Report: MCM Bricknell, E-J Grigson (UK)

International Engagement with the Indigenous Health Sector

This paper presents observations from the engagement of international military medical services with the Afghan security forces medical services.

It starts by presenting a model for understanding the health sector of a country in crisis. It then summarises the efforts to develop the medical services of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and Afghan National Police (ANP) since 2001. The paper focuses on experiences and observations at the operational and tactical level from our engagement with the Afghan security forces in 2009/10. The paper concludes with examples of practical challenges and solutions in developing capacity and capability for the medical services of the ANA and ANP in the Southern region of Afghanistan.

Introduction

Engagement of international military medical services with the indigenous health sector is essential, but there are different requirements for the military and civilian sectors. This paper builds upon previous discussions of the development of the medical support arrangements for indigenous security forces [1] and focuses on experiences and observations at the operational and tactical level from UK engagement with the Afghan security forces in 2009–10. The practical challenges and solutions in developing capacity and capability for the medical services of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and Afghan National Police (ANP) in the Southern region of Afghanistan are described.

Discussions of Security Sector Reform (SSR) within international efforts at Stabilisation Operations or Counter Insurgency (COIN) operations [1] emphasises the importance of holistically considering a State’s responsibility for ensuring the security of its population from both internal and external threats.SSR encompasses support to all aspects of the State’s security system including political control, police, the armed forces, the intelligence services, the judiciary and the penal system. Resources expended by the State’s security system need to be balanced between the resources available and the magnitude of the threats.

UK military medical services personnel have contributed to the development of the medical services for the indigenous security forces in a number of locations such as Brunei, Oman, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Iraq. The relevant issues can be considered at the contextual, strategic, operational and tactical levels and this framework is applicable when considering International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) medical engagement with the medical system supporting the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) – both ANA and ANP.

Context

An SSR strategy has been an enduring element of the international military campaign in Afghanistan.However the pace of development of the Afghan security forces was accelerated in 2009 as it became clear that greater numbers were required as part of the ‘population-centric’ COIN strategy introduced by General McCrystal. This included a significant shift of emphasis from the ANA to the ANP in recognition of the importance of police services in protecting the population after military forces had cleared insurgent forces from an area. The style of engagement with Afghan security forces also shifted.Initially the ‘train and equip’ programme was run by a military headquarters, Combined Security Transition Command – Afghanistan (CSTC-A), separate from the ISAF Headquarters. This resulted in ISAF planning and executing security operations separately from the ANA and ANP. This was changed to a ‘mentoring and partnering’ mission in which ISAF forces would live and fight alongside Afghan security forces. The new ISAF headquarters, ISAF Joint Command, became responsible for operational aspects of mentoring and partnering including force generation of mentors and partners. Regional Commands (RCs) became responsible for mentoring and partnering with tactical forces. In addition, all security operations would be planned together, eventually resulting in Afghan leadership with ISAF forces in support. Underpinning this new concept was the expectation that the Afghan security apparatus would become increasingly accountable to their population. In this model, the key relationship is that between the ISAF individual or unit and their Afghan partner or unit. The role of mentors is to provide continuous engagement in order to facilitate this partnering relationship and is complementary. This is very different from the role of the mentor in a ‘train and equip’ mission in which they work to deliver people and units capable of independent operations.

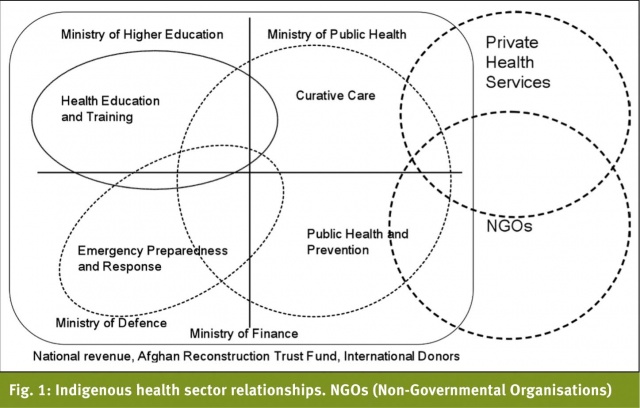

There are a multitude of inter-relationships between various stakeholders in each national health economy that are applicable to Afghanistan (Figure 1).

