Report: J. M. MULVEY*, A. A. QADRI†, M. A. MAQSOOD†

Earthquake Injuries and the Use of Ketamine for Surgical Procedures

The October 8, 2005 earthquake in Northern Pakistan had widespread destructive effects throughout the northern subcontinent.

Large numbers of people were killed or severely injured and many medical services destroyed. This report describes the experience of the only standing surgical hospital in the Kashmir region of Bagh District. More than 1,500 people were triaged in 72 hours, many critically injured; 78.4% of patients had upper or lower limb injuries; 50.3% of patients had fractures, mainly closed; 37% of patients required extensive wound debridements. A total of 149 patients received emergency surgery using ketamine anaesthesia with benzodiazepine premedication. This was found to be safe, effective and with a low incidence of major adverse effects. We recommend that ketamine anaesthesia be encouraged in disaster area surgery, particularly in under-resourced regional centres.

On October 8, 2005, an earthquake in Northern Pakistan triggered mass destruction to the regions of Northern Pakistan, Azad Kashmir and Northern India. Measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale and occurring in the mountainous terrain of the Himalayan foothills, many houses and buildings (including government hospitals) collapsed, resulting in death, injury and loss of property. With more than 86,000 people dead, over 80,000 severely injured and up to 3.3 million people displaced without adequate shelter, this earthquake devastated a region already stretched for adequate resources. The United Nations Chief of Emergency Services has declared this disaster the worst in history, including the 2004 Tsunami.

Occurring at 0850h local time, children were killed or injured attending school and adults were killed in the home and workplace. Although not sustaining the worst of the earthquake damage, the Kashmir region of Bagh District (covering 1,368 km2) suffered 8,157 deaths, 6,644 people badly injured and 65,704 houses destroyed. All major hospitals except one were destroyed. This hospital, in Forward Kahuta (FK), had its first patient 10 minutes after the quake and over the next 72 hours saw more than 1,500 patients. Although not all of these needed surgical intervention, a large number of these patients were operated on in medically challenging conditions, in a hospital with minimal staff, minimal monitoring modalities and limited facilities. Nevertheless, there was a good surgical success rate.

This is a descriptive review of patients who were given ketamine as the anaesthetic agent of choice for emergency surgical procedures at the Mobile Surgical Team (MST) military hospital, Forward Kahuta (FK), Kashmir, in the first 72 hours after the 2005 Pakistan earthquake due to quake-related injuries.

MEDICAL EQUIPMENT AND FACILITIES

FK is a small town near the Line of Control between Indian-held Kashmir and Pakistani-held Kashmir. It is the capital of the Haveli subdistrict, in the foothills of the Himalayas. The subdistrict has 98 villages, with an area of approximately 450 km2 and a population of 140,000 people. Most of these people live in mountain villages with steep terrain, poor road access and little public transport.

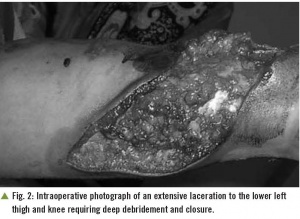

Intraoperative photograph of an extensive laceration to the lower left

thigh and knee requiring deep debridement and closure.

Intraoperative photograph of an extensive laceration to the lower left

thigh and knee requiring deep debridement and closure.

The medical facilities present in the Haveli subdistrict are comprised of a small government hospital, a MST military hospital, approximately 16 basic health centres and various first aid posts (military and government). Only these two hospitals are capable of offering acute surgical care. Cases needing urgent referral are sent to the district capital of Bagh, approximately three hours by car, or to the Pakistan capital of Islamabad, approximately seven hours by car.

The FK MST was the only surgical facility left functional in the affected Kashmir region after the October 8 earthquake. No outside help was available from the government or military, including emergency evacuations, for 72 hours. This was because higher priority areas were attended to first and also temporary loss of communications. FK MST medical staff included a surgical specialist, an anaesthetist, a medical specialist, a pathologist, two general practitioners and limited paramedical staff. There were twelve beds in the hospital, one operating theatre, one minor procedure room and a basic sterilizing facility. Due to its unreliable supply of electricity, the MST is often reliant on a power generator The primary function of the MST is to provide medical and surgical care to the Pakistani military personnel deployed in the region and free health care to the Kashmiri civilians.

TRIAGE

Patients were assessed and triaged by the pathologist and regularly reviewed by paramedical staff. Patients were assessed at the front of the hospital; those less critical were sent onto the roof and those severely injured allowed to proceed into the hospital. Patients deemed to be urgent were reviewed by the anaesthetist, intravenous (IV) resuscitation fluids were commenced and the case was discussed with the surgeon.

