Report: H. Frickmann1, D. Sturm2, E.-J. Finke (GERMANY)

Risks of Infection as a Result of Foreign Tissue Implantation Injuries and Sexual Violence in Asymmetric Conflicts

As experience from the most recent crisis regions in the Middle East (Gaza, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria), in Central Africa (including the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mali) or in Afghanistan very clearly prove, asymmetric warfare will determine the nature of military conflicts in future. The Medical Service must be prepared for this development too. In such warfare, military units are faced with irregular forces that usually operate in a concealed manner. These irregular forces compensate for their military inferiority with regards to strength, logistics and equipment partly by resorting to evil and outlawed combat methods, thus deliberately violating international rules and standards such as the Geneva Conventions or UN agreements and resolutions. As a result, the Medical Service can be confronted with highly severe forms of physical and mental trauma.

Introduction

This overview looks at a risk associated with asymmetric warfare that is often neglected, the reason being that it is not particularly obvious: the risk of a violence-related infection with pathogens of sexually and parenterally transmitted diseases such as syphilis, gonorrhoea, hepatitis B, hepatitis C or AIDS. Theoretically, other microorganisms on the skin and mucous membranes of the attacker (e.g. staphylococci, streptococci, pathogenic intestinal bacteria, herpes viruses, etc.) can also play a role.

The pathogens are usually transmitted unknowingly. However, it could also be the intention of attackers with a contagious disease to secretly infect a target population. Merely the threat of a serious and frequently incurable infectious disease would suffice to psychologically terrorise potentially infected individuals, causing insecurity, fear and even post-traumatic stress disorders that call for targeted medical treatment.

The mechanism of virus transmission in suicide bomb attacks

Risk of virus infection transmission through

suicide bombers. Photo credit: Graphic illustration

by Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on a photograph with

the cooperation of comrades from the

Bundeswehr Medical Service who wish to remain

anonymous.

Risk of virus infection transmission through

suicide bombers. Photo credit: Graphic illustration

by Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on a photograph with

the cooperation of comrades from the

Bundeswehr Medical Service who wish to remain

anonymous.

One of the most effective and most commonly used weapons in asymmetric warfare and terror attacks are improvised explosive devices (IED). These devices are either attached to the suicide bombers' body or are hidden in public places and on frequently used roads. Detonated either directly by the attacker himself or by means of a telephone, the contents of the explosive device are distributed centrifugally with high kinetic energy. In most cases, this results in the bodies of the suicide bomber and of victims who happen to be in the direct vicinity being severely injured and fragmented by penetrating injuries. When this happens, foreign tissue such as bone fragments and bits of muscle can enter the wounds of victims.

If the suicide bomber is infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is contagious, infectious tissue fragments from the bomber can penetrate the victims' bodies when the IED is detonated. In addition to direct injuries, this can also cause serious diseases.

The Bundeswehr Medical Service has often observed cases of foreign tissue implantation as a result of suicide attacks during missions in Afghanistan (information provided by Anja Schlegel, MD, Lieutenant Colonel (MC)). Academic literature only contains descriptions of isolated cases of virus transmission as a result of foreign tissue becoming embedded after suicide attacks. The theoretical possibility of such transmissions, however, has been discussed many times.

Transmission of blood-borne viruses through sexual violence

Although sexual violence in connection with military conflicts can be treated as a war crime (UN resolution 1820 (S/RES/1820 (2008))), a past study has extensively revealed that cases of rape during wartime are common. Mass rape can be regarded as a form of asymmetric warfare, particularly in ethnically motivated conflicts. In such cases, not only males but also the female population in question are harmed both physically and mentally, stigmatised and often excluded from the community, thus diminishing the latter's reproductive capacity.

Recently, due to knowledge about transmissibility and the medical after-effects of transmission, rape has also come to be a deliberate act aimed at infecting the enemy (women and men) with life-threatening diseases. In particular if such assaults remain unreported or are not reported soon enough, which is regrettably often the case because the victim is too ashamed, there is a risk of infection with various sexually transmitted diseases. Of these, HBV, HCV and HIV entail the most severe consequences.

HBV and HIV are mainly transmitted sexually. However, the risk of infection with HCV through injuries, as those that can occur as a result of sexual violence, is also on the increase.

This study therefore focuses on the potential dangers of contracting HBV, HCV or HIV as a result of foreign tissue becoming embedded as a result of suicide bomb attacks or sexual violence. It aims at analysing, amongst other things, whether and to what extent an infection with the above-mentioned viruses has thus far been a deliberate act during asymmetric conflicts or terror attacks. The objective was to analyse current knowledge on violence-related virus transmissions and to define medical countermeasures for the Medical Service.

