Article: P. ZIMMERMANN, CH. FISCHER, S. LORENZ, CH. ALLIGER-HORN (GERMANY)

Changes of Personal Values in Deployed German Armed Forces Soldiers with Psychiatric Disorders

Deployed German Armed Forces soldiers are exposed to various traumatic events but also to situations which affect their value orientations or give rise to moral injuries. Ten focus groups were performed with n = 78 German Armed Forces soldiers after deployment to Afghanistan who were treated in the Armed Forces Hospital in Berlin due to psychiatric disorders. Numerous reasons and types of moral and values changes and also psychologic sequelae were reported, which pointed to rather individual and less stereotype reactions. The topic at hand merits greater attention for future preventive and therapeutic approaches in the Armed Forces.

Introduction

In 1992, the German Armed Forces, or Bundeswehr, deployed to Cambodia and opened a field hospital there to render medical services to both the international force under the UN-mandate and to local civilians. It was the first time, since the end of World War II, that German soldiers were deployed in significant force on a military mission outside German territory. This mission, as well as the following deployments to Somalia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, were still genuine peace-keeping missions in which the use of force was mandated strictly for self-defense. This changed in June, 1999, in Kosovo, when Germany participated in the armed conflict against Yugoslavia by both participating in the aerial bombardment and by sending ground troops.

German participation in armed, war-like missions was – by necessity of treaty – greatly expanded, from 2002 onward, in Afghanistan, where major combat operations took place in the greater Kunduz area in Northern Afghanistan, from 2009 to 2011. An epidemiological study conducted by the Bundeswehr, between 2010 and 2013, showed for the first time, empirical data on the quality and quantity of combat related stressors and the attendant psychological sequelae [1]. The potentially traumatic events, as related by deployed returnees in this data-set, were broad and varied. They covered a spectrum straddling the perceived roles of the victim of hostilities to that of a perpetrator of violence (albeit not in the legal sense), for instance when expending lethal fire in an actual combat situation. Having had these experiences significantly increased the odds to sustain posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), at a later time.

Litz et al. [2] showed that this kind of experience of oneself as “perpetrator” could give rise to further maladaptive mental processes. Specifically, they may lead to pathological dissonance with a soldier’s internalized values and norms for behavior. This, in turn, may lead to negative evaluations of said experiences and behaviors which can, finally, amount to incapacitating moral injury, a condition related to but separate from PTSD.

Nash et al. [3] further distinguished between moral injury caused by a soldier’s own acts or omissions and the moral consequences of acts by moral paragons such as military and political leaders. They crafted these two concepts into their own psychometric instrument for the assessment of moral injury (the Moral Injury Events Scale). Unprocessed moral injury can lead to intense feelings of guilt and shame and may even initiate self-destructive behavior such as suicidal acts or substance abuse. This sequence of events and its dangerous end results were scrutinized especially closely in American soldiers who were involved in sanctioned killings in war [4 - 6].

Viewed differently, however, the deployment of soldiers to foreign theaters of war with their inherent traumatogenic potential may also induce psychologic resources and initiate positive mental change such as processes of personal growth and development. On this Tedeschi und Calhoun [7] developed the construct of “posttraumatic growth”, stating that after overcoming traumatic and life changing experiences, positively connoted changes in perception and action may occur. People experiencing posttraumatic growth describe greater appreciation of life, a post-materialist change in priorities, a tendency to warmer and more intimate relationships, higher mindfulness, a better sense of personal strengths, the recognition of new possibilities, and other benefits.