Patient demographics

Approximately 1,500 earthquake-related casualties were received at the FK MST. Of these, 468 patients required admission and active surgical management, while 149 required anaesthesia for urgent surgical intervention. The data in this paper relates only to these 149 patients, all of whom received ketamine.

The mean age of patients was 26.7±15.5 years (range 5 months to 70 years). Forty-eight patients (32.2%) were younger than 20 years; 13 patients (8.7%) were 50 years or older and only one of those was greater than 70 years; 87 patients (58.3%) were male.

Injuries at presentation

One hundred and thirty-three (89.2%) patients had a single anatomical site injury, while 16 patients (10.8%) had multiple injuries. The majority of injuries were to the upper and lower extremities (78.4%), with injuries to the head (8.2%) and back (5.6%) being the next most common.

A total of 75 patients (50.3%) presented with fractures, five (6.6%) of those with an open injury. 18 patients (24.0%) had multiple bones fractured. 56 patients (37.0%) required extensive wound debridement. There were 10 (6.7%) patients with limb dislocations, six (4.0%) degloving injuries, five (3.3%) traumatic amputations and four (2.6%) penetrating abdominal injuries. Of the total orthopaedic injuries, 71.0% were closed fractures.

Fluid requirements

IV fluids were administered prior to surgical intervention. Fluids used included Ringers Lactate, Hemaccel (Hoechst Marion Roussel), 2.5% dextrose with half normal saline and whole blood. Due to a paucity of blood supplies, only patients with excessive blood loss intra-operatively, increased pallor, or a significant history of blood loss at the time of injury (as deemed by the surgeon) received whole blood.

All patients received crystalloid fluids with a mean volume administration of 2.09±0.87l (range 0.3 to 3.5l). Eight patients (5.3%) received colloid fluids as a single administration of 500 ml. Six patients (4.0%) received whole blood, limited to one unit (500 ml) per patient.

ANAESTHETIC TECHNIQUE AND MONITORING

Monitoring modalities for the entire hospital were limited to three manual blood pressure cuffs, one oxygen saturation monitor and one electrocardiogram. Patients needing surgical procedures were reviewed regularly by paramedical staff. Due to the lack of monitoring equipment, staff called out pulse rates at regular intervals to the anaesthetist. The anaesthetist conducted a round between cases to identify and prioritise the most critical patients.

All patients were required to have a minimum of 3.5 hours of postprandial fasting prior to surgery. Due to the Islamic tradition of fasting during the month of Ramadan, which by chance occurred during the quake, most patients were fasting since sunrise. Patients and carers were advised not to eat while waiting for surgery, particularly at night when Ramadan fasting would cease. The average fasting period was 6.76±1.93 hours (range 2 to 13 hours). Unbeknown to the staff, one patient had eaten two hours prior to surgery, despite the carer repeatedly being told of the importance of fasting.

All patients were premedicated with IV diazepam 0.1 mg/kg to blunt the cardiovascular response, for its anxiolytic and amnesic effects and to reduce the amount of ketamine required for surgery. All patients were then given an initial IV ketamine dose of 1.5 to 2 mg/kg slowly over 60 seconds approximately five to ten minutes prior to procedure. Repeat dosages of 0.5 mg/kg IV were given for prolonged procedures or inadequate dissociative anaesthesia. Up to five patients were anaesthetized simultaneously for surgical intervention.

Thirteen patients (8.7%) needing intubation and muscle relaxation were given suxamethonium 0.5- 1.5 mg/kg IV and pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg IV. Of these, four patients (30.7%) were routinely intubated for laparotomies, three (23.0%) due to full stomach, two (15.4%) due to their young age (less than one year), two (15.4%) due to increased intraoperative vomiting and one (7.6%) due to persistent laryngospasm and the need for muscle relaxation.

If positive pressure ventilation was needed, a hand bag-mask technique was used, as there was no mechanical ventilator; otherwise patients breathed spontaneously with simple manoeuvres used to manage the airway. Oxygen was used sparingly only for those demonstrating hypoxia as determined by pulse oximetry. Patients were recovered in a lateral position postoperatively and reviewed for 20 to 30 minutes by the paramedical staff for complications.

Only major adverse events of ketamine anaesthesia were looked for and recorded. These included vomiting, laryngospasm and hallucinations. Hallucinations were reported subjectively by the paramedical staff as behavioural disturbances outside the context of injury and pain. Unfortunately, due to the circumstances, subtle emergence phenomena were actively identified.