Methods

Using the "PubMed" database (www.pubmed.com), a selective literature research on the subject of "violence-related transmission of blood-borne viruses" was carried out over the last three decades (1983-2013). In addition, prevalence data on hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV infections from the MEDINTEL (medical intelligence) structure, Subdivision VI (Preventive Medicine, Preventive Health Care, Health Promotion), Division A of the Medical Service Command in Koblenz were evaluated for current Bundeswehr operational areas. In order to establish the military context, the following were used as search terms: HBV, HCV, HIV, and sexually transmitted diseases in varying combination with transmission, intentional transmission, foreign tissue implantation, infection, suicide bombing, rape, assault, blast injury, risk, war, terror and genocide. Studies not referring to transmissions in a military, terrorist or criminal context were not included in the analysis.

Results and discussion

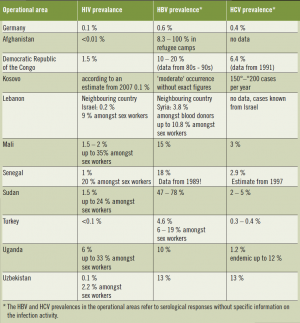

Comparison of the prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections in Germany and in current

Bundeswehr theatres of operation, April 2013. Source: Bundeswehr-internal "MEDINTEL" reports

Comparison of the prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections in Germany and in current

Bundeswehr theatres of operation, April 2013. Source: Bundeswehr-internal "MEDINTEL" reports

A total of six articles dealing with the infectiological results of foreign body implantation in the event of suicide bomb attacks and 12 publications on pathogen transmission through rape in military or ethnic conflicts were analyzed. Of the latter, eight formed part of one extensive meta-analysis. The most important studies are quoted below. The affected target groups of the bomb attacks were mainly Israeli and British civilians. Infectiological consequences of cases of mass rape, some of which occurred across the whole country, were primarily reported from the following Central African countries: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Southern Sudan, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Burundi. In total there were two case descriptions of moleculobiologically confirmed incorporation of foreign tissue containing HBV following suicide bomb attacks, but the infection was prevented from developing by means of a post-exposure vaccination. The African studies primarily described the infectiological effects of sexual violence at a population level.

Risks of infection following suicide bomb attacks

While there is no reliable data available on the efficiency of virus transmissions as a result of suicide bomb attacks, it does seem generally plausible that an infection is a possibility. The high temperatures that prevail during the fragmentation of the body of a contagious suicide bomber when the bomb is detonated could be a critical factor in this context and could inactivate large proportions of initially viable viruses. This type of inactivation, however, must be considered unreliable because the heat takes little time to take effect and the surrounding tissue (e.g. bones, muscle tissue, blood) can provide a certain amount of protection against the heat. No studies have been conducted to this effect, however. If the initial virus count is high enough, as is typically the case, for example, in the viremic phase of acute HBV, HCV or HIV infections, a sufficiently high infectious dose could remain and result in infection. This applies in particular to large tissue components such as bone or cartilage fragments, which are exposed to less heat per unit of volume.

Israel was confronted with this problem during the Intifada (2000 – 2002). Medical forensic tests carried out on 456 victims of suicide bomb attacks and 162 killed terrorists revealed for the first time that there is a risk of the injured becoming infected by penetrating tissue components from an infected suicide bomber or contaminated splinters of metal and glass. Braverman et al. [9] 2002, for example, described the case of a 31-year-old woman where a bone fragment became embedded in her throat. HBV-DNA was detected via PCR in the post-mortal blood of the suicide bomber. Subsequently, active and passive hepatitis B post-exposure prophylaxis measures were initiated in order to prevent the infection from developing. As a result of this incident, the Israeli health ministry ordered for all injured individuals to be actively vaccinated against hepatitis B and for routine forensic laboratory tests to be carried out on the tissue of suicide bombers following comparable suicide bomb attacks with the aim of detecting HBV, HCV and HIV infections.

In 2005, when looking at the cases of a total of 94 patients in whom foreign tissue had become embedded after suicide bomb attacks, Eshkol & Katz only came across one case of HBV virus transmission. In this case, an immediate vaccination prevented the infection from developing. Following exposure, all those concerned had received broad-spectrum antibiotics, tetanus antitoxin and a hepatitis B vaccination.

