Report: A. Spiegel (Germany)

Neurosurgical Emergency on the Frigate Bremen

A Case of life-threatening symptoms of intracranial pressure in a saylor onboard the frigate Bremen deployed in the Indian Ocean

Introduction

EU NAVFOR Somalia – Operation Atalanta is a multinational mission of the EU that has the objectives of protecting the humanitarian aid services being provided to Somalia, of securing the local sea routes and of suppressing piracy along the coast of Somalia, around the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden. A combined multinational flotilla has been put together to achieve these tasks. This is the first naval mission undertaken by the EU. The contingent supplied by the German Navy is represented by a frigate, two ship-based helicopters and a boarding team.

The ship has an on-board ship’s surgeon to provide for the healthcare of the crew. In view of the considerable distance from the homeland and the expected intensity of the operations, also deployed on the ship is a so-called ‘on-board medical specialist team’ (Bordfacharztgruppe), consisting of a specialist anaesthetist, a specialist surgeon and a specialist dentist. In addition to the general medical care provided by the ship’s surgeon, provision has mainly been made for the treatment of injuries sustained as a result of accident or combat. The surgical materials and equipment available are thus mainly designed for use in the treatment of wounds, bone fractures and damage control surgery (1). This includes the trepanation instruments required to relieve traumatic epi- or subdural haematomas. The necessary skills to carry out such operations are part of the expertise learnt by general surgeons during their training.

On 9 August 2012 in Djibouti, the frigate Bremen was relieved by the frigate Sachsen, which was to assume the former’s duties within Operation Atalanta. At this point in time, Bremen’s on-board helicopter with its aircrew was already on its way to Germany. Before Bremen could embark on its voyage home to Wilhelmshaven, it was to visit Mumbai Harbour as part of the celebrations of the “Year of Germany and India” intended to the mark 60 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

During the crossing to India on 14 August 2012, a member of the crew on board the frigate Bremen developed a life-threatening disorder that became so serious that evacuation of the patient by air and emergency surgery on the Indian Navy Hospital Ship Asvini in Mumbai became necessary.

The case

The case

Medical background

During the evening of 13 August 2012 at about 6.00 pm, the ship’s surgeon was called to a case in which a member of crew had began vomiting and had collapsed as a result of extremely severe head pains. The surgeon was already aware of the case and suspected that the crew member was a migraine sufferer. On arrival of the surgeon, the patient was alert and adequately orientated, his cardiovascular status was stable and there were no neurological deficits. The patient had not fallen and there were no visible external injuries. The patient was able to walk unaided to the ship’s sick bay for further treatment and here he was kept under observation overnight.

He was given antiemetics in the form of metoclopramide, diphenhydramine and dexamethasone and also paracetamol and 3 mg piritramide in divided doses during the night for analgesia. Following situation-adapted infusion of a total volume of 1500 crystalloid solution, adequate diuresis was observed. The patient was subsequently monitored by the anaesthesia sergeant who had training in intensive care medicine.

At 8.00 am on 14 August, the patient was reassessed and the situation reviewed. Despite the provision of adequate analgesia, the patient had experienced no alleviation of the pain localized in the frontal cranial region and had repeatedly vomited during the night although antiemetic therapy was continued. The general status of the patient was by now poor; he was somewhat somnolent and suffering from severe pain. However, it was still not possible to identify any specific neurological problems. The results of testing of his motor abilities and sensory capacity were normal. There was no stiffness of the neck and the pupils on both sides were uniformly narrow and sensitive to light stimulus. At the same time, there was slightly abnormal bradycardia (40 – 50/min.).

In consultation with the ship’s surgeon, the decision was made to subject the patient to more detailed diagnostic procedures as rapidly as possible. The closest port at this time was Mumbai in India, which was still 370 nautical miles away. At its maximum speed (approx. 27 knots), the ship would require 14 hours to reach Mumbai.

Shortly after the patient had been examined, he suffered a generalised seizure with a maximum duration of 60 seconds; this spontaneously ceased on i.v. administration of 10 mg diazepam. The patient was now exhibiting the characteristic symptoms of a postictal state, with impaired vigilance and suppressed spontaneous respiration, although cardiovascular status and blood pressure were normal (Riva-Rocci: 120/70 mm Hg). Pupils were on both sides moderately dilated, exhibited isocoria and were sensitive to light.

Initial therapy

Assuming as a working diagnosis the presence of an unidentified intracranial lesion (such as a tumour), the patient was also given 50 mg dexamethasone. The results of the laboratory tests that it was possible to perform onboard indicated no relevant abnormalities. It was not possible to further examine the patient using imaging techniques as the relevant equipment was not available on the ship.

In view of the lack of space in the sick bay, the poor status and somnolence of the patient and the recurrent vomiting, the decision was made to electively intubate the patient (patient protection, prevention of aspiration, reduction of intracranial pressure).

