Report: A. FRANKE, G. HÖLLDOBLER (GERMANY)

Preclinical Treatment of Casualties in the Field

Clinical demand from the perspective of a field surgeon and a field anaesthetist *

*The content of this article is a personal summary of the contributions presented at a GER Armed Forces Medical Conference - “Damp 2012”

The German Armed forces have been involved in asymmetrical warfare as part of the ISAF deployment for many years now. The majority of the mission-related injuries presented to our treatment facilities in Afghanistan result from gunshot or blast. They include not only perforating and blunt force injuries of the abdomen and thorax, but also extensive soft tissue injuries and serious damage to the joints and the whole axial skeleton. In this scenario, “life and limb saving” pre-clinical casualty care is of utmost importance.

Introduction

In literature, the initial mortality of this injury pattern is about 10%. The majority of those killed in action suffer non-survivable injuries. Approximately 30 %, however, die due to potentially correctable medical problems. . The adequate application of immediate measures in emergency treatment such as haemostasis, securing the airways, thorax decompression in the case of tension pneumothorax as part of emergency competence as well as a standardised, widespread algorithm (such as cPHTLS or cATLS) can reduce initial mortality in these cases. This calls for appropriate training and continuous exercise of all medical service personnel.

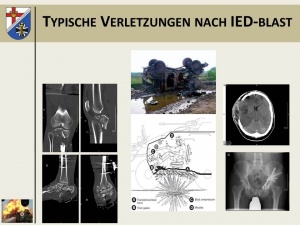

Typical injury pattern after IED blast in a protected vehicle.

Typical injury pattern after IED blast in a protected vehicle.

Furthermore, planning and monitoring subsequent medical treatment and transport logistics play a decisive role. Presenting seriously injured soldiers to a competent field surgeon without delay must be the top priority. In this article we want to discuss where the experienced field doctor is to be positioned in the decision-making process and rescue chains. It also seems necessary to examine whether online patient tracking can improve the quality of treatment not only through the transmission of images of the casualties but also through online monitoring of vital parameters.

Further potential for improvement lies in the training of experienced field surgeons and field anaesthetists. The number of polytraumata treated in an interdisciplinary manner in a specialist clinic at home will also determine treatment tactics and quality concerning patients injured and initially treated in the field. This requires a clear decision that treatment of serious casualties remain the focus of German military hospitals and the recognition of the necessity to maintain, scientifically investigate and make public the competence and expertise established in German military hospitals, so that we can enter into dialogue with civilian professional associations.

Meanwhile, constant improvement of our own skills as well as flexibility of treatment in different operational scenarios are prerequisites for continuous casualty care on a high professional level..

Current threat situation

With the decision of the German Bundestag of 2 December 2001 the Bundeswehr is participating in the ISAF operations in Afghanistan. During this period more than 500 casualties were repatriated to Germany due to their injuries and most of them treated in the Central Hospital of the German Federal Armed Forces Koblenz. The vast majority of the wounded had to be treated here in a specialist surgical department.

It proved possible to identify the main reason for fatalities and the most severe injuries as being road accidents, direct gunshot and shrapnel injuries and damage from explosives, even though as yet there are neither scientifically reliable figures nor is there any scientific investigation of our own fatalities.

Until now all casualties, who were able to be successfully repatriated to Koblenz, survived. For this reason, it makes sense to critically discuss where, from the perspective of a field surgeon and field anaesthetist, there are possibilities for improvement in preclinical treatment in the country of deployment, in order to increase the chances of survival in the event of an injury in the field.

Typical injury patterns in the field

While the injuries following a road accident in the country of deployment are the same to those suffered at home, the injury consequences following a blast injury constitute a special entity. As Fig. 1 shows, the detonation of an explosive under a vehicle results in a massive axial acceleration.

In the past, the passenger compartment and the arrangements of the floor assembly in the operational vehicle were optimised, so that there was a partial redirection or destruction of the kinetic energy. Nonetheless, the occupants are still greatly accelerated. Additionally, as a result of the equipment worn, in the vehicle we carry a load of approx. 20 kg fixed to us, mainly on the shoulder and hip belt. This leads to a direct compression of all structures of the axial skeleton under the axial acceleration and, as the presented cases of the occupants of a vehicle from the field show, causes highly destructive injuries to bones and joints, as well as the most severe craniocerebral injuries.

Together with direct hits by shrapnel, the effect of combustion gases and the pressure wave from the explosion, an injury pattern arises, which is directly life-threatening in its systemic burden for the organism and the consequences. This poses requirements for treatment, which clearly go beyond what we know from the civilian sphere.