Whether virus transmission was intentional as part of the attack or a coincidence because the perpetrator was infected remains unanswered. There is also uncertainty about the existence of unreported cases of infected injured individuals in whom no appropriate infection diagnosis was carried out immediately after the attack or later.

On the whole, however, it seems that cases of virus transmission in association with suicide bomb attacks are rare because otherwise they would have presumably received greater response in the media. It is precisely for this reason, however, that intentional virus transmission could succeed since, after an attack, first responders are likely to only focus on treating the wound and to disregard transmission of the aforementioned viruses. In addition, post-exposure prophylaxis or treatment must be given very soon after exposure.

At present, specialists from the US armed forces with ISAF are also collecting and analysing biological samples from suicide bombers (information provided personally by Florian Helm, Commander (MC), senior medical officer for preventive medicine for Afghanistan), something which the Bundeswehr has not started doing regularly.

Risks of infection as a result of sexual violence

As already mentioned, the risk of infection is high for the victims of sexual violence in areas of conflict.

While there is still no evidence of deliberate infections through suicide bombers, there is adequate proof of intentional HIV transmission in cases of conflict-related mass rape for the purpose of genocide, e.g. from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. During the conflicts that took place between 1996 and 1998 alone, more than 50,000 sexual attacks were carried out by combatants in the eastern regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. An estimated 60% of these combatants were infected with HIV.

More than just humiliation – risks of infection in warassociated

cases of rape. Photo credit: Graphic illustration by

Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on a photograph with the cooperation of

comrades from the Bundeswehr Medical Service who wish to

remain anonymous.

More than just humiliation – risks of infection in warassociated

cases of rape. Photo credit: Graphic illustration by

Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on a photograph with the cooperation of

comrades from the Bundeswehr Medical Service who wish to

remain anonymous.

In a large-scalemeta-analysis carried out in 2007, using HIV prevalence as an example, Spiegel et al. evaluated the general influence of conflict-related sexual violence on the spread of blood-borne viruses. 65 publications from 7 conflict regions (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Southern Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Burundi) were systematically assessed. Despite extensive use of sexual violence in these conflict regions, there was no proof at the population level of a significant increase in HIV prevalence in the ethnic groups concerned.

While the data from Spiegel et al. suggest that the spreading of blood-borne viruses through sexual violence with terrorist intent is rather ineffective, analyses at the population level do not help victims to assess their individual risk. Since post-exposure measures only have minor side effects in comparison with the consequences of an infection, such measures should be applied generously.

Prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections in Bundeswehr theatres of operation

Data on the prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV in Bundeswehr theatres of operation is sketchy because the regional health services sometimes do not investigate or even report due to a lack of data or for religious or political reasons. The region-specific risk situation is assessed for the Bundeswehr on the basis of open information sources through the MEDINTEL structure. In many cases there are only estimations or data from neighbouring countries.

The prevalences for these virus infections are sometimes considerably higher in theatres of operation than they are in the home country. As a result, the risks of infection for those exposed in a suicide bomb attack or as a result of sexual violence varies from operational area to operational area. The extent to which insurgents or terrorist groups deliberately select contagious individuals for suicide bomb attacks remains uncertain. However, due to limited capacities for proving infectivity and uncertainty as regards the development of an infection, it is rather unlikely that they do so. On the other hand, the threat potential of a possible infection must not be neglected.

Secondary psychological effects

The main focus of medical care given to victims of suicide bomb attacks is usually to save and provide treatment to the injured. If a victim has also been infected with HIV, HBV or HCV as a result of the implantation of infectious foreign tissue, clinically severe or fatal diseases could develop after relatively long incubation periods. Treatment of these diseases would be very difficult and lengthy. This could result in delayed secondary psychological after-effects, incapacity to work or even invalidity.

Aware that they have been injured by flying infectious foreign tissue (bone fragments) or contaminated parts of the explosive charge, victims have to live with the fear that they have been infected until the contrary has been proven. For appropriately informed soldiers, this can intensify already existing post-traumatic conditions. There are also the consequences of the risk of infecting a partner, which can cause even greater psychological pressure.

That merely the fear of intentional infections with life-threatening diseases such as AIDS can lead to chronic psychiatric disorders has been clearly proven by victims of robbery, break-ins and hostage-taking. These victims were threatened with a needle rather than with a traditional weapon. Due to the fact that there are only a few recorded individual cases of HIV transmitted through needle attacks, this enormous psychological effect is underestimated.

