Report: L. WOLFF (US)

Orthopedics in the Austere Environment –Thinking “Outside the Box”

The following case report reflects the unique challenges faced by the Orthopedic Surgeon working in a forward surgical

setting, in an austere environment, with limited available resources. Providing definitive care for difficult cases involving

the local population is common due to the limited availability of local medical infrastructure.

United States Army Forward Surgical teams (FSTs) have historically been small mobile units able to provide medical support for a traditional advancing front line in a theatre of battle. These units typically are comprised of one anesthetist, two surgeons, multiple medics, Operating Technicians, ICU nurses and administrative staff. Capability of these units is limited, and damage control surgery for the acutely injured is typically performed within the golden hour after injury. Resuscitation, hemorrhage and contamination control, stabilization of fractures and temporary treatment of abdominal and thoracic injuries are the primary objectives before evacuation to a higher echelon of care. With current conflicts involving nonlinear movement of troops and the disappearance of the historic “front line,” FSTs have become more stationary but still within close proximity to areas of ongoing operations.

Medical rules of engagement for the FSTs in Afghanistan comprise the protocols for treatment for ISAF soldiers, Afghan military and civilian casualties. These Med ROEs are fluid and may change depending on the capability of the FST, tempo of ongoing operations and the availability of higher echelons of care, particularly for civilians. Injuries that threaten life, limb or eyesight are given a priority for these patients, and if successfully treated, may significantly affect relations with the local population.

From the Orthopedic standpoint, treatment of these patients poses unique challenges and the opportunities to significantly improve their the quality of life and function. These challenges include: the often chronic nature of the injury, previous sub-optimal treatment, local infection, inadequate nutrition, language and cultural barriers, poor host biology and limited equipment available in the FST setting. Treatment of such local patients frequently requires the Surgeon to think “outside the box” of normal paradigms that he or she would follow in their private practice, and modify these as needed in such an austere environment. Such is the case for the following patient.

In April of 2008 the United States Army 2nd FST was stationed for 15 months at Orgun-E in eastern Afghanistan providing care to ISAF soldiers, ANA, ANP and local civilians from the near-by town of Orgun. A tribal elder presented to the weekly clinic complaining of pain and deformity of the left forearm. Through an interpreter he stated that he was injured by an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) approximately one year prior to presentation suffering an open fracture of the proximal radius and ulna. This was treated with open reduction and internal fixation with two plates and multiple screws at a local hospital. Unfortunately, he developed a chronic infection, loss of fixation and a residual deformity that left the arm functionless. His neurovascular status in the hand was intact, but did have chronic edema. The incision over the forearm showed a chronic draining sinus and exposed hardware.

He was taken to the operating theatre for a planned two stage treatment consisting removal of the infected hardware, debridement of the infected nonviable bone and soft tissue, and wound closure over a drain with splint application. He was given a month of broad-spectrum oral antibiotics. Culture sensitivity and IV antibiotics were not available. Consideration as to what form of definitive stabilization would be used included external fixation or internal fixation using external fixator equipment, as that was all that was available.

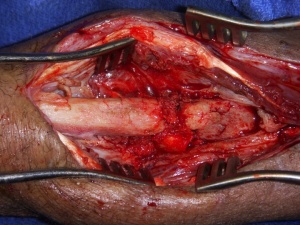

After one month, the patient returned to the FST with no signs or symptoms of infection and a healed wound. He returned to the operating theatre where the radial and ulnar nonunions were addressed. After exposure through separate incisions, the nonunion sites were debrided back to bleeding viable bone with excision of the intervening fibrous tissue. The radial fracture was then stabilized first with an interosseus Hoffman II External Fixator 5mm half pin first placed distally in the radial canal. After opening the proximal canal, the fracture was reduced and the pin manipulated proximally to achieve fixation near the radial head. Next, a separate 5mm half pin was placed through the olecranon and advanced through the ulnar canal across the ulnar fracture site. These pins were placed using the hand drill with limited fluoroscopy.

Bony defects in the radius and ulna were filled with autologous iliac crest bone graft. Post-operatively, the fixation provided good stability at the fracture sight and correction of the deformity. The incisions were closed primarily and no drain was used. The patient was discharged home with oral antibiotics.

Routine follow was performed at two, six and twelve weeks after surgery. There was no recurrence of the infection, and the patient continued to show progression of healing across the fracture sites on serial radiographs. Although not completely united at last follow-up, the patient had excellent function of the arm and hand for activities of daily living and denied any pain.

This case report reflects the unique challenges faced by the Orthopedic Surgeon working in Forward Surgical setting, in an austere environment, with limited available resources. Providing definitive care for difficult cases involving the local population is common due to the limited availability of local medical infrastructure, frequently making the FST the end of the line for treatment. The patient was counseled that this was a salvage procedure to restore function of the limb and had never been attempted by the author using external fixation pins as intramedullary fixation devices. Attempting such surgeries and thinking “out of the box” requires informed consent of the patient, input from available colleagues and imagination on the part of the Surgeon. Being flexible as the case develops and having a back up plan are a must. Such cases can bring great fulfillment if the patient does well, and experience of what not to do if they don’t.

Author:

LTC Luther H Wolff MD

United States Army Reserve orthopedic surgeon since 2001

Medical School Mercer University School of Medicine

Date: 04/08/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (1/2014)