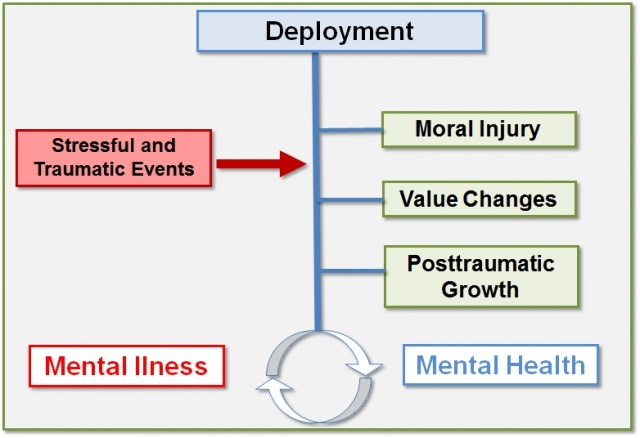

Pict. 1: Dimensions of psychological and moral changes in deployed soldiers

Pict. 1: Dimensions of psychological and moral changes in deployed soldiers

To better understand the underlying causes and moderators of the described pathogenic as well as salutogenic processes a number of studies concentrated on personality based variables such as personality traits, personality disorders, hardiness, optimism, religion and individuals’ values and normative orientations. Values, in particular, are “desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person”. Schwartz [8] developed a comprehensive theory of human value-orientations comprehensively categorizing values into ten different value-types in order to depict values-based perception and behavior in people. It is a hallmark of this theory that it allows for broadly opposing values-positions in one person, for instance a materialistic, pleasure-seeking orientations (the value-type of Hedonism) can exist concomitantly with and opposed to more altruistic, community-oriented values (e.g., the value-types of Benevolence or Universalism). The construct thus lends itself to a circumplex model structure for the ten possible value-types which Schwartz unites in his 40-item self-report survey, the Portrait Values Questionnaire [8]. Like with the moral injury concept, recent studies could show stable associations of certain value-types with clinical variables of mental health, resilience, and psychiatric disorders, among others also in deployed military personnel [9].

Military deployments abroad are uniquely suited for the generation and empirical testing of hypotheses on moral injury, value orientation, and mental health as they predictably lead to defined situations of extreme stress which can alter value positions and deeply held moral tenets in complex ways. However, strictly quantitative approaches are only of limited use in the description and assessment of the processes involved here. They can order, categorize, and to an extent, quantify values or moral perceptions and the experiences that affect them. But they fall short of capturing the various otherwise detectable influences, evaluations, and internal reparatory processes that take place in affected individuals.

At that, there is a remarkable lack of well executed qualitative scientific research on this topic, especially in the military context. This is partly owed to the fact that the various national militaries deployed in international forces with their specific cultural backgrounds and their own military traditions operate at different local threat levels and have vastly different experiences in their respective theaters of war which in turn will give rise to a plethora of divergent mental and psychologic reactions in their respective personnel.

It is hence the object of the present observational study to qualitatively examine the association of moral injury, value orientation, mental health, and the attendant psychological coping processes in a sample of German soldiers, in-patients treated for psychiatric disorders in an open psychiatry-psychotherapy ward of a German Armed Forces Hospital. The overall goal of the present study is to contribute significant new hypotheses and to promulgate an empirically based program for future military medical research on the intersection of values, combat, and mental health.

Methods

The data for qualitative processing was generated from ten focus groups with a total of N = 78 participants (that is, six to nine participants to each group). Participants were, exclusively, active service, male, German Armed Forces soldiers who had participated in one or more military deployments abroad as part of the International Security Assistance Force’s (ISAF) mission in Afghanistan. All were on in-patient status at the German Armed Forces Hospital (GAFH) Berlin on account of a deployment-related psychiatric problem. Mean age was 34 ± 9 (SD) years. In 54 of the participants, PTSD was diagnosed, in 29 a deployment-related depression; in 28 an adjustment disorder; 10 suffered from somatoform symptom disorder or pain disorder; 12 from anxiety disorder; 13 from various other psychiatric disorders (multiple answers were possible).

Focus groups were conducted in the initial phase of a three-week behavioral group-therapy regimen offered at GAFH Berlin, quarterly, to improve symptom control and resources for symptomatic soldiers after deployment. The groups were primarily therapeutic in design and intent. Since all data gathered was used to direct treatment planning and scientific evaluation thus being an intangible side-benefit we could forgo the assessment of this study by an institutional ethics committee.

Besides clinical need the other main inclusion criterion of patients into the group and the study was their ability and willingness to discuss the topic of the focus group. Excluded were those who in the preparatory interview expressed anxiety or showed high emotional stress in relation to the topic. Groups were conducted as dual moderator focus groups by interviewers well versed in focus groups, with completed training in psychotherapy and psycho-traumatology as well as multiple years of relevant professional experience. Each group session lasted for 90 to 120 minutes, was electronically recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis was performed following the standard for qualitative contents analytics by Mayring [10]; the interview structure was developed as a template of leading questions using deductive category evolution. To this end we used the theoretical models underlying our initial hypotheses, namely Schwartz’s personal value orientations [8] as refined by our own previous quantitative studies using the Portrait Values Questionnaire to detect associations of value types and psychiatric disorders [9]. Furthermore, we included the moral injury construct according to Nash [3] and its causative model as expounded by Litz [2] to capture the relationship between moral injury, guilt, shame, and psychiatric disorders. The study design allowed for inductive adjustment of the interview template as the need emerged.

