in 1958, the OMF department was initially created under the supervision of Colonel Dr. Dr. Hammer in 1974. The hospital can now provide state-of-the-art traumatological treatment of injuries in the head/neck region in its modern department that is regularly upgraded to comply with advances in medicine and technology.

In order to ensure appropriate continuous training and further education of the relevant military medical personnel, collaboration with civilian facilities and incorporation in the emergency medical network are essential. The affiliation of the OMF department of Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital with the transregional Hamburg trauma network has resulted in a significant increase in treated cases and also in the admission of more complex cases, a factor that contributes to helping prepare personnel for deployment in the field.

In the article by Lew et al. cited above, it is specified that some 37% of the military casualties wounded while serving in Iraq and Afghanistan suffered mandibular fractures, 19% had maxillary fractures and 11% orbital fractures. While these proportions of mandibular and maxillary fractures are similar to the corresponding proportions among the cases treated by Department VIIb, the number of cases of orbital fractures is almost twice that quoted. This is probably attributable to a large extent to the differing age structure of the relevant patient groups and the mechanisms responsible for the fractures (explosive devices versus falls by older persons whose facial regions are not protected by tactical goggles and helmets).

The patient in

the postoperative

phase 1 week after

implantation of a

plastic nasal splint.

The patient in

the postoperative

phase 1 week after

implantation of a

plastic nasal splint.

As in the case of NATO role 2 and 3 facilities, rapid and targeted therapy requires close cooperation between all relevant medical disciplines, including dentistry. In the case I described above, it was possible to provide rapid surgical revision thanks to the good collaboration between the departments of anaesthesia/emergency medicine and radiology. It is standard practice at the Head Centre of Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital to provide for interdisciplinary trauma therapy through the collaboration of neurosurgery, ENT, ophthalmology and dentistry (Specialist Dental Centre).

Although the management of internally and even externally manifested complications receives relatively little attention when it comes to the treatment of fractures, it does, however, represent a mark of quality. Surgical intervention in order to revise misaligned and healed fractures, as described in case II, is problematic because incomplete healing processes, absorption and infection can result in blurring of the original anatomical structures and outlines. These procedures should be undertaken only after extensive planning and by appropriately qualified surgeons but even then progression to the required outcome is often protracted.

The current techniques of craniofacial fracture repair using osteosynthesis plates are largely based on those developed during the ground-breaking work of the OMF surgeons Luhr and Michelet in 1968 - 1973, which for the first time provided a method of internal fixation. In 1968, Luhr designed the first osteosynthesis compression plate for the lower jaw and thus for the maxillofacial region as a whole. Michelet et al. took a different approach and were the first to repair mandibular fractures with miniplates and monocortically anchored screws, thus making fully intraoral treatments possible. The first clinically practicable system was developed by Champy.

Nowadays, titanium is seen as the material of choice for use in osteosynthesis and reconstruction procedures in the head/neck region. The OMF department of Hamburg Bundeswehr Hospital and the Laboratory of Biomechanics of the Hamburg BG Accident Hospital are currently cooperating in the testing of an innovative angular stable miniplate osteosynthesis system for the treatment of mandibular fractures. At the core of current concepts with regard to new materials are absorbable biomaterials. In the form of polymers and copolymers of lactic acid, bioabsorbable osteosynthesis materials are already commercially available, but these are more difficult to process than titanium and are less stable. The latest research is thus focussing on bioabsorbable osteosynthesis plates and screws made of magnesium-based materials that combine the mechanical advantages of metal plates with the benefits of bioabsorbability.

In conclusion, the rise in numbers of injuries in the head/neck regions means that the Bundeswehr has an increasing requirement for specialist OMF surgeons. Since 2004, this requirement has been covered and will continue to be covered from the ranks of the medical officer cadets, but the main prerequisite was set down with the revision of the German medical officer cadet regulations. The training of these specialists can be a prolonged process thanks to the required dual course of study; at present, the required OMF surgeons are also being recruited from lateral entry career changers.

Contact the author for literature.

Author:

Major MC Dr. Dr. Anders Henningsen

Senior Consultant OMF-Dep Military Hospital Hamburg

Co-Authors:

W. BERGMANN

Colonel MC Prof. Dr. Dr. Kai-Olaf Henkel

Chief of OMF Dep Military Hospital Hamburg

Date: 06/24/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (4/2013)