The Ministry of Finance is responsible for the allocation of funds from both national and donor sources to each Ministry that provides health services. In addition, three major donors – the World Bank, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Union – directly manage funds for the provision of health services. The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) is responsible for the procurement of curative care, public health, and preventive medicine services for the whole population. Whilst the MoPH is a stakeholder in Health Education and Training, this is the responsibility of the Ministry of Higher Education. This ministry runs medical facilities to be able to place students into health-service delivery environments and to maintain the clinical practice that clinical teachers require to maintain their skills. The MoPH is the lead ministry for emergency preparedness and response but both the Ministry of Interior (MoI) and the Ministry of Defence (MoD) own command and control centres and ambulances that respond to security incidents. The MoD is responsible for the provision of health services to the armed forces whereas the MoI is responsible for medical support to the Police and also for the provision of medical care to detainees/prisoners. However the MoI has very limited medical services and so has to use MoPH and MoD medical facilities. While the Ministry of Defence needs to recruit members of the health sector workforce, there are efforts to ensure profession-specific training is delivered under the oversight and licensing arrangements of the Ministry for Higher Education. The MoD is negotiating special access and funding arrangements to cover circumstances where curative medical care for military personnel and their dependants is best delivered through MoPH facilities. Finally, it is essential to consider the private or informal healthcare market where most healthcare workers earn the majority of their salary. The size of this market will be affected by the comparative value of government salary levels to the costs of living and the role of ‘graft’ in personal economic influences.

The funding for medical support for security forces is found from the Ministries of Defence and Interior, both of which receive considerable assistance from the US Department of Defence though the CSTC-A. International Agencies or Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) do not provide assistance to military medical services. Clearly the medical services compete with other security capabilities such as tanks and helicopters. The financial support provided depends on organisational and political factors but is heavily dependant on the lobbying capability of senior members of the military medical services. This emphasises the need to mentor indigenous military medical personnel in military politics and staff procedures in order that they can compete effectively in this environment.

Strategic issues

Initially the development of the ANA was the responsibility of the US through CSTC-A and separate from the ISAF mission, whilst the development of the ANP was the responsibility of Germany. In 2006 it became clear that CSTC-A should contribute to the development of the police and additional assistance was provided by the European Union. In 2009 a new organisation, NATO Training Mission – Afghanistan (NTM-A) was established to provide NATO resources towards the ‘train and equip’ mission for the ANSF. This became a parallel organisation alongside CSTC-A because the US required a separate line of accountability for the disbursement of US funds for ANSF development.

Within the medical services, CSTC-A withdrew from responsibility for supporting the execution of medical support to Afghan security forces; this was transferred to the operational chain of command. The medical element of CSTC-A became the Medical Training and Advisory Group (MTAG) with responsibility for engagement with the ANA and ANP ‘Offices of the Surgeon General’, supporting development of medical policy for the security forces and responsible for supporting national and regional security force hospitals. Regional Commands became responsible for supporting medical planning and execution for the Afghan security forces and monitoring the progress in development of their field medical system. In addition, the training system was regionalised in order to increase throughput of recruits.

The medical system for the Afghan National Army after 2001 was originally designed around the US Army system on a linear basis with deployable medical companies and Forward Surgical Teams. This was complemented by a network of infrastructure garrison medical centres and regional hospitals. As the campaign progressed, it became clear that the utility of these deployable assets was limited and that efforts should be focussed on initial first aid, field primary care, garrison primary care, regional hospitals and tactical aeromedical evacuation. The strategic plan for the development of the ANP medical services was less well developed. All parties agreed that ANP officers needed to be trained in basic first aid and that there should be individuals employed as Combat Medics at the sub-station level. There was disagreement between the ANP Surgeon General and CSTC-A about the extent to which the ANP should have an independent primary care and hospital system rather than collaborating with both the ANA and the MoPH. The shortage of medical manpower for the ANP within Regional Command (South) made this debate irrelevant with the only issue being the balance between ANA and MoPH support to the ANP.