Overall, the interview template covered the following topics as represented by these five leading questions:

- During your deployment, were there situations or events which challenged your own personal values or which attacked your moral sensitivity?

- Which of your own personal values have changed during the course of your deployment or even in the time after, as noticeable to you or your loved ones?

- Which psychological or social consequences and which physical and mental symptoms have you experienced during deployment?

- Which psychological or social consequences and which physical and mental symptoms in relation to deployment-stress have you experienced after your return from deployment?

- Which strategies or techniques did you use to help you get over the effects of what you went through?

Results

The focus groups we conducted were well able to approach the topic of this study freely and unencumbered. Participants related their experiences in a genuine fashion. Afterwards, they expressed that dealing with their experiences in this way was new to them but that it had felt helpful. Throughout, certain emergent, negative emotions such as anger, disappointment, or similar feelings proved to be addressable and manageable.

Situations or events during deployment which impacted on value orientations or caused moral injury

Regularly, group discussions set out with renditions of certain significant, value-relevant, and stressful deployment experiences, such as:

- encountering an alien culture with different (read: repulsive) apparent values and norms;

- realizing the supreme value placed on traditions, customs, and certain religious practices by indigenous populations;

- experiencing a participatory and more permissive modus operandi within one’s own deployed contingent, resulting in flatter organization, de-emphasis on military hierarchy, and broader personal discretion;

- witnessing mistakes made by superiors resulting in unsuccessful operations or dangerous situations;

- realizing own mistakes resulting in unsuccessful operations or dangerous situations.

Encountering the culture of the host country was accompanied by a more or less intensive experience of its value system and behavioral norms – the intensity being largely dependent on the type of operational specialty and military activity. Specifically, the treatment of women and children was frequently described in negative terms as discriminatory or even violent: “Women and children count for nothing down there; they are treated like shit and get discarded once you’re through with them”.

The differences were also able to be appreciated by some: “In the desert a bottle of water is worth a lot. I am still having a hard time to just let drain any extra water since I know how much it is worth down there“. The use of traditions, customs, and religion is seen as part of the indigenous culture in the broader sense. The deeply rooted behavior of the indigenous population was thus perceived by participants as both impressive and overly constricting in its immutability, which also made it fearsome and intolerable.

As regards the own military structure and organization, some three quarters of participants experienced the flatter hierarchies within their deployed contingent as an improvement strengthening their autonomy and their discretion of action. They felt an increased appreciation and self-worth which led to much better identification, task-ownership, and meaning-making: “Down-range, we’re all equals. We sit down together, eat together, we all talk at eye-level. That’s much different from back here, at home.”

Various other experiences of deployment were rated to be of momentous impact on one’s own value structure. The constant threat to life and limb had led in many to an anxious and volatile sense of uncertainty where one’s safety and well-being had lost its reliable presence. Conversely, this experience strengthened the appreciation of normalcy and health: “I could have died down there, anytime. Today, I think about death much more than before deployment, but I cherish each single day much more intensely.”

About one third of respondents took exception to their superiors’ actions. While many also found praise for model behavior, a focus on poor performance was prevalent. Superiors whom they had tended to lionize during pre-deployment training were now judged as out of their depth. This was partially attributed to poorly crafted orders that paid too little heed to the safety of subordinates: “Here they go, just sending us out to reconnoiter an IED [improvised explosive device], knowing full well that the thing could blow up on us, any second!”

To this some added accusations that their superiors would take no real interest in their subordinates and that they merely wanted to avoid mistakes in order to protect their careers. This could lead them to defer important decisions. Also, support and appreciation by superiors were judged to be rather too weak.

Conversely, the discussion of their own morally insufficient actions was also lively among participants. It centered on self-doubt and negative appraisal of one’s own action in certain critical situations where one had not handled oneself professionally or courageously enough or had not helped others sufficiently. This was more prevalent vis à vis the problem of civilian poverty, especially among children, in cases of severe traffic accidents with fatalities, or when violence among the population was observed: “We once had to witness the stoning-to-death of an adulteress. We just happened upon the scene and we were ordered not to intervene so as not to provoke unrest in the village.”