Operations

Despite the presence of one theatre operating room, necessity required that some patients had their procedures performed on tables in the hallway outside the operating theatre. This was mainly for fractures and simple debridements. The average length of procedure was 22.4±12.0 minutes (range 10 to 90 minutes).

There were 82 (54.3%) fracture manipulations. Open fractures were thoroughly washed with saline and primarily closed. No internal fixation devices were used due to poor supplies. If required, external fixation hardware was utilised. Fracture positioning was checked only postoperatively as there were no intraoperative radiology facilities. There were 56 (37.0%) wound debridements.

Four (2.6%) laparotomies were performed. There were three large bowel perforations and one small bowel perforation. All these injuries were managed with oversewing. No portions of bowel were removed. There were no splenic, hepatic or renal injuries. Eight patients (5.2%) required limb amputation. One patient required a chest drain for a penetrating injury.

RECORD TAKING AND PHYSIOLOGICAL DATA

Due to time constraints and situational requirements, preoperative haemodynamic information was not recorded. Paramedical staff relayed preoperative vital signs to the anaesthetist verbally, who reviewed and managed the patient accordingly. Intraoperative information was recorded in a limited fashion only after the commencement of an IV resuscitation fluid bolus. This was limited to age, gender, injury, post-prandial period, IV fluid requirements, initial intraoperative observations (pulse rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation), ketamine dosage, intubation status and complications.

Ketamine related complications

The major adverse effects of ketamine were recorded in a ‘yes/no’ fashion, with the extent of the adverse event reported subjectively. By necessity, minor adverse reactions were not identified or recorded.

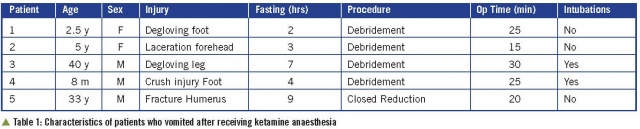

There were no antiemetic medications available. Five patients (3.3%) experienced intraoperative vomiting. Two of these patients (40.0%) were intubated to effectively manage the airway. There was no obvious association between age, gender, postprandial period, procedure, or procedure length. The characteristics of these five patients are outlined in Table 1.

No patient experienced a decrease in oxygen saturation (<90%) or developed aspiration complications postoperatively. All were suctioned effectively and, if possible, were rolled into the lateral position. In patients who could not be placed in the lateral position due to the surgical procedure, the airway was actively suctioned and secured with endotracheal intubation.

It should be noted that one of the patients who vomited, a child of two-and-a-half years, was fed two hours prior to the procedure. When questioned, the child’s carer stated that she was concerned her infant would starve to death if not fed while waiting. However, this information was only obtained after the child had vomited during the anaesthetic.

Two patients experienced laryngospasm. One patient required suctioning and simple airway manoeuvres to improve air entry and relieve spasm, while the other patient required suctioning, muscle relaxation and intubation. Neither patient experienced significant decreases in oxygen saturation (<90%) during the episode.

None of the 149 patients experienced hallucinations, either intraoperative or in the immediate postoperative period.

POSTOPERATIVE PAIN AND DISCHARGE

Stretched resources, both in terms of bedding facilities and pain medications, limited the extent to which care was given in the postoperative period. If deemed haemodynamically stable, patients were discharged immediately following recovery from ketamine regardless of their pain levels. Unfortunately, the conditions at the time and the ever- increasing number of injured people presenting for assessment and treatment meant that only the sickest could occupy one of the twelve beds, with often as many as four critically unwell per bed.

No IV analgesia was available and ketamine was not administered for postoperative pain as it was unclear how much ketamine would be needed for surgical procedures alone. Patients were discharged with twelve tablets of paracetamol 500 mg alone, or in combination with codeine phosphate 30 mg. Patients were also given a prescription for analgesia as the local pharmaceutical dispensary was functional, although it also had limited stocks.

Of the patients receiving ketamine for surgical intervention, no deaths were reported either in the intraoperative or immediate postoperative period (up to four days—verbally communicated via village elders). Only two patients (of the approximate 1,500 patients) who presented to the hospital in the first 72 hours died. Both mortalities were due to severe head injuries and little could be done to help them because no retrieval service was available to relocate them to a tertiary centre that could provide necessary neurosurgical support.

Characteristics of patients who vomited after receiving ketamine anaesthesia

Characteristics of patients who vomited after receiving ketamine anaesthesia

DISCUSSION

Earthquakes of the magnitude experienced in Northern Pakistan and Azad Kashmir create a challenging environment for medical facilities in disaster management zones. As seen in the 1999 Marmara earthquake, emergency departments were swamped with large numbers of patients in the immediate post- quake period. Up to 26 hospitals were destroyed or non-functional in the Northern Pakistan and Azad Kashmir region, placing additional pressures on an already stretched system.