Diagnostic challenges

In the case of suicide bombers, who usually do not survive the bomb explosion, the task of finding suitable sample material from their mortal remains, which are in most cases scattered over a wide area, is very challenging. To carry out on-site rapid tests to detect blood-borne viruses, blood samples are needed that are difficult to take from disseminated body parts and after haemostasis has begun.

In addition to the fact that the medical personnel has to take courageous action and is likely to have to overcome a state of shock or revulsion, it is also necessary to have available long and large cannulas. This is the only way to puncture deep large blood vessels and the heart in order to extract residual blood from the largely bled body of the suicide bomber.

An initial diagnosis at the scene is only possible on the basis of solid, simple rapid test systems. While serological laboratory HBV, HCV and HIV tests carried out on blood from a dead body using large automatic equipment works reliably and – with haemolysis-related restrictions – the PCR also delivers reliable results, rapid test systems are not usually validated and accredited for this purpose. To confirm the results, phylogenetic bioforensics by means of PCR and downstream sequence analysis are possible. For the HIV rapid tests used in the Bundeswehr, valid results from blood samples taken from dead bodies were recently demonstrated up to 48 hours after death. According to American tests, reliable results of rapid HIV tests can also be obtained from samples that have been contaminated by the environment. The quality of rapid hepatitis tests, on the other hand, is quite heterogeneous, in particular under unfavourable pre-analytic conditions.

As illustrated by our Israeli colleagues, another possible test approach is to examine embedded tissue fragments using molecular methods. Such procedures, however, are usually unavailable for guaranteeing a fast diagnosis and an initial risk analysis in the mission country.

In order to obtain forensic proof of or in order to rule out violence-related infection in asymmetric conflicts or following terrorist attacks, phylogenetic, sequence-based methods are required. This has been proven by successful studies on criminally motivated, intentional HIV transmission of infected blood. However, such bioforensic tests are dependent on specially qualified laboratories. What is more, phylogenetic analyses only make it possible to reliably rule out a transmission but do not provide conclusive proof of a transmission. The latter therefore always requires the element of situative plausibility as well.

Generally, all the methods used for this purpose have to be evaluated, validated and, if necessary, accredited beforehand with the medical study material in question in order to meet valid quality requirements and, as a result, to be recognised for forensic proof.

Post-exposure prophylaxis and treatment

As a consequence of the observed cases, the Israeli health ministry ordered, in the event of suicide bomb attacks, for all those injured to be actively vaccinated against hepatitis B and for routine forensic laboratory tests to be carried out on the tissue of suicide bombers in order to identify HBV, HCV and HIV infections. In addition, those affected were given post-exposure treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and tetanus antitoxin.

There is currently no post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) available against HCV. However, it still makes sense to screen the index person for HCV in order to estimate the infection risk of the attack victim. Acute studies of the HCV infection have an excellent prognosis under interferon-alpha treatment, which means that it is important to identify early infection stages. In accordance with the long incubation period, attack victims of HCV-infected suicide bombers should be screened regularly over several months for an HCV infection.

Following a deliberate attempt to infect others with HIV, the PEP measure should be applied as soon as possible, e.g. in Role 1 or Role 2 facilities, preferably within 2-4 hours following exposure. This is because after HIV has come into contact with its target cell, it only takes between 30 minutes and a few hours for it to become internalised in the cell. The severe consequences of an HIV infection in comparison to the assessable side effects of antiretroviral medication is reason enough to apply such medication generously. In this context, there is the option of discontinuing the prophylaxis as soon as the suicide bomber has reliably tested negative for HIV. For this purpose, mobile aid stations, mobile surgical hospitals and field hospitals should, insofar as possible, be equipped with HIV rapid tests for performing preliminary tests on blood from the dead body of the suicide bomber and with antiretroviral PEP medication for injured victims.

In the event of potential transmission, pending HIV tests should never cause a delay in applying PEP but should only help to decide whether or not to discontinue the PEP. The decision whether or not to discontinue the PEP is to be made by the responsible physician, taking into account all the relevant aspects concerning the likelihood of an intentional or accidental HIV transmission.

Combined use of tenovovir/emtricitabine was recently authorised as an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) but has only been evaluated for sexual HIV transmission. It remains unclear whether PrEP effects can be overcome by a high viral load in the event of embedded foreign tissue. At least for low-risk scenarios such as those in Afghanistan, it seems unnecessary to provide prophylactic PrEP as long as the PEP is always available in the task force's medical facilities.

Aspects of medical biological defense

Courageous action after overcoming the moment

of terror – conditions for taking blood samples from the

tissue of a dead suicide bomber are difficult. Photo

credit: Graphic illustration by Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on

a non-classified photograph courtesy of Anja Schlegel,

MD, Lieutenant Colonel (MC), ISAF 2006.

