Article: MCM BRICKNELL (UK)

Medical Lessons from OPERATION MOSHTARAK Phase 2

This paper is a narrative description of the planning and execution of the medical support plan for OP MOSHTARAK, the Combined Team security operation in the towns of Nad Ali and Marjah of Central Helmand in February and March 2010. The aim is to describe the key events that influenced the development of the medical plan and how these unfolded during the operation in order to identify observations and lessons learned to improve processes for managing medical support to future operations. The paper illustrates how the principles for planning and managing medical operations are applied in practice.

Introduction

By the middle of 2009, the threat posed by insurgent forces in the area of the towns of Marjah and Nad Ali in Helmand province, Southern Afghanistan, was de-stabilising attempts at expanding the influence of the government of Afghanistan out from the provincial capital of Lashkar Gah. The military operational concept was designed to secure Central Helmand under the title Operation MOSHTARAK, following the ‘Shape, Clear, Hold, Build’ (SCHB) framework within the new doctrine for counter-insurgency operations. It was designed from the ‘Build’ backwards, dependant on building strategic and political consent from all stakeholders, most especially the Afghans. The central component was based upon a district development plan both designed and resourced by the Afghans, which would be supported by security operations. The security operation was planned as an Afghan/ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) partnership based upon the premise that security during the hold and build phase would be led by the Afghan National Police (ANP).The operation would not start until there was a plan to deliver sufficient security forces (ISAF, ANP and Afghan National Army (ANA)) in a phased manner across the SCHB construct. This depended upon US and UK strategic allocation of resources, Afghan Ministry of Defence (MoD) and Ministry of Interior (MoI) re-assignment of security forces across Afghanistan and commitment to the plan from all tiers of Afghan government including across government ministries.

The military operational plan was the responsibility of Headquarters (HQ) Regional Command (South)(RC(S)) at Kandahar airfield, formed from Headquarters 6th (UK) Division with additional personnel from the US, Australia, the Netherlands, Canada, France and Singapore. The staff for this HQ were termed Combined Joint Task Force 6 (CJTF 6) and took over from CJTF 5 in November 2009.The main logistics hub for all NATO operations in Southern Afghanistan was located at the airfield in Kandahar, the capital of Kandahar Province, whilst the Helmand provincial logistic hub was at Camp Bastion, all under the responsibility of (RC(S)).

There were three military forces from the UK Army and US Marine Corps and Army. The tactical plan saw an escalation of interdiction operations during the ‘Shape’ phase followed by the insertion of a large combined force (ISAF and ANA) to a number of helicopter landing sites (HLS) on the night of 12/13 Feb 2010.These forces would then extend their tactical influence and achieve link-up with ground forces over the next few days. Opposition freedom of manoeuvre would be disrupted by the seizure of a large irrigation canal, essentially isolating the two separate Task Force areas and preventing any movement by opposition forces between the two other taskforce areas of operation.

This paper is a narrative description of the planning and execution of the medical support plan for Op MOSHTARAK. The aim is to describe the key events that influenced the development of the medical plan and how these unfolded during the operation in order to identify observations and lessons learned to improve processes for managing medical support to future operations. It provides a practical example of the application of the principles of planning and management of medical support to operations.

Medical Planning

Medical planning started at the same time as the CJTF 6 military planning staff began to review the estimate conducted by the previous HQ for this operation. This confirmed that the surge of forces to RC(S) to conduct a deliberate theatre-level operation was likely to require an increase in medical support.

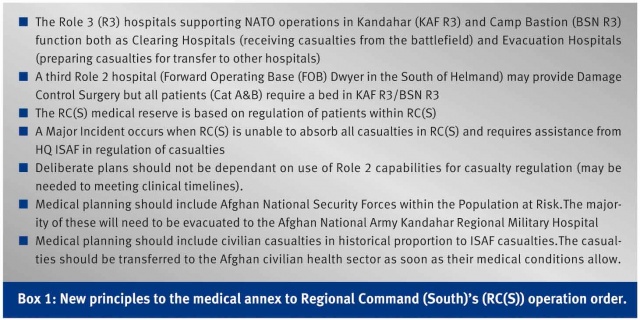

The Medical Annex to the new RC(S) operation order established a number of new principles (Box 1). These principles explained the RC(S) approach to medical planning and reinforced the point that medical planning should shift from capability to capacity planning. The Role 3 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) was considered to be the critical capacity in the medical system.