Operational Issues

Engagement with the Afghan medical system was across all health sectors in order to plan for the medical care of all casualties of conflict including weekly meetings with the Commanding Officer of the Kandahar Regional Military Hospital, the 205 Corps Surgeon (or Senior Medical Officer) and the 404th Mainwand Police District Surgeon. Each of these Afghan Partners also had a mentor who spent time with them daily. The ISAF partners worked hard to ensure that Afghan military doctors were fully engaged with Afghan security planning by supporting the drafting of the medical support annex for operational staffwork and coaching them for the briefing role in the formal Corps Orders briefings. Key planning sessions also included the Director of Public Health for Kandahar Province and the Director of the Mir Weis Regional Hospital. The main focus was to introduce planning into the Afghan health sector.ISAF had implicitly agreed to provide helicopter forward medical evacuation for ANSF casualties where they were operating in partnership with ISAF forces and also to move civilian casualties with life, limb or eyesight threatening injuries; this also applied to hospital care. The goal was to increasingly shift the primary destination of ANSF casualties from ISAF to ANSF hospitals with acceptance of secondary referral if required. This required an acceptance that clinical outcomes may not be as good if these Afghans were received directly by ISAF hospitals but that the only way to improve the Afghan medical system and to hold its leadership to account was by ensuring that they were passed the clinical workload. Specific clinical scenarios were agreed to ensure that cases that would exceed Afghan capacity were directed to ISAF facilities where there was a realistic likelihood of a worthwhile clinical outcome.

The biggest challenge for all aspects of ANSF development at the Regional level is the gap between authorised manning and actual manning. The motivation of medical staff was vulnerable because of the impact of the additional risk of military service in the south is compounded by separation from family and the lack of opportunity for private practice. This is partially alleviated by additional pay and a (unfulfilled) promise of preferential selection for specialist training. Manning of medical units is further complicated by the lack of nurses and by difficulties in establishing qualifications and competencies for individuals assigned to physician appointments. Whilst the Afghan army has been running Combat Medic training for several years, there was also an endemic shortfall of people against Combat Medic posts for the reasons cited above and also the mis-employment of qualified individuals by military commanders because of the literacy and wider skills of medics. Within the Afghan National Police, there was almost no medical staff with all of their casualties being taken directly into the civilian medical system. From the ISAF perspective, there was also an institutional shortage of medical staff available to support mentoring and partnering because few nations were prepared to resource this requirement above the manning necessary to provide medical support for their own forces.It required extensive marketing to persuade ISAF medical units that the medical task was extended to include partnering and mentoring for ANSF units within their battlespace. Our role was to broker information in order to enable all forces with a medical mentoring mission to have access to the wide range of policies, educational material and other background information that they needed to fulfil their role.

About 60% of patients in the main ISAF hospital in RC(S) were Afghan, half of which were ANSF and half civilian and had a much longer length of stay than ISAF patients because of the disparity in clinical capability between the ISAF hospital and local Afghan facilities. Although there was a significant improvement in the capability of Kandahar Regional Military Hospital in 2009/10, the limited number of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds meant that it was often full. Therefore the movement of ANSF patients from the region became the solution to bed management in RC(S). Whilst a simple idea, this was a complex issue as every component of the patient movement system had to be developed in order to ensure continuity of clinical care from a bed in Kandahar Regional Military Hospital (KRMH) to a bed in the National Military Hospital (NMH) in Kabul. The first step was to create an expectation that the NMH would receive ICU patients from the regions and so needed to manage bed capacity across the ANA hospital system rather than just provide hospital support to Kabul and its environs. We needed to support the Afghans to develop an aeromedical evacuation capability and that this was a legitimate task for the Afghan Army Air Force. Finally there needed to be a command and control system to regulate patients between hospitals.

