Report: N.T. TARMEY, D. EASBY, C.L. PARK, P.F. MAHONEY, S. BREE (UK)

Deployed Medical Care – UK Military Guedelines for Anaesthesia

Paediatric Anaesthesia for Overseas Operations: UK Military Guidelines

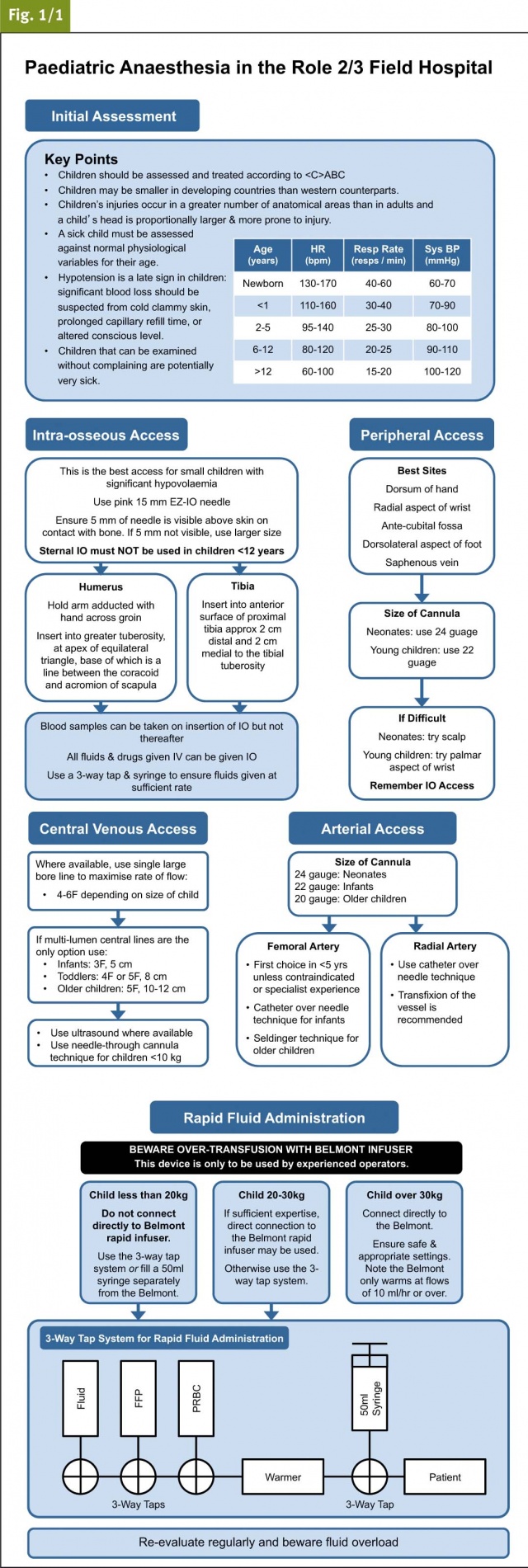

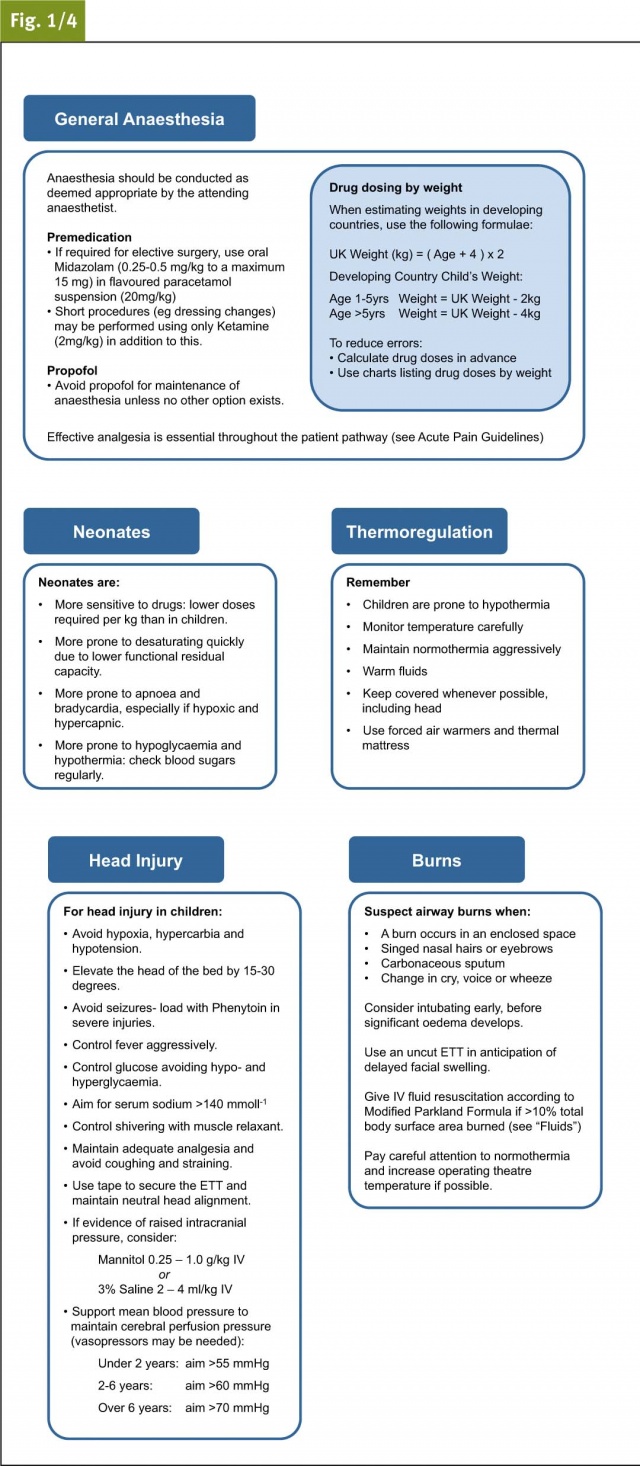

In the United Kingdom Defence Medical Services (UK-DMS), we have recently completed a major revision of our Clinical Guidelines for Operations (CGOs). Here we present our guidelines for the anaesthetic management of paediatric casualties, aimed at providing practical, concise guidance for deployed clinicians. These have been extensively updated to include current evidence and lessons learned during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last ten years.

Introduction

Although military facilities may not be designed primarily for paediatrics, the UK-DMS experience is that severely-injured children will often make up a significant proportion of a field hospital’s caseload. Our guidelines are aimed at the competent, but non-specialist anaesthetist dealing with paediatric trauma in an austere environment. As such, we suggest these may also prove useful to other international military and civilian anaesthetists managing paediatric anaesthesia in the field.

The ABC Approach

Our guidelines differ from standard civilian practice by advocating the ABC approach to care, where represents catastrophic haemorrhage as the most urgent initial priority. This reflects our approach to adult trauma, introduced in response to the high incidence of severe haemorrhage from penetrating trauma in patients of all ages. Another difference between our initial approach and civilian guidelines is our use of adjusted weight calculations for children from developing countries. Our experience is that children in the developing world typically weigh less than their western age equivalents, so an adjustment factor is included in the UK-DMS calculation shown here.