At around 9.15 am, elective anaesthesia was induced and an endotracheal tube was introduced without problems. General anaesthesia was maintained using propofol and fentanyl and gradually increased. In order to prevent the risk of a cerebral seizure under anaesthesia, intermittent bolus doses of diazepam were administered. Administration of norepinephrine (1 µg/min) had been commenced on induction of anaesthesia in order to maintain cardiovascular function and control cerebral perfusion pressure, but by this time was found to be no longer necessary. The cardiovascular status of the patient was largely stable and regular checks of pupils showed these to be bilaterally narrow and slowly reactive. At around 1.00 pm, a further 10 mg diazepam was administered and anaesthesia was maintained using 600 mg/h propofol and 300 µg/h fentanyl. At this point in time, both pupils were not dilated.

At around 1.10 pm, both pupils suddenly exhibited maximum dilation and ceased to be sensitive to light although both blood pressure and heart rate showed little change. Anaesthesia was immediately deepened, and 500 mg thiopental and an additional 50 mg dexamethasone were given. No mannitol was available and the administration of HyperHaes (hypertonic 7.2 % saline solution with 6 % HES) was considered, but not actually initiated. Ventilation was adjusted to 100% oxygen with hyperventilation at an ETCO2 of 25 mm Hg. In consultation with the specialist surgeon (who was now present), a trepanation procedure in order to relieve intracranial pressure was discussed and the appropriate preparations were made.

After some 10 minutes, there was no longer maximum dilation of the pupils and after a further 10 minutes they were again of a uniform size, small and exhibited reactions on exposure to a light stimulus, so that it was decided to dispense with further surgical intervention for the present. For a duration of some 30 minutes after onset of the symptoms of intracranial hypertension, there were episodes of tachycardia arrhythmia and significant extrasystoles that, however, did not require therapy.

A central venous catheter and a cannula for intravenous blood pressure monitoring were introduced and anaesthesia was continued with 500 mg/h thiopental, 500 mg/h propofol, 500 µg/h fentanyl and approx. 5 – 10 µg/min norepinephrine.

There were no subsequent changes to pupil status.

AirMedEvac and

surgical intervention

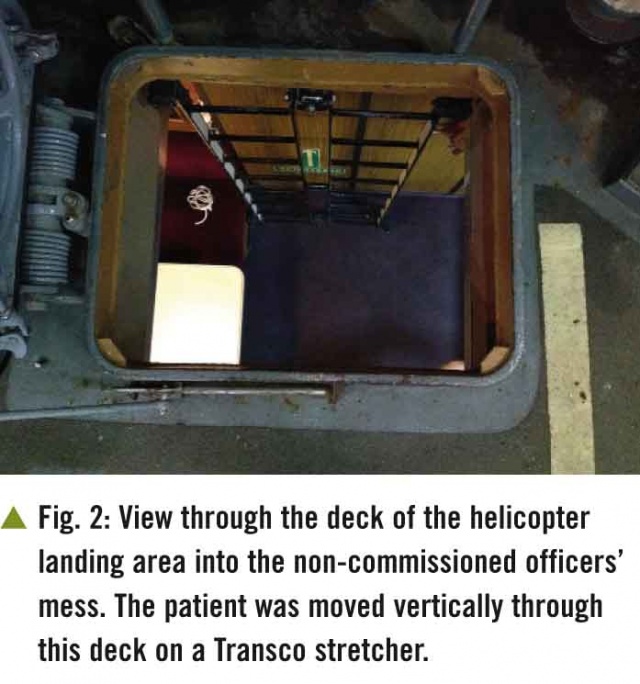

In the meantime, the Indian aircraft carrier VIRAAT had been notified of the medical emergency and had taken course towards the Bremen. By 5.00 pm, the ships were within helicopter operational radius and the patient was prepared for evacuation to Mumbai on a Sea King helicopter of the Indian Navy. A Transaco stretcher was used for the transport of the intubated and threefold anaesthetised patient, whose cardiovascular status was being maintained with the aid of catecholamines, from below deck to the helicopter landing pad. This made it possible to securely manoeuvre the patient in a vertical position through the hatchway of the non-commissioned officers’ mess.

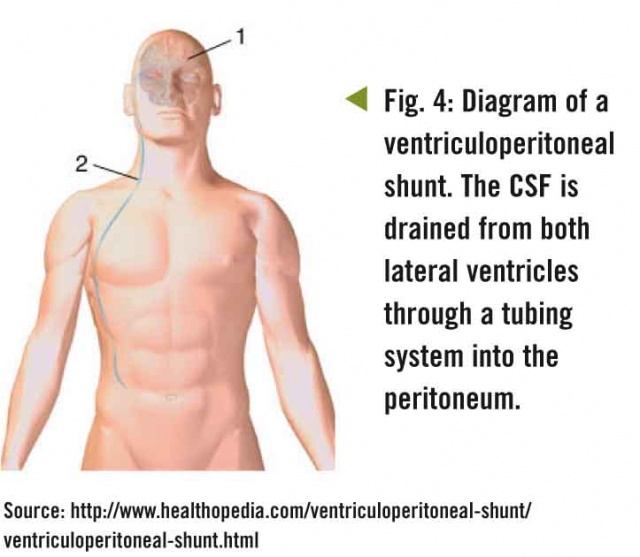

After a flight lasting some 90 minutes, we reached the Indian Navy Hospital Ship Asvini in Mumbai. The patient was released into the care of the hospital shock room team and was immediately subjected to CCT. The presence of a colloid cyst (approximate size: 2.5 x 2.5 cm) was detected in the third ventricle. This was exerting pressure on both foramina of Monro resulting in major occlusive hydrocephalus.