Tactical Issues

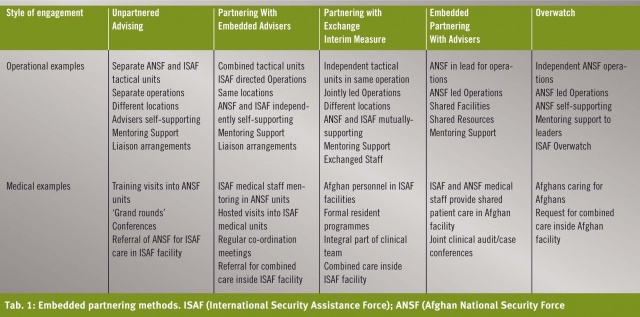

The key to effective development of the Afghan medical services is to focus on the endstate of an Afghan caring for an Afghan. Too often, Afghan interpreters are used to facilitate ISAF personnel to care for Afghans rather than changing the paradigm and to use interpreters to enable mentoring of care provided by Afghans. This clearly starts with training and equipping Afghan medical personnel, but as the personnel leave the training pipeline they require employment in a medical role with an appropriate mentor. Some of the early mentoring activity can occur within ISAF medical facilities to enable Afghan medical staff to care for those Afghan casualties in the ISAF medical system. As individual competences develop, then this medical care should be delivered within Afghan facilities with ISAF mentorship. Further development of organisational capability is facilitated by partnership where the commanders of matching ISAF and ANSF units and their command teams work together to improve the collective competencies of the Afghan units. For the long-term, the Afghans must find their own solutions themselves. It is essential to provide pre-deployment training and orientation for personnel who are going to be working with the ANSF as a result of the cultural differences between personnel from Western nations and Afghans. There a range of educational methodologies to support mentoring and partnering including formal teaching sessions, in-placement of clinical staff and joint case management (Table 1).

The development of KRMH was the most important element of Afghan medical capacity; it opened in 2007 with two operating theatres, imaging and laboratory services and 50 nursed beds which included six intensive care beds. The US provided a dedicated mentoring team to this facility including a hospital physician, a nurse, patient administration, laboratory technician, x-ray technician and a logistician.Building clinical capacity involved careful negotiation with the hospital Commanding Officer as this required not only extending individuals’ clinical skills but also the development of organisational skills and agreement that clinical responsibility extended for the duration of a patient’s admission rather than just the period of the clinician’s presence at the hospital. This included raising standards of nursing care and developing local professional relationships between medical and nursing staff. The proximity of the ISAF hospital on Kandahar Airfield enabled specialist medical staff (including nursing staff) to support the efforts of the mentoring team.

The 205 Corps Surgeon mentor invested considerable effort to encourage the ANA Corps Surgeon and his staff to engage with the ANA General Staff in the planning process up and down the chain of command. This required considerable patience as many of the approaches to medical planning that ISAF take for granted have not been part of the Afghan experience. Both the 205th Corps Surgeon and the 404th Maiwand Police District Surgeon were supported to visit their areas of responsibility and conduct a formal audit of capabilities and capacities of their medical systems. They produced joint reports that were submitted to both the Afghan and ISAF chains of command. Both ANA and ANP Surgeon Generals in Kabul were visited and the focus on combat lifesaver and sustainable primary care support to deployed forces reinforced with the development of regional Combat Medic training supported in order to increase the generation of medical capacity. The 205 Corps Surgeon was supported in his decisions on the allocation of his personnel across the Corps and assisted with the tracking of the individuals to their actual location for employment. ISAF Task Force medical directors were encouraged to identify ANSF medical units in their area of responsibility to ensure the development of partnership relationships between battalion aid stations and the equivalent Afghan units. Each were challenged to provide a photograph of an Afghan being cared for by an Afghan in an ISAF field medical unit to illustrate their commitment to partnering (Figure 2) .

Whilst considerable efforts were made to support the development of pre-hospital and primary medical care capabilities of the ANA, endemic undermanning was the main constraint on progress. Overall manning at Corps and below for medical staff was less than 70%, with medical staff even lower. Many of the individuals appointed as physicians had very little medical knowledge and certainly would not have met any Western standard. This was compounded by the recognition that the South was a dangerous place with very few incentives for service in this area.

Conclusions

Significant improvements in the competencies of the Afghan medical leadership to support tactical security operations were made and the KRMH has become the leading Afghan trauma hospital providing one of the very few intensive care units in the country. Developing indigenous medical services is a complex and challenging task but it is also one of the contributing tasks that enable international military forces to handover security responsibilities to the Afghan government.

Date: 02/19/2014

Source: MCIF 1/14