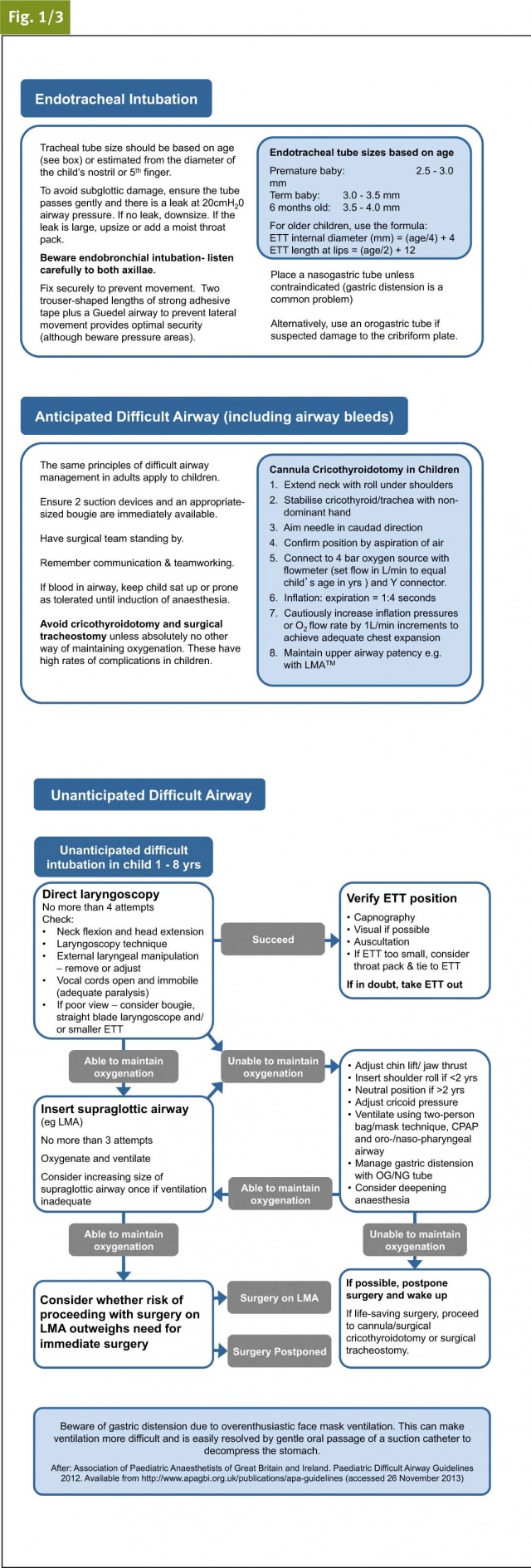

Airway management

When managing an anticipated difficult airway in paediatric trauma, most of the key principles of adult difficult airway management still apply. One of the most important goals in this challenging situation is maintaining excellence in human factors- including effective team-working, maintenance of situational awareness, and clear communication.

One key difference between paediatric and adult difficult airway management is that surgical cricothyroidotomy and surgical tracheostomy should be avoided in children unless there is absolutely no other way of maintaining oxygenation. These procedures are associated with high levels of complications in children and alternative approaches (eg temporary needle cricothyroidotomy) may be safer and more effective.

Guidelines produced by the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (APA)1 are widely accepted in UK civilian practice. Our UK-DMS guidelines have been developed according to the same principles, whilst accounting for the limited range of paediatric airway equipment available in the deployed field hospital

Fluid Resuscitation

UK National Patient Safety Agency guidelines recommend that, for children not requiring massive transfusion, isotonic fluids or 0.45% sodium chloride should be used instead of 0.18% sodium chloride for post-operative maintenance fluids. Additional dextrose is suggested but there is little evidence for the dose or concentration to be given. In contrast, current APA guidelines suggest that Hartmann’s solution (lactated Ringer’s) with added dextrose would be ideal, although this is not commercially available. There is no agreed UK national standard, and there is a limited choice of fluids on operations.

We have decided that the safest way to avoid hypo- and hypernatraemia is to use Hartmann’s solution with regular blood sugar monitoring. When additional dextrose is required to prevent hypoglycaemia, this can be added to the Hartmann’s solution at the point of care.