Peculiar concern was voiced around the necessity to kill or wound others (by about one fifth of participants). This could lead to internal conflict, among other things, in relation to one’s own humanitarian or Christian values and beliefs. Equally difficult was the experience of not being able to prevent a killing, for instance when buddies were killed in action or when collateral civilian casualties occurred: “At one time, the ANAs [Afghan National Army soldiers] wiped out an entire village where they thought there was Taliban. There was nothing we could do. Afterwards, I saw all those dead bodies. I had to vomit.”

Grafik hier einfügen[h1]

Change in Value Orientation under Deployment

Three quarters of participants reported that their personal value orientations had changed during and after deployment. In part these soldiers had detected the changes themselves, in some others they were noted by loved ones. Changes fall into these nine main categories:

- decreased estimation of material possessions;

- increased estimation of immaterial goods;

- increased estimation of buddy-to-buddy relations and of private obligations from family and friends;

- increased care for buddies, especially from common deployment;

- increased care for family;

- increased estimation of control, structure, order, and sense of duty;

- increased estimation of sports as a source of self-worth;

- development, or where previously present, increase in religious and philosophical involvement;

- emphasis on hedonistic goal-orientation.

In general, there emerged a less compromising and more intentional stance in the adherence to one’s own value orientation and in living by one’s own norm system. Many soldiers reported they had set out on deployment harboring a rather more materialist value orientation, directed for instance on the purchase of a more expensive car by way of their high foreign deployment pay. At the end of their deployment, they had a much dimmer view of the personal gain from such a purchase. Rather, they found that immaterial values had gained prominence in their values hierarchy, values such as closeness to their core family and to friends, their own partners and children, and their local community of origin. One participant remarked: “Previously, only my car counted. After deployment, I realized how much my girl-friend meant to me; that has really improved our relationship.”

In most cases, this value change was paralleled by a strong increase in the estimation of military companionship, the cohesion with and feeling of mutual responsibility for one’s immediate buddies. This feeling extended to the newly trained, never-deployed fellow soldiers whom respondents wanted to support to become fully trained and prepared. On the other hand it was mobilized as a shared sense of obligation and commitment, often over a period of many years, to the buddies from one’s own deployment. And it could even take the form of tangible assistance and help in emergencies. A combat soldier from an armored infantry (Panzergrenadier) unit put it this way: “Ever since these guys from Charly Unit saved my ass that day, they have become real close to me. I will never forget what they did for me. They can always come to me for, whatever, ask me for anything!”

The intensified, more closely held family ties resulted in some (about one tenth) of respondents in increased control and safety concerns. This showed more strongly in their relationships with their children and was liable to be perceived by loved ones as being constricting and overprotective. One combat soldier told us how he observed himself closely regulating his own son and denying him any unsupervised activity which led increasingly to arguments.

In three cases, participants reported an increase in hedonistic pleasure-seeking: “After deployment, I lived like there was no tomorrow. It was all sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.”

Religious and philosophical involvement increased, although more rarely (in about one tenth), but around two thirds of soldiers related that they now expressed and lived their value positions more consciously and, at times, more rigorously than before their deployment. On this, a military transport specialist shared: “I was involved in a lot of combat, during my deployment. Every small mistake could have cost me my life. Since that time, I react much more harshly to my buddies’ mistakes. I know what it could cost you.“

Psychological and Social Sequelae and Reactions to Deployment by way of Changes in Value Orientation

In this area of assessment, we found participants reporting changes, both during deployment and after their return.

The sequelae and reactions during deployment were:

- compassion and sympathy for the suffering of the indigenous population, feeling of helplessness;

- the urge to render assistance and to engage in humanitarian projects;

- protection from and defense against intolerable emotional stress;

- a feeling of senselessness and futility of the deployment;

- rage against the indigenous population;

- distrust of newly arrived, unexperienced military personnel in one’s area of operations.

Negative attitudes (most of all anger and disappointment) towards the civilian population was voiced by about half of all participants, at times combined with feelings of shame about those attitudes. The reason for this was often the observed violence perpetrated against their buddies or against indigenous women and children. This anger was frequently cloaked in pejorative monikers for the indigenous population (“Klingons”, “Blackfeet”). On top of this, we detected emotions of rage and a sense of futility in the face of reports of opposing forces (Taliban) regaining certain positions after the ordered withdrawal of German troops, such as was the case with the former German field camp in Feyzabad.