As we can currently only sufficiently shield approx. 50% of the body surface from shrapnel and gunshot injuries with the available protective equipment in seated deployment, blast injuries in seated deployment result in extensive soft tissue injuries, which through the combination of widely differing damage mechanisms (combustion, contusion, perforation, dissection, periostomy and degloving) lead to soft tissue injuries to the extremities, which in their extent (size, depth) and systemic burden significantly exceed the effect of comparable damage to the body surface through burn injuries.

Operations-related mortality and time of death

As already stated, these injury patterns are life-threatening, challenging to treat and frequently disabling over time. If this complex is accompanied by perforating injuries to the thorax or abdominal cavity, or there are fractures of the pelvis or large tubular bones or arterial bleeding at the extremities, mortality among soldiers injured on the field of combat rises disproportionately and the time factor until (surgical) haemostasis decides the further outcome.

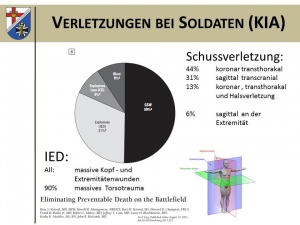

As research findings from the Vietnam War show, which unfortunately remain relevant, the majority of soldiers on the battlefield die within the first hour after injury and, in turn, most of those bleed to death within the first few minutes. More recent analyses, which deal with the injury patterns and causes of death in the framework of wartime deployments of the US army, e.g. in the Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) between 2001 and 2010, show that among those killed in action (KIA), in 31% of cases an IED and in 50% a gunshot wound generally with a coronary shot direction was able to be determined as the leading cause of death.

Of the soldiers killed by a gunshot injury, 44% had a transthoracic, 31% a transcranial and 13% a transthoracic and neck injury. Only 6% had a gunshot injury in the area of the extremities.

It can thus be concluded that only about 6% of the fatal gunshot injuries can be reached by local haemostatic measures, whereas the remainder (approx. 80%) were non-survivable shot injuries or the casualties, at best, could only be saved by means of prompt, rapid transport to an adequately trained and experienced surgeon.

As regards the fatalities through IEDs, all those injured had a serious craniocerebral trauma and in 90% of cases, there was a massive trauma of the trunk. Here too it must be stated that in the majority of cases an injury pattern must have been present that was not survivable under operational conditions.

Starting points for reducing mortality in combat scenarios

If one groups the consequences of current publications and older work, then broadly speaking it can be assumed that approx. 25% of deaths through wounding in the field during operations can be prevented by an optimisation of treatment by first responders and by rapid, considered transport to an adequate treatment facility.

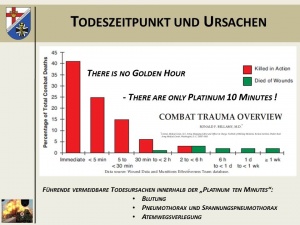

Overview of the time of death after injury suffered on the field of combat and the value of the

“golden hour of shock” and the life-saving immediate measures within the so-called “platinum ten

minutes”.

Overview of the time of death after injury suffered on the field of combat and the value of the

“golden hour of shock” and the life-saving immediate measures within the so-called “platinum ten

minutes”.

As about 90% of combat-related deaths occur before the injured soldier reaches a corresponding treatment facility, all efforts must be directed towards improving first response treatment by lay people or first responders.

Bleeding to death or blood loss through injury to the extremities, the tension pneumothorax and the obstruction of the airways have to be named as the main causes of death.

As it is unrealistic to reserve a physician trained in emergency treatment for each casualty, and the colleague deployed as a BAT within the framework of a combat scenario cannot carry out individual treatment of several casualties, the required measures for therapy of the aforementioned leading causes of death by a sufficient number of trained first responders on site within the framework of “emergency competence” must be taken advantage of, so that the opportunity can be preserved to successfully handle those combat-related avoidable causes of death.

Here it is necessary to establish simple, standardised and, in terms of survival, clearly priority-oriented procedures for simulating scenarios and training for them through drills, so that they can be carried out successfully even under stress and without reflection.

Priority-oriented procedures and training

In the opinion of the authors, if one disregards the optimisation of protective equipment, mortality on the battlefield can be only reduced by means of two mechanisms:

Firstly the prompt elimination of life-threatening complications after the direct injury and secondly the fastest possible and simultaneously careful transport (ideally by helicopter as Fwd AirMedEvac) to an adequate, prepared, informed facility for further emergency medical and surgical stabilisation.

