Article: Klemmer, Frank; Kyle, Stigall; Michael, Hetzler; Samuel A., Rocker; Griet, Vermeulen;

Minimum Requirements for the Interoperability of Special Operations Surgical Teams: An Assessment Based on Current National Standards and NATO Doctrines

Abstract

Background

To reduce mortality and morbidity in combat situations, a Special Operations Surgical Team (SOST) should be positioned close to the point of injury (POI). SOST capabilities include both damage control resuscitation (DCR) and damage control surgery (DCS) performed by specially trained medical professionals. The modern battlefield requires mobile, lightweight, scalable, modular, and flexible surgical capabilities like SOST to meet established casualty care timelines in medical support of Special Operations Forces. There is currently a shortage of SOSTs capable of DCS and DCR, which must be addressed through the establishment of minimum requirements at the NATO level via the development ofnational medical standards and targeted training programs.

Method

To establish the minimum requirements for interoperability, a mixed-methods approach was utilized. The Bundeswehr's Medical Service hosted the SOST international working group in Munich in September 2024, where 72 participants from 13 nations and 15 Special Operations Surgical Units were organized into 4 syndicates. Discussion within the syndicates focused on Selection and Training, SOST Platforms and Configurations, DCR and DCS capabilities, and SOST Evaluation Methods. Following the workshop, feedback was solicited from Subject Matter Experts (SME) representing all 13 nations regarding team configuration, platform variants, and SOST skills. The process ensured a comprehensive understanding of interoperability and minimum requirements through both quantitative and qualitative (Delphi-Method) methods. Additionally, literature research was conducted in NATO documents to highlight previously established guidelines.

Results

The analysis of 15 quantitative responses (15 questions within the syndicates) and 39 qualitative responses (from each nation) regarding Selection and Training, SOST Platforms and Configurations, DCR and DCS capabilities, and SOST Evaluation Methods resulted in insights that highlighted commonalities among the nations. Minimum requirements for working in the international environment of NATO have been identified and listed as prerequisites.

Conclusion

The shared insights among nations and syndicates regarding Selection and Training, SOST Platforms and Configurations, DCR and DCS capabilities, and SOST Evaluation Methods indicate that foundational data for establishing minimum NATO requirements is available. The data shows a wide variance in SOF medical capabilities across multiple NATO countries supporting the need for formalized NATO doctrine focused on a standardized approach to medical interoperability.

BACKGROUND

The importance and necessity of maintaining a Special Operations Surgical Team (SOST) within the evacuation chain in special operations is supported by multiple NATO doctrine and directives. However, the minimum medical requirements, the technical implementation of platforms and the composition of teams have not yet been established. Furthermore, interoperability among NATO member nations regarding SOST capabilities has not been specified, leading to discrepancies in deployability and effectiveness. The current and future operational environment will require mobile, lightweight, scalable, modular, and flexible surgical capabilities to meet doctrinally accepted casualty care timelines. (Tägerwilen II Report, Transfusion 2024)

To reduce mortality and morbidity in combat situations, it is essential to position SOSTs close to the point of injury (POI). SOSTs provide critical capabilities in damage control resuscitation (DCR) and damage control surgery (DCS), delivered by medical professionals who have undergone selection and specialized training. The requirements of the modern battlefield necessitate skills that traditionally trained medical providers do not receive. These skills include both tactical and medical knowledge. Without adequate training and selection of team members, SOST personnel can become a hindrance to the mission, rather than a tool to mitigate risk and save lives.

Despite their importance, there is currently a shortage of SOSTs capable of providing DCS and DCR for Special Operation Forces (SOF). This deficiency must be addressed through the establishment of minimum requirements at the NATO level, which can be achieved by developing national medical standards and targeted training programs.

The contemporary operational environment is characterized by rapid changes and an increased operational tempo, further underscoring the need for effective and responsive medical support. These features will enable SOSTs to provide immediate assistance in high-stress and hazardous environments with varying operational demands.

Through the use of SOST, SOF Commanders gain several advantages, such as increasing operational reach, reducing risk, ensuring troop welfare, bridging gaps in medical care, and supporting political mitigation.

Currently, the evaluation and validation of SOSTs are hindered by the limitations of NATO‘s evaluation doctrine, which only begins at Role 2 Basic (R2B). There are no parameters to evaluate and validate SOSTs and they do not fit well into the Role 2 Medical Treatment Facility (MTF) echelon due to the high mobility and limited holding capacity they provide. This gap has contributed to a significant deficit in the establishment and operational readiness of SOSTs within NATO.

