Article: Nina Sinthofen, Hans U. Schmelz

Fournier Gangrene – Yesterday and Today

Fournier's disease is defined as a particular form of infectious, necrotising fasciitis affecting the perineal, perianal and scrotal regions. This article looks at historical as well as actual facts and describes one prominent case of fournier’s disease.

The French professor of dermatology and venerology, Jean Alfred Fournier (1832 - 1914) is generally regarded as the man who gave his name to Fournier's disease. His research and areas of interest, however, focused more on the then extensive field of syphilitic diseases. However other researchers had also looked at this topic long before Fournier and written about their theories: in 1764, Baurienne described a similar picture, and much earlier than this, the "Canon of Medicine", written in the 10th Century by the Persian doctor and scholar Avicenna, mentions symptoms and treatment. Herod the Great is a famous example, whom many believe to have died in the 4 B.C. from Fournier gangrene.

Introduction and definition

When Jean Alfred Fournier published his article in 1883 on "Catastrophic gangrene of the penis", he postulated three key aspects:

Sudden onset in otherwise healthy young men with a rapid progression to advancing gangrene, without any definitive cause for the disease being determined.

This latter aspect in particular marked the crucial difference from the cases that had been described to date: no cause could be found. In the case described by Baurienne, an injury caused by the horns of a cow was the reason for the development of gangrene. Alfred Fournier is therefore actually the first person to describe idiopathic gangrene.

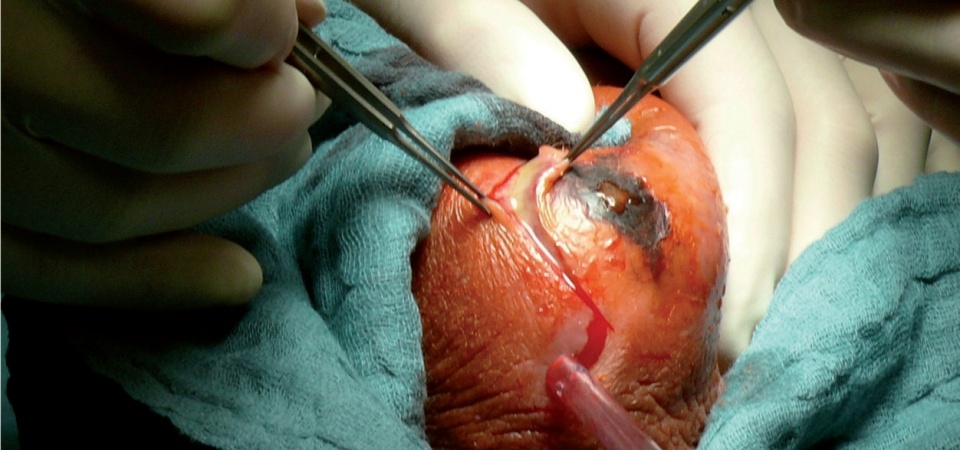

Findings following necrectomy, further procedures will certainly need to be carried out at a

later date.

Findings following necrectomy, further procedures will certainly need to be carried out at a

later date.

The terminology of Fournier gangrene and its definition from 1883 has been debated over and over again. At the time it was first described, no cause for the infection could be found - however now, around 130 years later, research and methods have advanced considerably and processes of unknown genesis are extremely rare. In order to reflect every aspect and all the knowledge of our era, all kinds of classifications have been created and rejected in an attempt to correctly classify Fournier gangrene in the modern context. These include classification into primary and secondary forms of the infection, for example, with the term 'primary' being reserved for idiopathic occurrences. The main point of contention still revolves around the obligatory presence - or absence - of an infection at the time the gangrene develops.

An infection as a cause of gangrene is now assumed to be present in every case, with some authors calling for the term Fournier gangrene to be dispensed with altogether and instead the term 'infectious gangrene of the genitalia' to be used. The term is firmly rooted in everyday clinical practice, however, and Fournier's disease is today usually - and in literature - defined as a particular form of infectious, necrotising fasciitis affecting the perineal, perianal and scrotal regions.

Clinical examination and diagnosis

Gangrene can essentially occur in men as well as in women and children, although the ratio is weighted unfavourably for men at 10:1. Incidence is low, with around 1.6 cases per 100,000 men reported a year. One major study reports a mortality rate of 16%.

The diagnosis is classically made on a clinical basis and the condition must be spotted early and treated immediately by an experienced clinician. The picture is one of fulminant necrosis with associated sepsis; frequently it begins with just a small skin lesion and often the gangrene spread in just a few hours. The necrosis becomes increasingly demarcated, initially red and livid and then almost black. In up to 40% of cases, the condition progresses slowly, so intensive monitoring of the patient is important. There is local oedema, indurations, crepitations, pain and often a strong, acrid odour. Fever, rigors and raised inflammatory parameters on laboratory testing are also present. In brief, the signs are those of severe systemic disease or sepsis.

Radiological methods can be useful, for example in order to detect subcutaneous pockets of gas or abscesses as a source of infection.

Following initial treatment, it is important to determine the causes of the gangrene and resolve these.

Aetiology

Risk factors for the development of Fournier gangrene include systemic as well as local processes. Favourable underlying systemic conditions include diabetes mellitus and alcoholism, which are present in up to 20 - 70% and 20 - 50% respectively of patients with gangrene. Other conditions include leukaemia, malignancies, chronic steroid abuse, under-nutrition and HIV infections. HIV has been on the increase since the 1990s and is the cause of a significantly higher prevalence of gangrene in African countries. Impaired cellular defences can be defined as a culprit common feature.