The treatment of the wounded in battle is additionally divided into three phases, with the aim of adopting the correct measure at the most favourable respective point in time on the field of combat:

Care under fire: The phase of treatment under enemy fire has to be limited to rescue from the direct area of combat and to simple, easily applied life-saving measures: e.g. the application of a tourniquet for the staunching of life-threatening external bleeding. “Stop the bleeding”.

Tactical field care: Without enemy contact and protected from direct fire, following a short, as far as possible standardised physical examination of the casualty, priorities-oriented treatment in accordance with the C-ABCDE algorithm can take place.

Tactical evacuation care: Now more advanced medical treatment of the casualty during transport to a treatment facility of a higher level of treatment is possible. In this phase, personnel with higher specialist qualifications in emergency treatment are available for the first time, as are the additional medical supplies of the means of transport.

C-ABCDE algorithm

C - Circulation: Stop the bleeding

As already stated, the leading avoidable cause of death on the field of combat is blood loss as a result of a direct injury from a gunshot or shrapnel. For this reason, under combat conditions “stop the bleeding” has a different value than in the ATLS® oriented towards civilian scenarios. Here we also refer to “c-ATLS”. (c stands for circulation or combat).

The first step in preventing avoidable blood loss is, in principle, the sterile covering of the wound with subsequent local compression, up to the correctly applied pressure bandage. This permits the majority of injuries, including those involving an injury to major veins, to be dealt with.

Alternative securing of airway with larynx tube.

Alternative securing of airway with larynx tube.

If extremities are torn off or there are arterial injuries, the application of a tourniquet is necessary. This has to be applied to the correct anatomical position (proximal upper leg, proximal lower leg, proximal upper arm) with sufficient tension, in order to prevent vascular congestion, which increases rather than decreases blood loss, and achieve sufficient haemostasis.

In the area of the transition from the extremity to the trunk, such as the shoulder or groin, this is not always possible. Here an internal compression of the wound through wound packing should be applied, e.g. with a layered gauze or the application of haemostyptic agents.

These measures are easy to convey and learn in training. Here it must be borne in mind that a soldier writhing in pain and bleeding copiously under combat conditions is a stress factor for the first responder, which frequently leads to a complete failure of the helper. It is necessary to deal with this through the realistic planning of training under combat conditions and with exercises in drill form.

The misapplication of the tourniquet could be counteracted by e.g. integrating the tourniquet into the clothing at the corresponding anatomical position.

A – Airway: Airway management

On the field of combat there is a threat of the airway being obstructed for two reasons. After a serious craniocerebral trauma has been suffered, in unconscious patients the airway often becomes obstructed by the falling back of soft neck tissue (e.g. the base of the tongue). A direct injury to the facial skull by gunshot, shrapnel or the effect of an explosion frequently results in a very extensive, copiously bleeding wound to the face or neck. It can become a major professional challenge even for someone experienced in emergency treatment to secure the airway in the case of such injuries.

The early securing of the airway is of crucial importance for the survival of the casualty. Still in the “tactical field care” phase this must be achieved by means of the simplest possible measures, e.g. through the insertion of a nasopharyngeal Wendl airway tube and moving into a stable side position. In the case of serious craniocerebral injuries and extensive mid-facial trauma, these measures are not always sufficient to ensure a free airway.

Without doubt, in these cases in the homeland endotracheal intubation would be called on as the emergency treatment “gold standard” for securing the airway. Under the depicted military conditions, however, alternative means for securing the airway such as supraglottic aids (larynx tube, larynx mask) gain in importance. Their application can be learned with relatively little training effort.

Thus it is in most cases possible to avoid surgical cricothyrotomy, which is unfortunately associated with a high complication rate. In the view of the authors, this should be regarded as the “ultima ratio” of securing the airway and is technically by far more challenging on patients than often presented in training scenarios.

All methods for securing the airway have one thing in common: they must first be practised under conditions that are as realistic as possible. Only thus can an acceptable certainty of action for the user be obtained.

B – Breathing:

A penetrating thorax trauma will, as the primary consequence of injury, very often result in a pneumothorax or haematopneumothorax. The typical clinical signs of a developing, life-threatening tension pneumothorax are generally unable to be diagnosed on the field of combat.

In external conditions that can be assumed to be extremely difficult, it is not always possible to identify with certainty symptoms such as hyperresonant percussion sound, emphysema of the skin, upper venous congestion, tracheal shift or decreased breathing sounds on one side.

The suspected diagnosis of a tension pneumothorax must therefore be assumed for every penetrating wounding of the trunk with subsequently developing massive shortness of breath.