The next challenge was to shape the context for medical support and to ensure both NATO and national chains of command understood the requirement to augment ISAF to support this operation. The key event was the US Central Command Surgeon’s conference in the second week of November 2009. This provided the opportunity to share the RC(S) view of medical support to Central Helmand operations with all higher headquarters. There was agreement that RC(S) would require medical augmentation, but not how this might happen. These discussions provided the basis upon which to build the next phase of negotiation – how much was needed and who might provide it.

Casualty Estimation

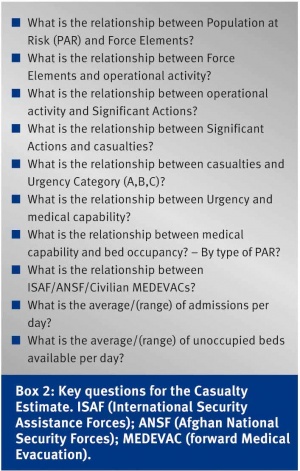

It was clear that any argument for medical augmentation was going to hinge upon the Casualty Estimate. The only reliable source of comparable data was from the UK surge operation, Operation PANJAY PALANG, conducted in July 2009, and therefore this was considered to be the source of baseline ratios for casualty estimation. Whilst the previous casualty estimate had come to the conclusion that more resources were required, there was no institutional memory that could explain the methodology behind the analysis. The new CJTF6 staff de-constructed the previous analysis and then re-built the casualty estimate methodology (Box 2). This analysis was a collective effort between RC(S), US Task Force Medical (South), Kandahar Airfield (KAF) Role 3 Hospital, UK Joint Force Support (Afghanistan) medical staff and the UK Role 3 hospital staff at Camp Bastion. This served both to ensure coherence of the logic and also to ensure collective ownership of the product. The results were presented in a variety of formats and against a range of operational scenarios.

Whilst the precise tactical employment of forces was still being developed by RC(S) planning staff, the revised analysis confirmed the need to augment RC(S) medical resources for the operation. A formal staff paper was constructed that linked the Casualty Estimate to the additional Role 3 capacity required. It also established the need for additional Medical Evacuation (MEDEVAC) and Tactical Evacuation (TACEVAC) capacity, including fixed wing (FW) airframes, and confirmed the centrality of the Kandahar Regional Military Hospital (KRMH) in caring for Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and high dependency civilian casualties. It made provision for the handover of minor ANA casualties to the ANA Garrison Clinic at Shorabak near Camp Bastion. This paper provided the first formal request for additional personnel and equipment to the UK Role 3 at Camp Bastion and started the debate between in-theatre and out-of-theatre solutions.

RC(S) conducted a review of aviation support, including medical evacuation that showed that the volume of patient movement between medical facilities was having a disruptive effect on MEDEVAC coverage and that TACEVAC should be considered as a separate helicopter (Rotary Wing, RW) aeromedical evacuation taskline. Further discussions led to the development of the concept of TACEVAC ‘pull’, or patient retrieval, to complement the more urgent TACEVAC push from Role 2 units. An operational concept was developed that enabled the use of the UK Critical Care Air Support Team (CCAST) personnel on a general support helicopter or a US ICU team on a similar helicopter who could deploy from each of the Role 3 hospitals to collect a high dependency patient and bring them back to R3 under high level medical supervision.

