Article: Hossain Billal, Hasan Zulfikar, Hossain Ismail, Sultana Syeda

Splinter injury to the eye from grenade burst in training ground – our experience of management and recommendation to save valuable eyes

Introduction:

Training of the soldiers is the main component to build an effective strong competent defense forces to combat the enemy. Training ground is a preplanned battle field to exercise the demo of a real war. Even trivial to massive explosive exercise is essential to train our soldiers for future safety of the country from any external or internal threat. Grenade is a very common item in the training field. Any splinter injury from unwanted grenade burst is not expected even safety measures should be enough to practice to save our soldiers from such events. But unfortunately these events cause casualty in training ground which is not very uncommon. It causes huge sufferings of our soldiers and ultimately demoralizes them by losing their organ and confidence. Here we will share our experience regarding management of perforated eye injury from splinter due to grenade burst and we will share our recommendation to save our valuable eyes.

Hand grenades play a very important tools to increase efficiency in military battle field. They can also destroy or disable enemy equipment in any unpleasant situations. So it is very important to handle this grenade carefully and exercise it meticulously to serve the purpose properly. Any mishandling can cause severe casualty.

Methods:

In this retrospective study, hospital records were evaluated from January 2020 to December 2022 to search the patients who were presented with history of injury to eye due to grenade burst in training field. Patient’s demographic data including age, sex were noted. Details regarding injury and its management were noted. Follow up was documented upto at least 6 months of the events.

Results:

Total 9 cases were found. 9 (100%) cases were male and mean age was 26 (23±4 years) years. 7 cases (77.78%) had metallic foreign body inside or outside of eyeball. Most of the cases (55.55%)had stable eyeball but vision was less than LogMar 1.00. 33.33% cases had vision more than LogMar1.00. Phthisis bulbi was developed 2 cases (22.22%). More than two surgery were need in 6 cases (66.67%). Only 1(11.11%) case wore eye protective carbonated glass.

Case Study - 01

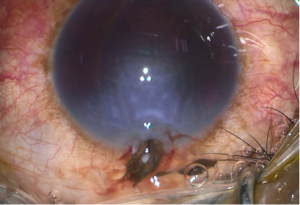

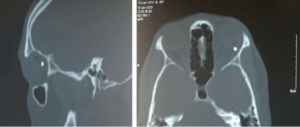

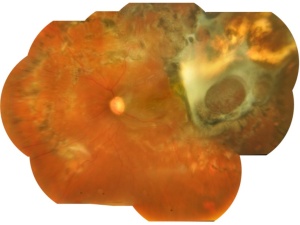

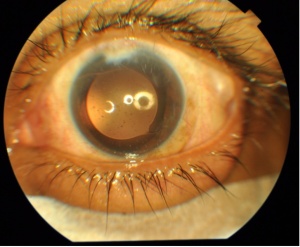

Lt Col AAA1, 38 years old, CO of his unit, was helievacuated to emergency department of Combined Military Hospital, Dhaka with profound loss of vision after splinter injury from grenade burst in training ground. After throwing the grenade, unexpectedly a splinter hit his left eye. There was perception of light vision only. There was a perforating injury with splinter from grenade burst which pierced eyelid, limbus, cornea, lens, vitreous cavity, retina, choroid, and sclera and then situated behind the eyeball [Figure 1]. On CT Scan, there was a metallic foreign body behind the eyeball [Figure 2]. After repair of sclerocorneal wound there was damage of iris, dense hyperemia, disruption of lens capsule, dense vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment and exit wound at temporal to macula. After first surgery patient was remained silicon filled eye without lens. After second surgery by lens implantation, best corrected vision was counting finger with normal intraocular pressure of 14 mm of Hg [Figure 4]. Retina was attached with temporal fibrosis [Figure 3]. Vision was maintained up to three year of follow up. His right eye is absolutely normal.

Meticulous management of perforated ocular injury prevents eye to become phthisis. Even it can provide a good stable valuable vision.

Figure 1- Entry wound of splinter from grenade burst causing damage to the eye.

Figure 2- CT Scan of brain and orbit showing a metallic foreign body is situated behind the eyeball.