The surely desirable immediate creation of thorax drainage (the “gold standard” in the home country) is unrealistic for the “tactical field care” phase. Here the life-saving relief puncture of the tension situation will generally have to be carried out by medical laypeople (first responders-B, CFR), combat paramedics or paramedics.

This invasive measure has to be practised in advance in drill form on a model, or even better on a corpse. The treatment of open thoracic wall injuries with special airtight adhesive films can also be trained.

All patients with a penetrating torso injury have to be closely monitored on the transport for an acutely occurring “B-problem”. An extremely suitable technical option for this is the continuous derivation of the pulse oxymetry.

C – Circulation: Volume therapy

In the early phase of treatment, the control of life-threatening bleeding (“stop the bleeding”) takes priority over volume replacement with crystalline or colloidal infusion solutions. The problem of the access path for the infusion and pain therapy can be regarded as solved. If the placement of intravenous cannulas fails, a safe access path can be established quickly through the use of intraosseous needles.

The concept of so-called “permissive hypotension” should be practised in the event of uncontrolled bleeding. To prevent increased bleeding through higher blood pressure and thinning of the coagulation factors, volume replacement is only carried out with restraint.

An exception to this are patients with craniocerebral trauma. For this patient clientèle, normal blood pressure is always the objective. Haemodynamically stable patients are provided with a venous access, but here, however, the forced volume supply is foregone.

D – Drugs: Analgesia

Beginning very early on with an effective pain therapy in the field is of very decisive importance for the fighting troops, and is also psychologically important. This should be commenced even before the “tactical evacuation care” phase. Opioid analgesics (morphine auto-injectors, alternatively oral transmucosal Fentanyl) or the sedation-analgesia (Ketamine in combination with benzodiazepines) are available as appropriate pharmaceuticals for this. However, these potent analgetics have to be administered in a sufficient dosage and dangerous overdoses especially through mixed applications prevented. The soldiers administering these drugs have to learn how to identify early on and treat undesired side effects, such as hypoventilation after the administration of opioids.

E–Environment: Hypothermia prophylaxis

After a wounding, the potentially fatal trio of hypothermia, coagulopathy and acidosis must be prevented. Increased post-traumatic mortality is frequently described for this constellation. The problem of hypothermia in the operational scenario is more relevant than for the treatment of the seriously injured in the home country, since when deployed abroad we generally have to assume significantly longer transport times. The consistent adoption of simple measures for keeping the patient warm is all the more important. The removal at an early stage of soaked clothing and active external rewarming play a decisive role. Additional insulating rescue blankets should also be employed generously.

Training content

Blast injury of mid-face.

Blast injury of mid-face.

The aim of all training efforts is to obtain certainty of action for operations abroad. Compliance with previously repeatedly trained, and as simple as possible, treatment paths and the learning of priorities-oriented action (“treat first, what kills first”) is a method for attaining this required resistance to stress in the combat situation.

The elementary basic prerequisite is confidence in one’s own confidently acquired manual skills. At all treatment levels and for all levels of qualification (EH-B [first responder], CFR, emergency paramedic, medical corps sergeant (paramedic), medical officer (physician) rescue medicine), this professional ability must be reinforced through repeated skill training in drill form (stop the bleeding, save the airway, thorax relief puncture, the creation of intravenous or, alternatively, intraosseous access paths etc.). When conveying the training content in greater depth, the most realistic simulation possible of external stress factors plays an important role.

Training in accordance with recognised course concepts such as TCCC®, PHTLS®, ATLS®, and ETC® offers the unique opportunity not only to establish excellent training of basic manual skills, but also an internationally standardised procedure for the treatment of severely injured soldiers.

A “common language” of the treatment team with clearly defined concepts and principles of action is indispensable for successful trauma treatment in the field. This requirement is particularly necessary for cooperation in multinational teams, as we frequently find in the pre-clinic and clinic, especially in the field hospital.

Assessing the situation, information management, outlook

These comments make it clear that, in the view of the authors, two basic pillars are essential for reducing mortality on the field of combat. Live-saving immediate measures carried out by first responders trained in drill form and rapid, careful transport to a pre-informed adequate medical facility.

The obtaining of information and assessment of the situation play a major role in this. The management of the casualty is made easier on site by own clinical experience and detailed knowledge of the possibilities and abilities of the medical facility.

The question remains of whether technical possibilities can be developed and established for the future which ‒ similarly to an online system, which maps the position, direction of action and firing power of an individual soldier ‒ transmits vital parameters, image of the pupil status and the injuries and position of a casualty.