An opposite reaction was shown as being a strong emotional bond with the civilian population and their suffering. One Military Police soldier who was on patrol a lot in Afghanistan told us: “After a while, I couldn’t bear the wretchedness anymore. I joined Lachen Helfen[1] and was actually able to contribute to a number of good projects. Among other things we furnished a school with school supplies. That really made me feel good.”

Yet others reported to have been able to protect themselves from the emotional stresses that contact with the indigenous population carried by limiting such contact to the absolute necessary minimum.

Also after return from a deployment abroad, there were a number of psychological and social sequelae that came to light in the group discussions and that were difficult to distinguish from symptoms of psychiatric disorders. In an attempt to become more specific, we had group members discuss which ones of the changes they would attribute clearly to changes in their own value base.

Specifically, these reactions emerged after return from deployment:

- a more skeptical attitude towards their superiors at home;

- feelings of aggression and impatience toward their buddies and superiors;

- experiencing the time of their deployment as the only „real reality”, combined with a yearning to go back;

- taking pride in their unique experience and having a feeling of supremacy over fellow soldiers without missions abroad, also over the German civilian population in general;

- a feeling of being alienated from previous social ties at home;

- a general disposition of mistrust or a feeling of not being understood;

- disappointment and bitterness, particularly vis à vis the German Armed Forces (Bundeswehr);

- increased general tension;

- somatoform symptoms.

A broadly shared tenet among previously deployed soldiers was that their deployment was “the real deal”, in spite of all its mental and physical hardships, combined with a desire to be sent back downrange, soon (so called „mission junkies“). As one combat soldier put it: “It was all so intense, so much a part of me – life at home just seems pale and phony in contrast. I wish I could go back!” This feeling after returning to Germany was frequently associated with an experience of being estranged from one’s prior frame of reference within the military unit or within one’s family and friends. Vis à vis superiors this resulted in a more skeptical stance as the reentry into proper chain of command and homeland routines, the exigencies of bureaucracy, and related phenomena led to substantial anger, especially with fellow soldiers of higher rank who had done no combat missions abroad. “I regarded those superiors who had never been deployed as weaklings, couldn’t take them serious. When they would give me an order, I would mostly comply but show my resistance clearly.”

This process of estrangement was not always combined with adverse emotions. In some cases soldiers expressed significant pride in their accomplished change. They based this on their success of having mastered challenges in their deployment that did not even exist at home.

On the symptom level participants mostly reported feelings of being misunderstood, emotions like aggression, distrust, disappointment, and bitterness. The latter two sentiments came about especially under conditions of a denial of applications or entitlements (e.g., of military disability, WDB in German). One soldier who had done five tours abroad, explained: “When I got the refusal notice on my combat disability application, I felt betrayed. I had gone on deployment for my country for so many times and they didn’t even pay token respect!”

In about one third of respondents there were somatoform symptoms, not all of which were severe enough to qualify as psychiatric. The spectrum displayed was diverse. Frequent were non-specific vegetative symptomatology and chronic pain. A telling example was that of a patient who had a number of healthy teeth extracted because of chronic somatoform mandibular pain; another was that of a soldier who gained about 50 kilograms upon his return, a fact he attributed to his own stress induced eating.

Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping-Strategies

The described consequences of moral injury and changes in value-orientation led to a variety of coping strategies in the afflicted soldiers:

- constructive community participation, partially as charitable community service,

- over-engagement in social and health-related activities;

- altered or skewed new emphasis on planning and managing one’s life, resulting, e.g., in applications for an assignment closer to home;

- separation or divorce from one’s spouse;

- resignation and mental quitting;

- increased need for care and attention with a tendency toward pathological regression;

- inappropriate attempts at „self-medication“ through substance abuse (mostly alcohol);

- incomplete tolerance of and resistance against professional medical or therapeutic offers.

Disappointment associated with superiors or the Armed Forces establishment in general, during deployment, led a few of the soldiers (around one fifth) to feel like they wanted to resign, or mentally quit the service. Those afflicted felt betrayed by the Bundeswehr and refused to exert more than the bare minimum effort in the execution of their home service duty. This would lead, in some cases, to long periods of sick leave, sometimes combined with substance abuse and noticeable auto-destructive tendencies. One combat soldier can be quoted as saying: “I used to be a soldier’s soldier, really gung-ho. Today, I don’t care about the Armed Forces anymore, it’s just a job. I put in the minimum but I don’t enjoy it, I also don’t expect it to change for the better.”