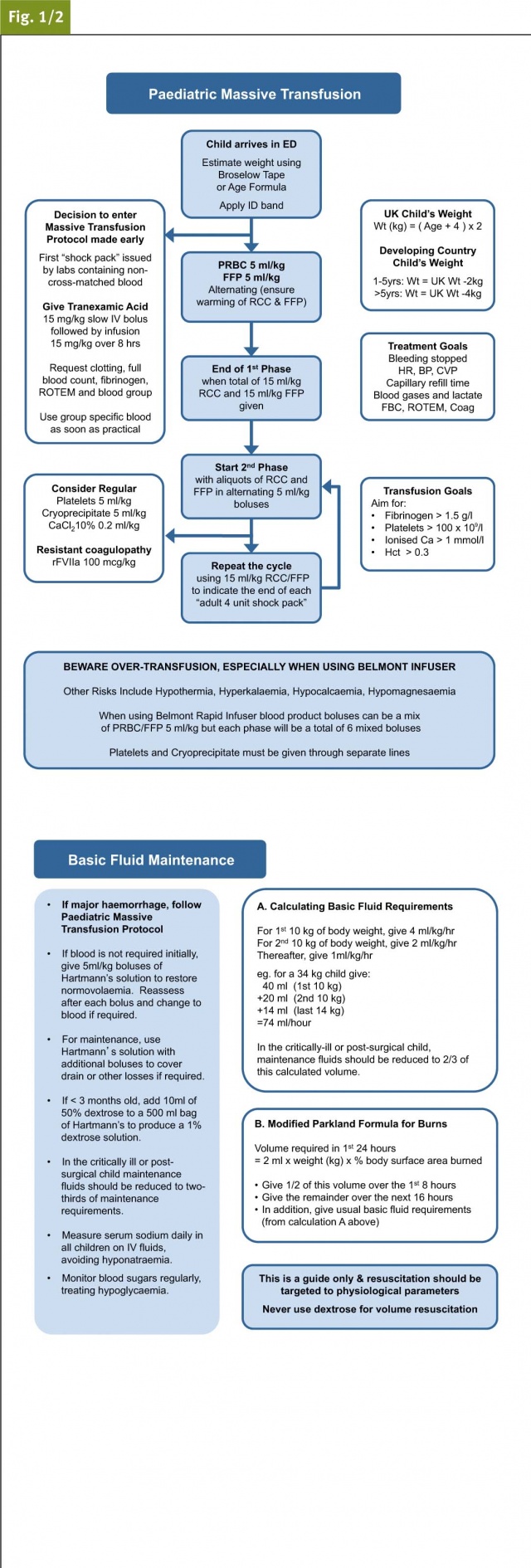

Massive Transfusion Protocol

For children with severe bleeding, our paediatric massive transfusion protocol is also included in these flowcharts. In summary we recommend that red cell concentrate (RCC) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) are alternated in 5 ml/kg boluses until the required end points of resuscitation are achieved. In addition regular boluses of 5 ml/kg platelets, 5 ml/kg cryoprecipitate and 0.2 ml/kg of 10% calcium chloride should be considered after the first 15 ml/kg RCC and 15 ml/kg FFP.

In the UK-DMS, we use the Belmont Rapid Infuser device (Belmont Instrument Corporation, Billerica, USA) to deliver blood and blood products during massive transfusion in the deployed field hospital. We have found this device to be safe and highly effective. There are important safety considerations when treating children. Our devices are programmed to deliver a minimum fluid bolus of 100 ml, making them unsuitable for patients under 20 kg.

We recommend using an alternative method of delivery (eg 50 ml syringe and in-line warmer) for patients under 20 kg, and extreme caution must be applied when using the Belmont device for patients between 20 and 30 kg.

Conclusion

These guidelines provide straightforward guidance for the non-specialist anaesthetist managing major paediatric trauma in the deployed environment. While many of the concepts are similar to accepted guidelines for adult and urban civilian trauma, they include a number of important adaptations. These have been developed based on current evidence and extensive experience from recent conflicts. We hope that these may also prove valuable to other military and civilian anaesthetists managing paediatric anaesthesia in the field worldwide.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Miss Alison Bess, Editor for Clinical Guidelines for Operations and Administrator for ADMACC and ADMEM, for her valuable contribution to the drafting and editing of these guidelines. We also wish to acknowledge Maj D Inwald RAMC (V) for his expert advice on paediatric anaesthesia and resuscitation.

References: [email protected]

Date: 03/20/2014

Source: MCIF 1-14