Courageous action after overcoming the moment

of terror – conditions for taking blood samples from the

tissue of a dead suicide bomber are difficult. Photo

credit: Graphic illustration by Dr. Daniel Sturm, based on

a non-classified photograph courtesy of Anja Schlegel,

MD, Lieutenant Colonel (MC), ISAF 2006.

As such, the accidental transmission of infectious diseases via the infected tissue of a suicide bomber or through sexual violence is primarily a medical or forensic problem. The threat and use of deliberate infection as part of asymmetric conflicts through suicide bombers who are aware that they have an infectious disease would have to be regarded as a special form of bioterrorism. This would be the case, for example, if suicide bomb attacks are aimed at spreading large amounts of pathogens e.g. with infected conserved blood or fluid cultures of pathogenic microorganisms. Table 1 shows that high prevalence in certain regions means that persons carrying the HIV or HBV infection – particularly in social fringe groups – could be used as sources of pathogens for taking blood samples. However, the efficiency of a transmission mechanism in connection with the explosion of IEDs, which – as experience so far has shown – only affects those who are directly injured as a result of being very close to the bomber at the time of the explosion, is difficult to calculate. It is uncertain to what extent an infection could be triggered not only through penetrating infectious foreign tissue components or contaminated splinters but also as a result of breathing in aerosols of infected tissues.

From the perspective of medical biological defence, the possibility of a deliberate infection through suicide bomb attacks as a form of asymmetric warfare is an interesting subject. It cannot be ruled out that an enemy is not particularly interested in direct military success. Merely the threat of spreading dangerous infectious diseases can mentally traumatise a target population for a long time.

The specified aspects should be taken into account both in risk analysis prior to operations in crisis regions and in medical biological reconnaissance and biological verification of unusual outbreaks of illnesses.

Conclusions

Current knowledge shows that for armed forces, the risk of certain pathogenic agents being transmitted in the event of suicide bomb attacks or sexual violence is relatively low.

Although terror attacks aimed at transmitting parenterally and sexually transmittable hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HI viruses or other biological agents have so far remained unproven, such attacks are theoretically possible.

The Medical Service should take these risks into account in medical care and in medical B defence of the armed forces.

In the event of suspected potential infection risk on operations, the following medical measures are recommended:

- immediate tissue and blood samples (serum and EDTA plasma) are to be taken from the living or dead suicide bomber by forensically trained medical personnel,

- embedded foreign tissue parts are to be removed from the injured for medical and forensic tests and blood samples (serum) are to be taken for serodiagnosis,

- initial screening is to be carried out on blood-borne viruses by means of rapid tests in role 1 and 2 medical facilities,

- samples are to be sent to special laboratories in the home country in compliance with the chain of custody and chain of evidence,

- specialised medical and bioforensic laboratory tests are to be carried out to confirm or rule out that the suicide bomber is infected,

- the injured are to be tested for HBV, HCV and HIV infection,

- immediate hepatitis B immunoprophylaxis (if necessary active-passive combination vaccination) is to be given if the immune status of the victim is unknown or severe infection is suspected,

- HIV prophylaxis is to be introduced as soon as possible if an infection is suspected,

- the victims are to receive medical observation and to undergo regular serological screening in order – due to the prolonged incubation periods – to record the development of an infection,

- victims and their relatives are to be briefed and instructed (cave! men having sex with men!, potentially pregnant women!),

- victims and their relatives (PTBS, suicide risk!) are to receive psychotherapeutic advice.

These measures call for specialist instruction and medical planning of material, personnel and infrastructural requirements. Amongst other things, this entails the provision of suitable examination capacities and diagnostics in the operational area and in the home country, forensic training for medical personnel, and binding recommendations for the prophylaxis and treatment of persons who are suspected of being infected or are sick.

In addition, efforts should be made towards entering into a national and international specialised dialogue on the aspects of violence-associated infections, the aim being to exchange the latest knowledge and experience in this area.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in terms of the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Disclaimer

The contents above do not represent the views of the Federal Ministry of Defence (FMoD) but reflect the opinions of the authors.

*Acknowledgment

This article was first published in German in ‘Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift’. Translation and reprint with kind permission of the publisher.

References: [email protected]

Author

Dr. med. Hagen Frickmann, Major MC

Dr. med. Ernst-Jürgen Finke, Colonel (ret) MC

Date: 03/28/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (3/2013)