Case Study – 02

Snk AAA2, 24 years old soldier, injured with splinter of grenade burst due to unintentional exploration. His right eye was only involved with splinter, which entered his eye piercing sclera, iris, lens and, metallic parts were rest at vitreous cavity. Those foreign bodies were removed by vitreo-retinal surgical procedure. Now his eye is maintaining only contour with silicon oil inside. Soon we will implant artificial lens after removing silicon oil. But already there is mild decompensation of cornea due to silicon effect, so ultimate prognosis is very guarded.

Case study – 03

LCpl AAA3, 27 years old soldier, got splinter injury in his eye from grenade burst in their training ground. His colleagues were also injured, though those were non-ocular casualty. Splinter enters his eye by perforating his eyelid, sclera, lens, vitreous cavity, retina, choroid, and sclera and enters to cranial cavity. Ultimately he was diagnosed as a case of perforated ocular injury with retained intracranial metallic foreign body. In spite of aggressive treatment, he developed endophthalmitis which was subsequently managed with vitreo-retinal surgery. Now eyeball has been settled. But due to massivedamage in all Zone I, Zone II and Zone III, visual improvement is uncertain1.

Effects of ocular splinter injury due to Grenade burst:

Ocular trauma is the fourth most common injury sustained in military combat today. In a pool of 387 randomly selected soldiers injured by blast trauma in Operation Iraqi Freedom, 329 (89%) sustained ocular trauma1,2,3. Emergency treatment of resulting injuries falls under the realm of emergency care and effective patient triage, often incorporating protocols for blunt and penetrating trauma. As a result, physicians have devised a concise algorithm for the treatment of patients with ocular injuries secondary to blast trauma3. Ocular trauma may result from primary blast exposure. Primary blast ocular trauma therefore comprises non-penetrating mechanical injuries such as hyphemas, ruptured globes, conjunctival hemorrhage, commotio retinae and orbital fracture4,5. Secondary blast ocular trauma is distinguished by penetrating or blunt force injury to any of structural component of the eye or orbital; open globe injuries, adnexal lacerations of the lacrimal system, eyelids and eyebrows comprise the majority of injuries in this group3,4.

Recovery of vision after perforating trauma:

Visual outcomes for patients with ocular trauma due to blast injuries vary, and prognosis depends upon the type of injury sustained. The majority of poor visual outcomes arise from perforating injuries: only 21% of patients with perforating injuries with pre-operative light perception had a final best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) better than 20/200. Collectively, patients who experienced choroidal hemorrhage, perforated or penetrated globes, retinal detachment, traumatic optic neuropathy, and subretinal macular hemorrhage carried the highest incidence rates of BCVAs worse than 20/200. Reports from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) indicate that 42% of soldiers with globe injuries of any kind had a BCVA greater than or equal to 20/40 six months after injury, and soldiers with intraocular foreign bodies (IOFBs) retained 20/40 or better vision in 52% of studied cases1,2,3.

Figure 4- Composite mosaic picture of whole inner part of eye – retina, the light sensitive area of visual stimulation capturing system after repair of perforated ocular injury with retained intraorbital metallic foreign body from splinter injury due to grenade burst in training ground. (Side picture is normal eye to compare)

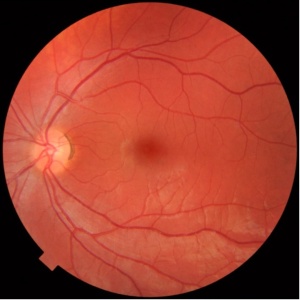

Figure 5- Central effective position of artificial intraocular lens after repair of perforated ocular injury with lens damage from splinter injury due to grenade burst.

Globe perforation, oculoplastic intervention, and neuro-ophthalmic injuries contribute significantly to reported poor visual outcomes. 21% of tertiary centers treating patients exposed to blast trauma reported traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) in their patients, although avulsion of the optic nerve and TON were reported in only 3% of combat injuries2. In the event that a victim of globe penetrating trauma cannot perceive any light within two weeks of surgical intervention, the ophthalmologist may choose to enucleate as a preventative measure against sympathetic ophthalmia.