The lack of comprehensive guidelines and minimum requirements hinders uniformity in SOST configurations, leading to significant diversity in team compositions and specialized training programs that are difficult to compare due to differing standards and educational pathways. Additionally, team sizes within SOSTs range from 3 to 10 members based on the operational context, which complicates coordination and integration among allied forces and can undermine the effectiveness of medical interventions in combat situations. This variability poses a challenge to NATO‘s medical interoperability and flexibility.

AIM

The objective of this workshop in Munich 2024 was to enhance the understanding of DCR and DCS within the initial surgical care of the evacuation chain for SOF through the SOST. This initiative was conducted in a comprehensive manner for the first time within NATO. Additionally, the workshop aimed to emphasize the importance of specialized training tailored to the evolving challenges faced by NATO SOF forces. The workshop sought to establish a foundation for assessing the current capabilities of individual nations to facilitate discussions aimed at creating a coherent, knowledgeable, and agile medical SOST that is adequately equipped and trained to address the complexities of modern warfare within the principles of NATO SOF operations. Finally, the event served as a platform for networking within the NATO SOST), fostering collaboration and interoperability among allied medical and surgical units.

METHOD

The Bundeswehr Medical Service hosted the SOST international working group in Munich in September 2024 with the participation of 72 delegates from 13 nations and 15 Special Operations Surgical Units. They were divided into four syndicates to discuss the four key themes that needed to be analyzed for minimum interoperability requirements.

The four key themes were:

1. DCS and DCR capabilities;

2. Selection and training;

3. SOST platforms and configurations; and

4. SOST evaluation methods.

The workshop participants from a nation were assigned to different syndicates in order to minimize the influence of group pressure (national opinion) and the dominance of individual persons (superiors).

Following the workshop, the results of each syndicate were summarized and sent to Subject Matter Experts (SME) representing all 13 nations asking for analysis and review with regard to team configuration, platform variants, and SOST skills (Modified Delphi Method).

The Modified Delphi Method is a structured communication technique for consensus building among experts. It is based on anonymous surveys to minimize peer pressure and takes place in multiple rounds, during which participants receive the results of the previous round to adjust their opinions. This promotes a convergence towards consensus. The method is often used in health research, as it provides both qualitative and quantitative data and systematically analyzes divergent opinions.

The process ensured a comprehensive understanding of interoperability and minimum requirements through both quantitative and qualitative methods. Additionally, literature research was conducted in NATO documents to highlight previously established guidelines.

The key themes were used as a basis during the workshops, where 15 SOST (or similar representatives) from 13 nations answered a total of 17 questions. During the syndicate work, a combination of standardized questions, focus group surveys, and a modified Delphi method was employed. A consensus of ≥90% was reached for 14 statements. In parallel, responses were requested by having the SME fill out an Excel sheet with identical topics. Responses with an average score of >90% were included in the following investigations of commonalities and interoperability.

Figure 1. Procedure and Implementation of the Modified Delphi Method

Figure 2: Participants of the SOST International Working Group 2024 (source: authors)

Results – Commonalities and interoperability

The analysis of 15 quantitative responses (15 questions within the syndicates) and 39 qualitative responses (from each nation) regarding Selection and Training, SOST Platforms and Configurations, DCR and DCS capabilities, and SOST Evaluation Methods resulted in insights that highlighted commonalities among the nations. Minimum requirements for working in the international environment of NATO have been identified and listed as prerequisites. The following results were generated from the workshop.

DCS and DCR capabilities

SOST must be able to provide DCR, DCS including laparotomy/thoracotomy, field anesthesia, amputation completion, and vascular shunting. These results are consistent with the guidelines of the NATO Special Operations Medical Leaders Handbook (2016). Through the training institution of the NATO Allied SOF Command – the University College Cork (UCC) – the following essential skills are taught and defined as minimum prerequisites: laparotomy for controlling bleeding and intestinal spillage; thoracotomy for penetrating chest injuries/ clamping; resolution of cardiac tamponade; temporary restoration of blood flow to a limb using vascular shunts; external fixation of fractures; amputation of mangled limbs; fasciotomy; decompressive craniotomy (+/-). The current version of the Handbook (2024) was not considered here, as it does not reflect the SOST requirements but rather aligns more with a conventional Role 2 Forward (R2F) approach. To list some differences, the SOST has only limited patient holding capacity, limited resupply, and no prescribed structural configuration due to platform independence. Additionally, unlike conventional R2F, SOST can be deployed in land, air, and sea domains due to their material, training, and platform independence.