Another group reacted clearly more self-directed and results-oriented. The German Armed Forces offer a wide variety of secondary preventive, pre-clinical measures of assistance for deployment-related injuries and psychologically impaired soldiers. This group had used these offers more than once, before, and felt that they were entitled to them. These soldiers (about one third of respondents) displayed a critical, unsatisfied, and at times demanding attitude toward the German Armed Forces as far as its occupational medical services were concerned. This had in some cases already led to petitions to the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces (Wehrbeauftragter) of the German Bundestag (Parliament) or it had become the topic of negative coverage they elicited in local and national media. Still others had obtained political influence that they used to improve the lot of wounded returnees, or they would join in charity-work such as with victim support and assistance associations.

Redesigning one’s individual life-style was also talked about in the conversations. The renewed focus on family and friends mentioned above led to a desire for an assignment closer to home in order to avoid long-distance or weekends-only relationships (by circa one third of respondents). This was accompanied by a high readiness to accept adverse effects on one’s career: “Now, my family comes first. Previously, I was gunning for General’s stars, but I don’t care for that anymore. I know how important family is to me and all I want is to be with them.”

The opposite reaction was also reported. A substantial group of respondents (one third) had already split from their partner in separation or divorce primarily because their personal changes had increasingly brought about estrangement and distance into the partnership.

Discussion

The present study aimed at using qualitative data acquisition to draw a clear and detailed picture of value-orientations and moral injury associated with deployment-related psychological stresses and psychiatric disorders. Participants were surprised, throughout, by the rapidly building cohesion and the mutual understanding within the groups. This was evident even across rank-tiers and educational strata. We took this to show how value-oriented reflections on deployment have good integrative potential across and beyond social boundaries.

The overwhelming majority of responding soldiers had been exposed to morally injurious events, while deployed, and showed moral injury. At the time of this study, it being removed in time from these events by up to several years, the events still felt considerably present and had brought about a diverse range of reactions and changes. Prominent among them was a change in personal values implying both positive and negative consequences. This change would frequently impede their readjustment to social circumstances and roles at home, in both private and service environments.

Furthermore, we frequently detected strong ties between moral injury and psychological stress up to and including psychiatric disorders. We could not find any stereotypical patterns hinting at a generalizable association of injurious event, psycho-social reaction, and – as the case may be – mental illness. Sundberg [11] already indicated that the specific interaction of an adverse event in a military theater with an individual’s value system must be the stronger determinant of any possible sequelae than the nature of the event itself. On the other hand, a number of studies in the military context show statistically detectable associations of the related factors. For instance, killing an opponent would regularly worsen the symptoms of subsequent posttraumatic stress disorder and could lead to depression, suicidal ideation, or substance abuse [4 - 6]. In addition, a correlation was established between combat participation frequency and the likelihood of perpetrating acts of cruelty and war crimes [12]. These acts were not covered at all by the present survey which may be explained by the different deployment reality facing German soldiers.

In a recent survey study of close to 200 German soldiers at the end of their tour in Afghanistan, we showed an association between adverse experiences during deployment and moral injury or psychiatric disorders, respectively. Those associations were most significant with stressors involving the indigenous civilian population such as acts of violence among them, directed hostility, etc. (Hellenthal et al.: „Einsatzerlebnisse, moralische Verletzung, Werte und psychische Erkrankugnen bei Einsatzsoldaten der Bundeswehr“ [Deployment experience, moral injury, values, and mental illness in deployed German Armed Forces soldiers], manuscript in preparation by our group). Using Nash’s [3] conception of moral injury, we found that the most frequent of these injuries followed an egregious deviation from moral principles on the part of moral authorities such as superiors. Experiencing this was, in turn, significantly associated with symptom severity of PTSD, depression, and alcohol abuse.

In two recent publications on deployed soldiers three to six months after returning, we could show links between certain value-orientations and symptoms of mental illness. For Instance, the value-types of hedonism and stimulation-seeking rendered posttraumatic syndromes such as PTSD less frequent and less severe, while the values of universalism, tradition, and benevolence lead to more serious forms of illness [9].

In the same vein, the findings on change in value-orientation through the effects of combat deployment remain inconclusive. Sundberg [11] could not detect any meaningful change of values – as assessed by the Portrait Values Questionnaire – in 320 Swedish soldiers whom he examined before and after a six-month tour in Afghanistan. He found, however, a significant, if weak, association between combat participation and value-change phenomena. Conversely, a study of young Israeli civilians, during the 2006 Lebanon War, showed clear changes in values [13]. Also, Bardi [14] established a link between stressful life-events and the test-retest reliability of values-related assessment instruments which suggests an influence of external variables on values.