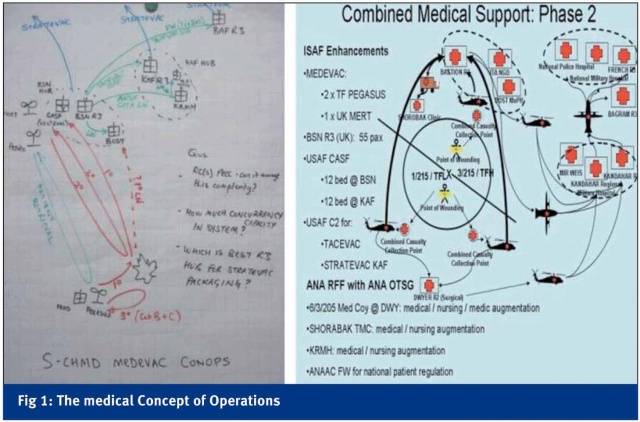

The Patient Evacuation Co-ordination Cell (PECC) is the mission essential component of the HQ RC(S) Medical Branch. After a full review of the structure for control and co-ordination of MEDEVAC in RC(S), the PECC was re-structured and augmented to enable 24 hour working of the Medical Operations and Evacuation Co-ordination desks with an additional desk officer for the peak period of 0600 - 2000. The PECC in the Combined Joint Operations Centre (CJOC) was expanded by one desk. At the same time there was full review of the RC(S) medical Standing Operating Procedures (external instructions) and the internal Standing Operating Instructions in order for all stakeholders to understand the external and internal workings of the medical system in RC(S). The next stage was to develop a holistic concept of medical support that encompassed all potential victims of conflict (ISAF, ANSF, Afghan civilians). This needed to be designed with our Afghan partners and mirrored the wider approach taken by Commander RC(S) to ensure Afghan ownership of the plan. Casualties would move from point of wounding to a secure helicopter landing site (HLS) under taskforce control to enable MEDEVAC using US Army, UK air force or US Air Force (USAF) helicopters balancing operational and clinical requirements under direction from the RC(S) CJOC. The primary receiving hospital would be UK R3 BSN with the Role 2 at Forward Operating Base (FOB) DWYER as a secondary receiving hospital for Category B and C patients. After initial treatment, ANSF patients would be transferred to the ANA clinic at Camp Shorabak or the KRMH. Afghan civilian patients would be transferred to the Italian Non-Government Organisation hospital, Afghan civilian hospital in Lashkar Gah or the Afghan civilian regional hospital in Kandahar, according to clinical need. A USAF Contingency Aeromedical Staging Facility (CASF) was planned to deploy to increase aeromedical evacuation preparation capacity at both the UK R3 BSN and the KAF R3 to enable re-distribution of ISAF, ANSF and civilian casualties within RC(S), enable direct strategic evacuation of ISAF casualties from KAF R3 and theatre-wide re-distribution of ANSF and Afghan civilians to Kabul. The ‘white board’ version and the final published version of the medical concept of operations (CONOPS) are shown in Figure 1.

Two ‘tabletop’ briefings in the UK R3 BSN and KRMH introduced the concept of operations for the RC(S) medical support plan and allowed discussion by all relevant RC(S) stakeholders. It also served as a development opportunity for our Afghan partners.

The Corps Surgeon of the ANA 205 Corps and the Commander of the KRMH shared the responsibility of presenting the RC(S) medical support plan with the author at the Combined Team briefings to subordinate commanders and also to senior ISAF and Afghan representatives. This cemented the relationship between RC(S) and Afghan senior medical staff and provided a foundation upon which the mentors and RC(S) Medical Branch staff supported the ANA medical staff to develop their own plan.

The RC(S) Medical Plan for Op MOSHTARAK was published as a standalone order on 12th January 2010.This confirmed the provisional agreements made by all of the external contributing organisations and also directed the mechanism for the final refinement of attribution of personnel by contributing nations against the medical augmentation requirement.

The medical plan now moved from the J5 planning stage to the J35 refinement stage. A RC(S) Medical Execution Checklist was created and posted to the RC(S) medical branch intranet page. This enabled the RC(S) medical community to track progress on all of the outstanding issues affecting the Op MOSHTARAK medical support plan.

Two formal Rehearsal of Concept (ROC) drills, one for MEDEVAC and one for TACEVAC, were attended by over 30 people and provided an effective opportunity for frank discussion surrounding the complexity of managing both types of medical evacuation across a number of different taskforces and destination facilities. These discussions highlighted issues over reports and returns, contingency plans, management of detainees and medical rules of eligibility that were resolved and communicated as amendments to the plan through the RC(S) Daily Consolidated Order. The need for a mass casualty plan was considered and deemed unnecessary. There were to be three escalations of response to an increase in medical demand; the first by casualty regulation within the region, the second by requesting out-of-region TACEVAC and the third requesting additional medical personnel to increase capacity in the region.

The daily sequence of medical activity was driven by the medical rounds in each of the two R3 hospitals. These were conducted 12-hourly and informed a hospital evacuation co-ordination meeting in each hospital. The evacuation plan was then confirmed by UK and US national FW aeromedical evacuation planners and any gaps were passed to HQ RC(S). Monitoring of the plan was based on a six-hourly bed state report listing the evacuation plan for each hospital patient. A daily RC(S) medical conference call, run through Adobe Connect software and hosted on the NATO communication system, ensured medical command oversight of the tactical activity, medical workload and evacuation plans.