Through the survey of the international SME SOST, the following skills and capabilities were identified as common denominators for all nations. Out of 49 selected skills and competencies, 17 shared a commonality among all SOST.

Table 1. Common Denominators for all Nations.

(Resuscitative) thoracotomy | invasive blood pressure (IBP) |

Airway video | Infraclavicular exposure |

Amputation | Large bore central line |

Ultrasound | Neck exploration |

Basic monitoring (SpO2, ECG, NIBP) | Pelvic packing |

General anesthesia | Pelvic splinting |

Clamshell thoracotomy | Sternotomy (subclavian bleeding) |

Clavicular exposure | Telemedicine |

etCO2 Monitoring |

Table 1: Common denominators checklist for all Nations (source: SOST International Working Group 2024)

Selection and Training

Requirements for Training and Education by NATO Doctrine: For interoperability, a minimum of Language Proficiency Level (LEVEL 2) in English with specialized training in medical English is required. Due to the operational environment of SOST, a classification into the training level of survival, evasion, resistance, extraction (SERE) at LEVEL Bravo is required.

Figure 3: Light Utility Helicopter – SOF configured as a Special Operations Critical Care Evacuation Team (SOCCET) following surgery (source: authors)

Selection: SOST personnel is selected based on their physical and mental fitness, medical competence, psychological profile and mindset, as well as their adaptability to the tactical environment of the SOF.

Training: The foundation for the tactical training of SOST must be defined by the national SOF, and the content must be conveyed in the basic SOST training. Additional training in Special Operations Medical Planning and Support should be integrated into the program.

Currently, there are only two official training programs for SOST, which are offered by the United States Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) and the NATO Allied SOF Command in conjunction with the UCC.

An interesting aspect here was the national necessity in training courses such as diving medicine, altitude medicine, parachuting, fast roping, and tropical medicine. This was only sporadically supported by nations as required training. However, it raises the discussion point of which training courses should be considered minimum requirements for a NATO SOST.

The summarized training content must continuously be practiced as small unit tactics in large-scale military operations at the national SOF level and within the NATO SOF environment.

Key Requirements Due to the increased implementation of minimally invasive procedures and computer-assisted surgeries, a national system must be established to ensure training for wartime surgery, as most clinics in Europe cannot achieve the case numbers for gunshot and stab wounds like the extensive civilian trauma network within the United States or specific hospitals such as Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, South Africa.

Figure 4: SOST in ‘safe house’ conditions (source: authors)

Platforms and Configurations

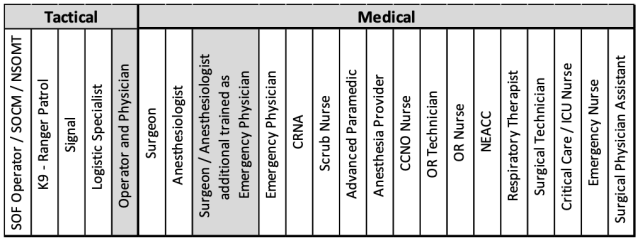

Configurations: The team configuration of a SOST for establishing a surgical workspace (1 patient at a time) consists of 6 individuals for 90% of respondents or can be reduced to 6 individuals due to team size. A fixed assignment of specific job descriptions is not possible, as 20 different training pathways and levels of qualification have been described. The areas represented in gray show the dual function, tactical and medical, as well as the dual training as a special feature in the SOST.

Table 2. Training pathways and levels of qualification

Table 2. Training pathways and levels of qualification

Table 2. Training pathways and levels of qualification

PLATFORMS: SOST must be able to reach the operational area on foot and be deployable on platforms such as van, truck, tent, house, and ship. These options of the platforms have been confirmed by 13 SOST or comparable surgical elements and are already implementable by the nations. The rotary wing and fixed wing variants must be implemented; however, there is a lack of approval for the SOST systems from the aviation safety authorities of the countries, which affects interoperability. Deployment on aircraft must be authorized repeatedly by the responsible military authorities and cannot be generally planned as a standard size.

Figure 5: Mobile SOST in a ‘van configuration’ (source: authors)

SOST Evaluation

As a working basis, the following documents and doctrines were summarized: the Law of Armed Conflict (ICRC), STANAG 6001 – Language Proficiency Levels, AMedP-1.8 Skill Matrix, AMedP-1.6 Medical Evaluation Manual, Medical SOF Evaluation (SOFCOM), and AMedP-4.13 NATO Special Operations Forces Medical Support.

