Article: D: Liebchen (GERMANY)

Management of urethral injuries in foreign assignments

Urogenital trauma occurs with a rate of approximately up to 12.7 % in a significant proportion of battle casualties. Up to 17 % of urogenitally injured patients suffer from urethral trauma. The proportion of penetrating injuries is higher in comparison to the primarily blunt trauma in civilian patients. Urethral injuries can lead to significant morbidity when diagnosed late or left untreated. Diagnostics and therapy follow the Guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU) and the principles of Damage Control Surgery (DCS).

Introduction

In the battles of the 20th century, a historical rate of urogenital injuries of approx. 3 % (0,4 - 4,2 %) has been observed. Analysis of the Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom operations between 2001 and 2008 revealed an increase in urogenital injuries to 5% [1]. Recent data from the US Joint Theater Trauma Registry showed that these injuries were increasing in number (12.7% in 2010) and in severity [2]. The urethra is affected in up to 17% of urogenital injuries [3]. During the Afghan conflict, the most frequent causes of injuries were from Improvised Explosive Devices (IED), mines and high-velocity bullets. Injuries caused by explosions predominate here [4].

With regard to the mechanism of injury, a distinction can be made between blunt and penetrating traumas. Whereas among civilian patients blunt urethral trauma predominates with a percentage of approx. 90%, the percentage of penetrating trauma is higher in battle casualties.

Urethral injuries are rarely life-threatening. However, they can cause profound morbidity with a permanently reduced quality of life due to subsequent urethral strictures, incontinence and impotence.

Trauma to the female urethra is rare. Often there are concomitant injuries to the bladder, vagina and rectum. The surgical treatment required is performed conjointly. Transvesicular access is recommended for the proximal urethra and transvaginal access for the distal urethra.

Diagnosis

Th

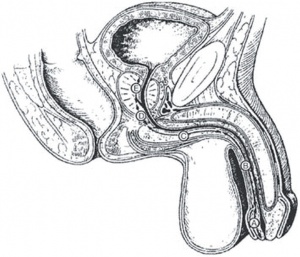

Fig. 1: Anatomy of the male urethra: (A) Fossa navicularis, (B) penile urethra, (C) bulbar urethra, (D) membranous urethra, (E) prostatic urethra.

Fig. 1: Anatomy of the male urethra: (A) Fossa navicularis, (B) penile urethra, (C) bulbar urethra, (D) membranous urethra, (E) prostatic urethra.

e male urethra comprises the penile, bulbar, membranous and prostatic urethra. The urogenital diaphragm divides the urethra into the anterior (penile, bulbar) and the posterior (membranous, prostatic) urethra (Fig. 1).

Acute urethral trauma is suspected based on the trauma event or the clinical picture of the injury. Abnormal clinical findings that indicate further diagnostic investigations are, for example, blood-stained discharge from the meatus, a raised prostate gland during the digital rectal examination as well as haematomas on the penis, scrotum and perineum. Blood-stained discharge from the meatus occurs in 37 - 93 % of posterior urethral injuries and in more than 75 % of injuries to the anterior urethra [5]. The degree of haematuria does not correlate with the severity of injury.

The retrograde urethrogram (RUG) is the examination method of choice for diagnosing and evaluating urethral trauma. This shows the affected portion of the urethra and the extent of the injury. Urethral trauma can be classified based on the x-ray image (Table 1).

| Degree | Description | Recommended management |

| 1 | Elongation of the urethra without extravasation on the RUG | No therapy |

| 2 | Contusion, blood-stained discharge from the meatus, no extravasation on the RUG | Conservative, suprapubic catheter or indwelling catheter |

| 3 | Partial interruption of the urethra with extravasation into the injured area, the urethra and/or bladder are seen proximal to this | |

| 4 | Complete interruption of the urethra with extravasation into the injured area, the urethra and/or bladder are not seen proximal to this | SPC and delayed treatment or endoscopic realignment ± delayed treatment |

| 5 | Complete or partial interruption of the posterior urethra with tear to the neck of the bladder, rectum or vagina, extravasation into the area of the injury. | Primary open surgery required |

Table1: EAU classification of blunt urethral injuries

The injured area is visualised by the extravasation of contrast medium. With grade 1 and grade 2 injuries, the urethral mucosa is intact and a transurethral catheter can be introduced. With trauma to the posterior urethra with no visualisation of the bladder on the urethrogram, a cystogram must be performed via a suprapubic cystostomy to rule out any injury to the bladder neck.

Therapy

Detailed guidelines from the European Association of Urology (EAU) on the treatment of urethral trauma were last updated in 2010 [5].

Anterior urethral trauma

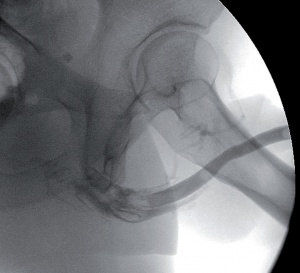

Fig. 2: RUG following a sub-total tear of the bulbar urethra secondary to blunt perineal trauma (grade 4 trauma).

Fig. 2: RUG following a sub-total tear of the bulbar urethra secondary to blunt perineal trauma (grade 4 trauma).