The final refinement of the tactical plan included a review of medical risk and capacity requirements. It was assessed that the greatest risk during the aviation insertion was a mid-air collision, although less than a normal training exercise because of the current experience of the pilots and the level of medical cover was much greater than would be provided for training. There was a risk of insurgents hitting a helicopter with ground-to-air weapons, although again, the preparatory assessment of helicopter landing sites was greater than usually conducted for aviation operations elsewhere in the ISAF mission. The command and control arrangements for MEDEVAC were adjusted for this phase so that each Air Mission Commander had launch authority from the RC(S) for one MEDEVAC taskline in order to reduce notification times and quicken response. Consideration was given to the difference between the Casualty Estimate as a forecast of activity compared to the need for the medical staff to rehearse the response to a

‘worst-case’ scenario. The assessment was that the medical support plan met the scenario of a two brigade divisional air assault operation against a battalion in a defensive position protected by a protected minefield surrounded by an in-place civilian population and was appropriately designed.

By default, ISAF provides MEDEVAC and hospital care, if there is no suitable Afghan hospital, to Afghan civilians with life, limb or eyesight (LLE) threatening medical emergencies, defined on the medical rules of eligibility (MRE) matrix as MRE Green. A MRE Amber grade of eligibility was introduced to restrict care of Afghans only to those with LLE emergencies resulting from conflict, for use if the NATO hospital bed capacity was under pressure.

RC(S) hosted a series of assurance visits and briefings on the Op MOSHTARAK medical plan including the ISAF Medical Director and the ANA Surgeon General in Kabul in late January 2010, followed by a visit to the Helmand medical facilities by the ISAF Medical Director and Deputy Medical Director, and a visit to the Kandahar combined team medical facilities by the RC(S) Director of Support.

The health planning cell in the Helmand Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) held a series of meetings with the Helmand Director of Public Health (DoPH) and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) representatives to de-conflict civilian and military healthcare activities in support of the civilian population. It was clear that the DoPH did not want any direct support from ISAF, though was grateful for assistance with MEDEVAC for the most seriously injured. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) planned to keep its own clinics open during the operation and the implementing NGO for the Basic Package of Health Services would re-open clinics in Nad Ali and Marjah as soon as the security situation allowed. The DoPH did not want Medical Civilian Action Programmes or other non-urgent, direct patient care activities undertaken by ISAF medical staff. This resulted in a framework for ISAF medical engagement in support of the civilian sector during each stage of Shape, Clear, Hold and Build.

Executing the Plan

The Commander RC(S)’s decision brief took place on 10th February 2010 and the medical plan was confirmed at full operating capability (FOC).The aviation insertion took place on the night of 12th February 2010 and achieved the aim of dislocating the coherence of the opposition response. Over the next few days, ground forces gradually expanded the area under Combined Team control and established link-up with follow-on forces moved by ground. Progress was deliberate and measured due to the density of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and pockets of determined resistance sited in well constructed defensive positions. The transition from Clear to Hold occurred during the first week of March 2010. Major presentational events were set up in order to influence Afghan hearts and minds. The overall ISAF commander and the Helmand Provincial Governor visited on 25th February and the Afghan President on 7th March.

Medical Events

Overall, the medical plan worked well with no medical facility overwhelmed by casualties and the UK Role 3 BSN functioning as a clearing and evacuation hospital. The CASF uplift to R3 BSN was hugely important in facilitating access to USAF aeromedical evacuation capacity. The UK and US Air Forces worked well to share the TACEVAC workload from Camp Bastion to Kandahar Airfield substantially decreasing the demand for helicopters to undertake this task. Both nations conducted strategic evacuation; the CASF facilitating the move of US detainees from UK R3 BSN thus keeping US detainees within the US national chain but still enabling clearance of ISAF hospital beds in Helmand. The CASF also accepted minor patients for holding prior to return to unit. The previous co-ordination with the Helmand PRT eased access to the civilian health sector enabling direct MEDEVAC of Afghan civilians to the Italian Emergency Hospital in Lashkar Gah during daylight hours. Afghan civilians, previously treated by ISAF, were transferred into the Ministry of Public Health Hospital, in Lashkar Gah. There were two interesting medical ‘quirks’. One was the potential clash with the alleviated by discussion with World Health Organisation and Afghan MoPH representatives in Kandahar and Kabul. The second was the management of two ICRC requests for safe passage for ‘war wounded’ from Marjah to hospitals in Lashkar Gah that was facilitated through co-ordination between CJ35 staff and the two ISAF taskforces.