Medical management after an earthquake includes search and rescue operations, emergency evacuations and immediate assistance from nearby services. In Azad Kashmir, the complexity of the situation, including the destruction of multiple hospitals, roads, landslides, loss of communication and the huge numbers of injured patients, meant that functional hospitals had to manage unassisted for many days under difficult and trying circumstances.

In the FK region, 19,240 buildings collapsed, including schools, the governmental hospital, military compounds and houses. The number of collapsed structures can be related to the poor quality of single and multi-storey buildings, the lack of practice codes, and the high incidence of mud-brick housing. As in other developing countries, mud-brick houses often have weak walls with a heavy ceiling and readily collapse as a result of significant seismic activity, inflicting severe head, chest and abdominal crush injuries leading to death. It has been suggested that up to 80% of people die in a single-storey building collapse and importantly, the type of materials used for construction greatly influence mortality and morbidity.

The FK MST remained functional after the October 8 quake, seeing approximately 1,500 patients in first three days. Of these patients, 31.2% needed acute surgical admission for a variety of injuries. Of the injury data presented in this paper, the majority were from orthopaedic injuries, mostly closed fractures of the extremities. Minimally invasive techniques were used and, under these circumstances, are well recognised to reduce the likelihood of infection. Regardless of procedure, all patients were given daily IV ceftriaxone to decrease infection rates and, at the time of writing, few patients had presented to follow-up with wound infection.

In this study, anaesthesia techniques were limited by pre-quake supplies, the paucity of available monitoring devices, a large critical patient load and minimal staffing. While ketamine is rarely used in Pakistan, and is often actively discouraged, it was used as the general anaesthetic agent for emergency surgery during this earthquake disaster. Ketamine was chosen as a parenteral anaesthetic agent due to its well documented favourable properties, including absence of respiratory depression, preservation of airway reflexes, low incidence of both hypotension and bradycardia, as well as its relative safety without advanced anaesthetic machines and patient monitoring devices. It has a wide therapeutic range, is cardiovascularly stable and has a rapid onset of action and short half-life13. Unfortunately, regular blood pressure measurements were unable to be performed due to the limitation of equipment. As ketamine can cause hypertension, it would have been informative to see whether significant changes in blood pressure occurred and to what extent.

Ketamine use is recognised to be safe in the paediatric population although one recent study showed a significant occurrence of hypoxia when used for sedation during flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Ketamine is known to cause emesis, particularly in the paediatric population, and this was demonstrated in our study. Nausea, as an entity, was not aggressively identified in our patients and only vomiting was recorded as an adverse event. In the five patients who had vomiting, 60% were less than five years of age. Of the 22 patients in this age group, 13% had vomiting as a complication, compared with 1.5% in the 127 patients above five years of age. Although higher than reported in other studies for the paediatric population we felt that this was an acceptable rate, particularly when taken into consideration that one patient had a postprandial period of only two hours. It could be suggested that when used in children below five years of age, greater vigilance and lower threshold for intubation could prevent more serious complications.

Hallucinations, emergence phenomena and recovery reactions are often associated with ketamine anaesthesia and may limit its use by physicians. Recovery reactions have been demonstrated to be uncommon in children, with recent studies suggesting that it may also be uncommon in the adolescent and young adult age group. Our series demonstrated that none of the 149 patients, regardless of age group, developed major hallucinations or recovery reactions. This is likely due to the combined use of ketamine and benzodiazepines, which has been shown to decrease hallucinations and recovery reactions. However, we have interpreted this result with care, as our situation was chaotic at best, and mild recovery reactions most likely would have gone unrecognised.

The Kashmir experience highlights the challenges met when medical services are confronted by extremely difficult circumstances. We have demonstrated that a small, dedicated team of healthcare professionals are able to provide treatment with limited resources and still achieve satisfactory outcomes. Of the 149 patients who were administered ketamine, less than 5% developed major complications and no patient developed anaphylaxis, aspiration, hypoxia or cardiovascular compromise. These results are comparable to a those recently found by Paix et al, describing the use of ketamine in the 2004 Tsunami disaster, and by other authors in both wartime and civilian settings. It seems reasonable that the use of ketamine for anaesthesia should be encouraged in disaster settings, such as occurred in rural Pakistan, where medical facilities are under-resourced and the ability to effectively monitor critically injured patients is limited.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Medical and Relief agencies, Australian Aid International and Immediate Assistants, for their support to the Kashmir region during the 2005 earthquake.

Date: 09/06/2018

Source: Medical Corps International Forum 2/2012