The individual requirements were discussed and evaluated. The two main statements were:

- An evaluation form provided by SOFCOM is necessary to define the minimum requirements for NATO SOST.

- The SOF Evaluation must be close to the evaluations of conventional medical treatment facilities in the areas of DCR and DCS.

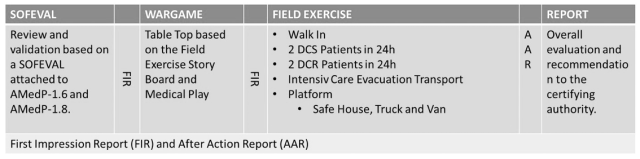

It is imperative that, following an evaluation, a validation process must be conducted according to standardized qualitative and quantitative parameters. This could be implemented according to the framework presented in Table 3.

The process outlined in the table is based on the principles of the NATO International Military Medical Observer and Trainer Course and the International Military Medical Evaluator Course.

Figure 2. Self-Assessment and Main Questions / AMedP-1.6 Medical Evaluation Manualviii ix

Figure 3. Summary from the AMedP-1.8 / Skills Matrix (NSO, 2016)x

Figure 4. Summary from the AMedP-1.8 / Skills Matrix (NSO, 2016)

Figure 5. Minimum Test Requirementsxi

• The evaluation / validation must not be limited to paperwork but must also be conducted through practical implementation/exercises.

Table 3. Possible theoretical and practical SOST SOF Evaluation / Validation

The process outlined in the table is based on the principles of the NATO Course International Military Medical Observer and Trainer Course and the International Military Medical Evaluator Course.

CONCLUSION

The collective insights from various nations and syndicates concerning Selection and Training, SOST, Platforms and Configurations, DCR and DCS capabilities, as well as SOST Evaluation Methods, reveal that foundational data for establishing minimum NATO requirements is accessible. Analysis of this data highlights considerable variability in SOF medical capabilities across NATO Member States, underscoring the necessity for formalized NATO doctrine. Such doctrine should emphasize a standardized framework for medical interoperability. The existence of foundational data signifies that NATO possesses the information needed to create comprehensive requirements, ultimately facilitating improved collaboration among member nations. By establishing a unified approach to medical interoperability, NATO can enhance operational efficiency and responsiveness, ensuring that SOF units are adequately supported regardless of their national origins. This standardization is vital in optimizing mission outcomes and maintaining a cohesive operational strategy among diverse NATO forces engaged in complex and dynamic environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All members of the SOST Working Group (Munich) and the national Subject Matters Experts SOST are acknowledged for their contribution to these recommendations.

REFERENCES

i Christian Medby, Colleen Forestier, Benjamin Ingram, et al: The Tägerwilen II report: Recommendations from the NATO Prehospital Care Improvement Initiative Task Force, 3.3 Forward surgical capabilities, Transfusion, February 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.17760

ii JOINT TRAUMA SYSTEM CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE (JTS CPG), Austere Resuscitative and Surgical Care (ARSC) (CPG ID:76), October 2019

iii NSHQ: NATO SPECIAL OPERATIONS MEDICAL LEADERS HANDBOOK, Chapter 8, June 2016

iv NSHQ, NATO Special Operations Surgical Team Development Course, SOF-SO-31925, https://www.nshq.nato.int/Training/EventDetails/8bfee223-95e7-1b4a-6f4c-46eaaa9dc65a [02.12.2024]

v NSHQ: NATO SPECIAL OPERATIONS MEDICAL LEADERS HANDBOOK, 2024

vi NSO: NATO STANDARD ATrainP-5 LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY LEVELS, May 2016

vii SHAPE Europe: ACO DIRECTIVE 080-101 PERSONNEL RECOVERY IN NATO OPERATIONS, April 2015

viii NSO: NATO STANDARD AMedP-1.6 Medical Evaluation Manual, September 2018

ix International Humanitarian Law Databases: Geneva Conventions, Article 40 (2), 2016

x NSO: NATO STANDARD AMedP-1.8 Skills Matrix, January 2016

xi NSO: NATO STANDARD AMedP-8.5 MINIMUM TEST REQUIREMENTS FOR LABORATORY UNITS OF IN THEATRE MILITARY MEDICAL TREATMENT FACILITIES (MTFs), June 2023

Date: 07/25/2025

Source: OLt KLEMMER, Frank, [email protected] November 2024