Data collection by a first responder on the spot and, correspondingly, transport planning by RCC or PECC would be conceivable. With regard to the current situation with ISAF, constellations of injury patterns and the number of wounded are thinkable, which make necessary an initial differentiated distribution between e.g. Role 2 and Role 3. Especially in this situation, realistic (neither over-triage nor under-triage) categorisation is the fundamental prerequisite for the further management of treatment.

Currently, differently equipped air-support rescue resources (platform: PEDRO or MERT) are also available in the field. These each have their own properties, benefits and use different resources. The deployment progresses in line with the assessment of the situation locally and has until now depended on the information communicated by the local leader. This content and the specialist medical knowledge concerning these aspects of the situation assessment also have to be conveyed realistically to the military leaders.

If the casualty then reaches the medical facility providing further treatment, he profits from the presence of a surgeon and anaesthetist with field experience. At this point it is important to point out that this surgical and anaesthesiological expertise has to be maintained.

Overview of the causes of death of soldiers (KIA = killed in action) of the 75th Ranger Regiments of

the US army in warfare between 2001 and 2010 (n=32).

Overview of the causes of death of soldiers (KIA = killed in action) of the 75th Ranger Regiments of

the US army in warfare between 2001 and 2010 (n=32).

This can most easily be acquired within the framework of an activity in the homeland in a facility providing maximum treatment with a sufficient number of treated polytraumata. Regular participation in corresponding realistic practical courses, which also include e.g. animal models (DSTC), should be required and provided for.

From the clinical field medicine perspective, the efforts of the managers of the medical service surrounding these prerequisites must be supported with conviction and repeatedly called for from and presented to political decision-makers.

This of course also includes the establishment of a potent medical deployment and trauma register, which from a clinical viewpoint too makes it possible for quality control of the treatment to be carried out starting from the first 10 minutes after an injury suffered in the field.

As the individual nations at the NATO level only have very low numbers of casualties, but possess medical expertise and specialist knowledge in specific fields, it is necessary to make this data available among them and make reliable statements regarding that data.

Only this exchange of data and findings, the mutual optimisation of structures through international dialogue and a focus on resources, where that is medically meaningful, make it possible to meet the challenges which may arise for operational planning in the short term from the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan and the planned withdrawal of troops.

Summary

In summer 2011, the S 3 guideline on the treatment of the seriously injured was published by the responsible medical associations. This publication also makes available to the medical service of the Bundeswehr in the field a guideline for the treatment of the wounded in the pre-clinic, shock room and first op phase.

Doubtlessly, in terms of the conditions and injury patterns, the treatment of wounded soldiers differs from that in the civilian sphere.

Military threat, working in multinational teams, in some cases long transport times and the predominance of blast and penetrating injuries may be mentioned as special factors here.

Fatal bleeding is the primary avoidable cause of death on the field of combat. It is therefore essential to stop the causes of bleeding as quickly as possible.

The further preclinical treatment of the seriously injured should be carried out according to priorities and comply with clearly defined treatment paths. An algorithm-oriented procedure, as prescribed by such concepts as PHTLS®, ATLS® and ETC®, can be helpful here.

Preclinical treatment in the field has to focus on the acute threat to the life of the wounded soldier and primarily solve bleeding problems (C problem), then secure breathing (A and B problem), and ensure sufficient analgesia (D problem) as well as the maintenance of body warmth at an early stage (E problem).

Then it must prove possible to successfully identify the injured soldier, who is not stable following initial treatment by first responders (“life-saving skills” in the “first 10 platinum minutes”) and must therefore be transported as quickly as possible by Fwd AirMedEvac (helicopter) to the most suitable medical treatment facility (ROLE 2 or ROLE 3). The time factor plays a decisive role with these wounded soldiers.

Only if the patient is stable and his life not under threat can there, from the clinical perspective, be discussion of deviating from the specified target of the “golden hour of shock” and leaving the hour radius for transport to the most appropriate medical facility,

It is only through the consistent training of priorities-oriented procedures that we will succeed in achieving certainty of action in the treatment of the wounded in combat. Therefore the treatment of field-specific injury patterns with the consistent use of training resources supported by simulations should be practised within the team in the conditions that are as realistic as possible.

Further literature with the authors.

References: [email protected]

Address for the authors:

Private Lecturer Dr. Axel Franke, MD Lieutenant Colonel MC

Department of Accident Surgery and Orthopaedics, Reconstructive, Hand and Plastic Surgery

Hospital of the German Federal Armed Forces Hamburg

Rübenacher Straße 170

56072 Koblenz

Date: 09/18/2018

Source: Medical Corps international Forum 4/2012