Discussion:

Splinter related perforated ocular injury is not uncommon in the world. This may happen in real battle field and in training ground also. Any perforated ocular injury deserves meticulous handling and proper composite decision about further intervention. A proper preplanned effective surgery may give stability to ocular contour, even there may be chance of visual recovery also.

Gundogan FC et all described a study in which total of 139 casualties were transferred to the regional military hospitals, of which 48 (34.5%) had ocular injuries and it is the 83 injured eyes of these 48 male casualties that form the subject of that study6. The mean age was 24.5±6.6 years (range 20–45 years). Right, left and bilateral eye injuries were observed in 7 (14.6%), 6 (12.5%) and 35 (72.9%) patients, respectively. All of these soldiers were wearing body armour at the time of the explosion but none were wearing combat eye protection (CEP).

Thomas et all reported a decrease in ocular injuries from 26% to17% when CEP was worn and those injured while wearing CEP had less severe injuries; they also reported a 16% increase in CEP use compliance after an intense ocular protection education programme4. It has been reported that 42% of the eye injuries sustained in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars could likely have been prevented by the use of CEP In the Iraq War, only 9.3% of the casualties were wearing CEP at the time of injury7. The high percentages of bilateral eye injuries detailed both here and in the literature highlight the importance of CEP. None of the casualties in their study were wearing CEP, although all of them had been issued CEP. This finding also highlights the importance of ocular protection education programs for military personnel because such programs have been shown to increase CEP compliance.

Protective tips in field for handling grenade:

Before employing hand grenades or when in areas where they are in use—

- Inspect all grenades for service ability before use.

- DO NOT remove the safety clip or the safety pin until the grenade is about to be thrown.

- In response to a dropped grenade, Soldiers must move immediately from the danger area and drop to the prone position with the Kevlar helmet facing the direction of the grenade.

Recommendations for eye protection:

- Ocular blast injuries due to explosive military ammunition cause severe visual loss.

- Combat eye protection is a key factor in reducing the frequency of ocular involvement

- The soldiers should be educated through eye protection education programs.

Conclusions:

Ocular blast injuries cause severe visual loss irrespective of the explosive munitions which may be in the battle field even in the training ground. Wearing of combat eye protection device will reduce the blinding ocular casualty and will keep our soldiers safe, confident and morally high. Military personnel should be educated through eye protection programs about the use of combat eye protection device.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: Nil financial disclosures even no public private support.

Statement of Ethics: This study complied with the tenets of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Combined Military Hospital Dhaka (approval number: 23.01.901.093.06.199.01.19.02.24). The requirement of obtaining informed consent from study participants was waived by the IRB given the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References:

- Ramasamy A, Harrisson SE, Clasper JC, Stewart MP., Injuries from roadside improvised explosive devices. J Trauma 2008; 65(4):910-4.

- Weichel ED, Coyler MH. Combat ocular trauma and systemic injury. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2008; 19(6):519-25.

- Wolf SJ, Bebarta MV, Bonnet CJ. Blast injuries. Lancet 2009; 374(9687):405-15.

- Thomas R, McManus JG, Johnson A, Mayer P, Wade C, Holcomb JB. Ocular injury reduction from ocular protection use in current combat operations. J Trauma. 2009. 66(4):S99-S103.

- Chavko M, Watanabe T, Adeeb S, Lankasky J, Ahlers ST, McCarron RM. Relationship between orientation to a blast and pressure wave propagation inside the rat brain. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010. 30(1):61-66.

- Gundogan FC, Akay F, Yolcu U, et al. J R Army Med Corps Published Online First: [ please include Day Month Year] doi:10.1136/jramc-2015- 000408

- Ari AB. Eye injuries on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan: public health implications. Optometry 2006;77:329–39.

- AIN 106-10, Ammunition Information Notice (M116A1/M115A2), 11 August 2010. https://www.us.army.mil/suite/doc/27601902

- ATTP 3-06.11 (FM 3-06.11), Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain, 10 June 2011. https://armypubs.us.army.mil/doctrine/DR_pubs/dr_aa/pdf/attp3_06x11.pdf

Date: 05/08/2024