The operation highlighted the surface-to-air threat from small arms and rocket propelled grenades to MEDEVAC aircraft. It was known that this would be a risk but there were a significant number of hits, emphasising the need for collaboration between the medical staff and operations staff in the CJOC to balance the risk to MEDEVAC aircraft with the clinical urgency of the patient.

Medical Activity

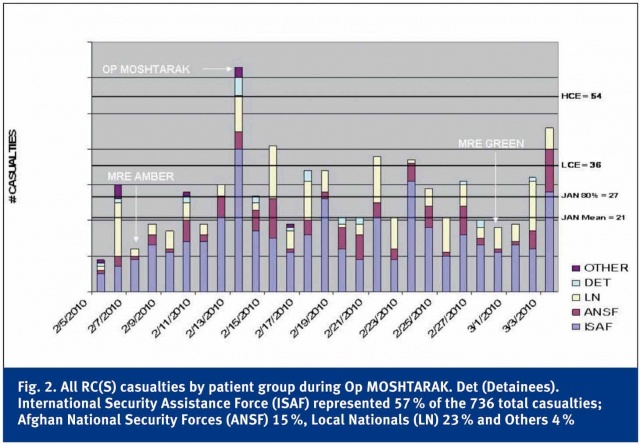

Recognising the limitation of the data supporting the casualty estimation process during the planning of this operation, a positive effort was made to prospectively capture medical activity data (Figure 2).

Seven hundred and thirty six casualties were medically evacuated from the Op MOSHTARAK area of operations with the proportions by patient population matching previous data. The higher casualty estimate was exceeded on Day 1 and the lower casualty estimate on four of the 19 days after D Day. The casualty estimate was based on the ‘Clear’ phase lasting five days- it actually went on for much longer.

The proportion of Category A, B and C of live casualties (43 %, 29 % and 27 %) of all population groups was very similar to the predicted (44 %, 32 % and 24 %). Op MOSHTARAK was not the only source of casualties during the period of the Clear phase of the operation and the majority of casualties MEDEVAC’ed in RC(S) came from outside the Op MOSHTARAK area of operations.

The US Air Force personnel recovery helicopters delivered the majority of MEDEVAC casualties to UK R3 BSN with the US Army ‘Dust-off’ MEDEVAC aircraft doing the second largest number. Whilst the majority of injuries are caused by IEDs during normal framework operations, gunshot wounds predominated for the first two days of Op MOSHTARAK.

Conclusions

The planning of the medical support for Operation MOSHTARAK followed the doctrinal medical planning process. The key issue was the requirement for augmentation of medical treatment and evacuation capacity in Helmand.

There were no unique lessons learned; just confirmation of well-established principles applied to the specific circumstances of the operation. The casualty estimate was an essential precondition to proving the case for additional medical resources. The requirement then needed to be ‘socialised’ and supported with formal operational staffwork. It was essential to engage with the Afghan Army medical services and civilian health sectors to integrate then into the plan to care for the whole population at risk. The MEDEVAC and TACEVAC rehearsal of concept drills were a vital contribution to mutual understanding across all medical stakeholders and to refine aspects of the plan. The medical augmentation plan delivered the additional capacity required. The specific practical co-ordination measures of an execution checklist and a daily conference call ensured that all key members of the RC(S) medical team shared situational awareness; this also identified specific areas that required additional concepts of operations. Finally, by prospectively capturing data, this operation allowed further refinement to the underlying evidence for casualty estimation ratios. n

Note: This article was first published in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps and is reprinted with the kind permission of the editor of JRAMC.

Authors

Brigadier Martin CM BRICKNELL L/RAMC

Head Medical Operations and

Capability Joint Forces Command

Address for the authors:

Brigadier Martin CM BRICKNELL

Northwood Headquarters

Northwood, Middlesex, HA6 3HP.

E-mail: [email protected]

Date: 07/02/2014

Source: MCIF 3-14