A suprapubic bladder catheter (SPC) or a transurethral catheter (DC) can be inserted in the event of blunt partial trauma to the anterior urethra. By using a suprapubic urine drain, further urethral trauma caused by catheter manipulation can be avoided. If there is complete break in urethral continuity (Fig. 2), in addition to inserting a suprapubic drain, an attempt can be made to perform primary endoscopic realignment. After an interval of 4 weeks, healing is reviewed via a micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG). The urine drain can be removed if the urethra is intact. A subsequent urethral stricture develops in approx. 50% of cases [6]. Endoscopic and open reconstructive procedures can be used depending on the findings.

Penetrating complete or partial traumas to the anterior urethra require extensive surgical exploratory investigations. In addition to debridement and the removal of foreign bodies, primary suturing is considered in partial defects and end-to-end anastomosis in complete ruptures. Primary anastomosis is not recommended in extensive injuries with defects of over 1.5 cm. In this incidence the ends of the urethras are marsupialised, i.e. drained off to the skin in the form of a urethrotomy and a suprapubic urine drain is inserted. Grafting procedures do not play a part in acute treatment. Plastic reconstructive surgery is performed for large defects following an interval of at least 3 months.

Posterior urethral trauma

A distinction is made between partial and complete disruption of the continuity of the urethra in the case of injuries to the posterior urethra. A complete disruption of continuity can occur in severe pelvic fractures. Erectile dysfunction occurs in 20 - 60% of patients with complete rupture of the posterior urethra. The probability is determined by the severity of the initial trauma [5].

Partial traumas to the posterior urethra are initially treated by performing a suprapubic cystostomy. After an interval of 3 weeks, healing is reviewed on an X-ray. If a stricture develops, endoscopic and plastic reconstructive procedures can be carried out depending on the findings.

In the case of complete trauma to the posterior urethra, a suprapubic cystostomy is initially performed to drain the urine. To restore urethral continuity, the therapy options are primary realignment and urethroplasty. If immediate surgical exploration is not indicated, primary realignment can be carried out following stabilisation of patients with often multiple injuries. During the preferred endoscopic procedures, it is important to preserve the bladder neck since this is often the only remaining functional sphincter mechanism. Primary open realignment is only indicated if an abdominal or pelvic surgical procedure is required as a result of other injuries, as well as in the case of trauma to the bladder neck or rectum. The decision for realignment is influenced by concomitant injuries. These can make lengthy anaesthesia or lithotomy positioning impossible. Endoscopic realignment is generally carried out within 7 days of the patient being stabilised and should take precedence given the lower morbidity. This procedure can be performed retrogradely and antegradely/retrogradely via the cystostomy channel. The advantage of the realignment procedure compared to suprapubic urine drainage alone is the lower rate of stricture (64% vs 100%). However, in two-thirds of cases, a second procedure is necessary. Both endoscopic therapy and plastic reconstruction are technically more simple following successful realignment.

Immediate primary urethroplasty to treat posterior urethral trauma is not recommended. The functional results (21 % incontinence, 56 % impotence, 49 % stricture) are not conclusive due to the view being markedly restricted by the extensive tissue trauma [8].

Delayed primary urethroplasty within 2 weeks of haemodynamic and metabolic stabilisation of the injured person is predominantly used in the case of female urethral rupture.

Plastic reconstruction

The gold standard of plastic urethral reconstruction is delayed urethroplasty after 3 - 6 months. The often severe concomitant injuries have healed after this period. The functional results in relation to restricture rate, impotence and continence are better compared to immediate reconstruction. This procedure is generally performed as a one-off intervention via perineal access. After resection, end-to-end anastomosis is used for short segment strictures. To treat longer strictures, free grafts (e.g. buccal mucosal grafts) are used for urethral augmentation.

Conclusions

Urethral trauma can occur in both injuries to the external genitalia and to pelvic region. The concept of Damage Control Surgery has been used successfully for many years in the treatment of battle casualties with multiple injuries. This describes a surgical approach, the objective of which is to stabilise severely injured patients sometimes at risk of bleeding by minimising the need for an additional surgical trauma.

Therefore the initial objective in the case of urethral trauma is to establish reliable urine drainage. If a retrograde urethrogram cannot be performed in this context, suprapubic urine drainage is the most reliable and effective procedure. X-ray diagnostics by means of a retrograde urethrogram and, if necessary, a cystogram can be conducted during the stabilisation phase. As part of the scheduled repeated surgeries carried out on haemodynamically and metabolically stable patients, the required initial urological treatment takes place depending on the findings and on the basis of the previously described criteria. If definitive plastic surgery is required, this takes place in the patient's country of origin after an interval of 3 - 6 months. Complex urethral trauma, especially to the posterior urethra with possible involvement of the bladder neck, is a major challenge for urologists when treating these kinds of battle injuries. In addition to sound endoscopic skills, pelvic surgery and plastic reconstructive procedures to the urethra must therefore form part of the fixed training content.

Image source:

Fig. 1: Jordan GH, Schellhammer PF: Urethral surgery and stricture disease. In Surgical Management of Urologic Diseases: An Anatomic Approach. St. Louis: Mosby 1992; 815-832.

Fig. 2: Hamburg Military Hospital – Radiology archives, individual patients

Address of the author:

Lieutenant Colonel MC, Dr. Dirk Liebchen

Urology Department

Military Hospital Hamburg

Lesserstraße 180

22049 Hamburg

E-mail: [email protected]

Date: 07/16/2015

Source: MCIF 3/15