Immediately after diagnosis, a bilateral ventriculoperitoneal shunt was introduced under continued anaesthesia.

On the morning of 16 August 2012 at around 8.00 am, the patient was successfully extubated. After a sufficient recovery period, no major neurological problems were detected apart from significant retrograde amnesia. The suitability of the patient for transport was assessed and preparations were then made for his evacuation to Germany. On 17 August 2012, he was transported without experiencing complications on an Airbus 319 MRT of the German Luftwaffe initially to Stuttgart, from where he was transferred to Ulm Bundeswehr Hospital. On the day of his arrival, resection of the colloid cyst was performed and the VP shunt was removed.

Discussion

Incidence of and treatment options for colloid cysts

A colloid cyst is a benign cystic lesion that normally develops in the region of the third cerebral ventricle (2). Symptomatic colloid cysts are rare and occur in only 3.2 cases per 1,000,000 of the population annually (3). As colloid cysts are, in histological terms, benign tumours, the general prognosis is good. They can cause serious neuroanatomical problems when they are located at the roof of the third ventricle near the foramina of Monro. As most intracranial colloid cysts develop immediately in the vicinity of the physiological bottleneck region of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation between the lateral ventricles and the third ventricle, they can be the cause of occlusive hydrocephalus. The disorder is usually chronic, but it can become peracute and even be the cause of sudden death.

As the cyst membrane secretes a gelatin-like, viscous material, its volume gradually increases so that the cyst presses on surrounding structures and, more seriously, it can impair the circulation of the CSF. In the forensic literature, there are several reports of the sudden death of still relatively young patients as a result of acute CSF blockage due to the presence of a colloid cyst in the third ventricle (2, 4, 5).

The most common symptom associated with colloid cysts is intensive, intermittent, frontally-accentuated headache; this can also often be posture-associated in contrast with the less intense, more diffuse pain experienced by patients with other forms of cerebral tumour (6). Other symptoms are ataxia of gait, neuropsychological deficits and memory disturbance (7).

Medical emergency measures under difficult conditions

In the case in question, it had to be assumed that the symptoms of intracranial hypertension had a non-traumatic cause as no further investigation was possible. In the decompensation phase of intracranial hypertension, surgical intervention in order to reduce pressure was considered as an ultima ratio. However, without detailed information on the cause of the hypertension, there were fundamental issues that first needed to be considered. It was not possible to identify which side was affected. Assuming the presence of cerebral swelling, there was the possibility that cerebral material would expand when the dura was opened, so that a hemicraniectomy represented a possible option. But the only procedure with an acceptable level of risk would be the introduction of a provisional external ventricle drainage system in the form of a CVC or pleural drainage tube, as no specially designed ventricle drainage tubes were available in the medical supplies available. However, in hindsight it is possible to speculate that one-sided pressure reduction, in view of the centrally located cause of the blockage, might in this case have resulted in a midline shift and thus additional damage.

The conservative measures adopted in order to reduce intracranial pressure were based on the guidelines for the treatment of craniocerebral trauma (8). In this case, it can be assumed in retrospect that the forced hyperventilation and the associated reduction of intracranial volume resulted in release of the pressure on the foramina of Monro, thus breaking through the vicious circle of occlusive hydrocephalus. Over a period of some 2 hours, hyperventilation was gradually returned to normoventilation at an ETCO2 of 35 mmHg. Despite this, there was no renewed increase in intracranial pressure in the 8 hours prior to emergency surgery in the hospital ship in Mumbai. At the same time, it is possible that the 30° elevated posture given to the upper body of the patient as recommended in the guidelines during treatment onboard actually held the colloid cyst in place, thus impairing drainage, while this was not the case while the patient was prone and repeatedly moved during the 4-hour trip to Mumbai.

Although this was a case of a very rare disorder, the death of the patient during foreign deployment would have been an unacceptable result. It was only due to luck, resolute intervention and the excellent support provided by the Indian Navy that a lethal outcome was avoided.

This case underlines the importance of the presence of an ‘on-board medical specialist team’ but also demonstrates the limitations for the treatment of intensive care cases on board a frigate.

References: [email protected]

Date: 12/31/2012

Source: MCIF 4/12