Further support of the idea that adverse experiences in war change values came from research on 7,500 World War II veterans by Wansink et al. [15]. They showed that veterans who were involved in heavy combat during the war and who rated their war experience negatively were significantly more likely to go to church and to frequent religious ventures than their peers who appraised war rather more positively.

It is conceivable that the diversity of findings we are facing is an artifact of the two main methods employed: quantitative and qualitative surveys and assessments. Quantitative methods are more easily standardized across samples and testers. But they are also limited in their scope and cannot elucidate all potential causal relationships between variables which reliably turn up in qualitative interview data.

Still, one important tenet of the data and results presented here was much in agreement with previously published findings. The uncovered positive changes connected to combat deployments abroad fit well with the concept of posttraumatic growth according to Tedeschi and Calhoun [7]. It describes a desirable development in recovered traumatized individuals that kindles increased reflexion and improved personal meaning-making. That overcoming trauma is leading to a more intense appreciation of life, of personal relations, and of individual strengths was similarly evident in the present study.

Limitations

The evidentiary power of the present study is limited by a number of known factors: Respondents were recruited selectively from a clinical sample of patients with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Therefore, its results can only be transferred with care to the total of deployed soldiers. A further selection bias could have arisen from the inclusion criterion of sufficient willingness to verbally express themselves about this sensitive topic.

On the upside, using the diverse and quite candid reports of our respondents we were given a broad yet detailed depiction of many deployment related stressors which must also take a heavy toll on many combat soldiers who never get sick. To verify this hypothesis, additional focus groups using similar leading questions should be conducted with ostensibly healthy combat soldiers.

It did pose a methodological challenge to ascertain that the observed changes in value-orientation were in truth related to the reported morally injurious events. Cleanly separating cause and effect when dealing with these processes will remain difficult.

Conclusion

The results we obtained from this qualitative observational study show a broad yet detailed depiction of value changes and moral sequelae following foreign deployment of German Armed Forces soldiers and their links to psychiatric disorders. Moral injury and changes in value-orientation have the potential to cause great psychological suffering and to amplify the effects of parallel stressors of war. It is therefore a reasonable demand that more emphasis be put on these aspects of deployment-stress, both in the return-processing of soldiers, in military psychiatry treatment regimens, and in future preventive pre-deployment training elements aiming at “moral fitness”. Initial, novel approaches in military psychiatry have already begun to include moral injury and value change concepts into the psychotherapy (group) treatment settings in German and US soldiers with deployment-related mental illness [16]. Further evaluations and the expansion of similar programs are being planned.

Core Messages

- Psychiatric disorders in deployed soldiers are often associated with moral injury and changes in value-orientation.

- Causal agents are intercultural incompatibilities of deployed contingent and indigenous populations as well as structural shortcomings within the military contingents themselves.

- Some psychological sequelae already show up during deployment, but most appear after the return home.

- Coping strategies of the afflicted are many and diverse; they span the full range from assertive posttraumatic growth to auto-destructive mechanisms.

- The topic should receive more attention when further preventive and therapeutic concepts are developed within the German Armed Forces (Bundeswehr), in the future.

References at [email protected]

Citation:

This article was first published in the German Armed Forces Jounal “Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 2016; 60(1): 7-14“.

Authors:

Colonel (MC) Dr. Peter Zimmermann

German Armed Forces Hospital

Bundeswehrkrankenhaus Berlin, Psychotraumazentrum

Scharnhorststrasse 13

10115 Berlin, Germany

Email: [email protected]

First and corresponding author

Co-Authors:

Christian Fischer

German Armed Forces Protestant Clergy HQ

Sebastian Lorenz

Christina Alliger-Horn

German Armed forces Hospital Berlin

Peter Zimmermann1, Christian Fischer2, Sebastian Lorenz1, Christina Alliger-Horn1

[1] The private German charity „Lachen Helfen e.V.“ is a project launched by German soldiers and police to benefit children in theaters of war: www.lachen-helfen.de.

[h1]OBEN HATTEN WIR Das schon einmal in Englisch – es gibt aber nur eine Graphik, deren Platzierung sich mir nicht erschließt. Wie sieht das denn im Original (WMM) aus?

Date: 03/24/2016

Source: MCIF 2/16