Local entry sites are, in descending frequency, the skin, the gastrointestinal tract and the genital and urinary tract. Fournier gangrene can occur following surgery, injuries and diseases especially, such as in some cases following vasectomy for example, in cases of renal or rectal abscess, ureteric stones and strictures with extravasations and ruptured appendices, diverticulitis and colon carcinomas.

Pathological mechanism

Once pathogens have entered the body, a self-sustaining cascade develops (from the site of entry). In most cases, the samples collected show mixed cultures of aerobic and anaerobic commensal flora such as Clostridia, Klebsiella, Streptococci, Coliforms and Staphylococci. Through synergetic effects, one bacterium creates the basis for the next, which in turn excretes leucocyte toxins and therefore supports the further proliferation of bacteria. Aerobes and their consumption of oxygen create a breeding ground for anaerobic bacteria. Endarteritis obliterans leads to vascular thrombi of smaller skin and subcutaneous vessels and therefore to necrosis. The natural circulation stops. The further migration and function of leucocytes is therefore stopped, so bacteria are able to "devote themselves" to their cell cycle in this ideal medium. This creates a vicious circle, which is also made worse by the local hypoxia. Skin necrosis continues quickly as a result of ischaemia and the synergistic effects of bacterial flora, although generally speaking the pathogens have a low virulence. It is postulated that the interaction of the primary affect, host immunity and the spectrum of pathogens leads to infections of this extent.

Treatment

The treatment mantra remains as previously: prompt, radical surgical debridement with antibiotic broad-spectrum therapy in an intensive care environment. Surgical intervention should take place within the first 24 hours, since this significantly increases the chances of survival. During surgery, necrosis is often seen down to the underlying fascia; involvement of the muscles is more rare, and it is very rare that the testes are also affected. Frequently, however, the extent of the necrosis is larger than it outwardly appears. To begin with, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment in the form of triple therapy effective against anaerobes, Streptococci, Staphylococci and Coliform is recommended. If cultures are obtained from blood and swabs, these antibiotics can be adjusted accordingly.

Necrotising fasciitis, according to the Association of German Pressure Chamber Centres, is a condition for which adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy is urgently recommended. The mechanism of effectiveness involves reducing the hypoxic dysfunction of leucocytes, the direct inhibition of anaerobic bacteria and improved penetration of the antibiotic into bacterial cells. This treatment is disputed in the European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines, however, and reserved for treatment in the context of studies. Added to this is the limited availability of pressure chambers in Germany.

Case example from clinical practice: Fournier gangrene following an incontinence tape implantation

Following plastic coverage and

reconstruction of the scrotum.

Following plastic coverage and

reconstruction of the scrotum.

A 67-year-old patient presents with a fever up to 38.8 °C and rigors to our emergency admissions unit. That very morning he had been discharged well from the ward after having undergone the trans-obturator implantation of an incontinence tape five days previously. From the patient's history, he is known to have type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient developed a septic infection following a prostate punch biopsy two years earlier. Otherwise there were no known immuno-compromising conditions and the patient was not on any immuno-modulatory medications. On admission, the perineal scar was quiescent. The testes exhibited a haematoma following surgery and ultrasound showed a small amount of peri-testicular oedema, but was otherwise unremarkable. There was a leucocytosis of 17.6*103/ul and a CRP of 17.05 mg/dl. The urine was negative. Despite antibiotics, initially with cefuroxime, then escalating to levofloxacin, the patient's inflammatory parameters increased. CT showed no abnormal findings. Blood cultures initially remained negative. Within one day, the patient's scrotal oedema worsened, the scrotal skin became progressively more livid in colour and started to necrose, resulting in the decision to proceed to immediate necrectomy. Following radical debridement of the necrotic tissue, both testes were in their sacs, the root of the penis with the urethra and the anal sphincter were clear; during the procedure the patient required catecholamines and subsequent transfer to the intensive care unit. Wound swabs taken during the procedure showed coagulase-negative Staphylococci, including Staph. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecium and the anaerobe Bacteroides capillosus. The antibiotic therapy which had up to that point included Meronem and metronidazole was changed to reflect the bacterial resistances. Blood culture also now showed a pathogen reservoir of Streptococci and Staphylococci. Following debridement, the laboratory parameters quickly normalised and the patient was extubated four days later. On the sixth post-operative day he was transferred to the normal ward. During his stay on the intensive care unit, he was transfused with one unit of red cell concentrate and four units of FFP. In total, the patient's admission extended over 76 days; a single scrotectomy and necrectomy was carried out, an interpolated skin flap graft was performed and followed by multiple split skin and full skin grafts. A temporary relocation of the testes below the inner skin of the thigh was needed and their return and plastic reconstruction of the scrotum was carried out four months later.

The patient is now fully rehabilitated and has been supplied with an artificial sphincter system.

Summary

Old sources of infection at the time of Baurienne and Fourier are increasingly losing their significance; other risk factors, however, are on the rise as a result of population ageing and multi-morbidity. Also of note are the persistently high rates of people with HIV infection on the African continent. It is also important not to overlook occult processes and cases involving women and children. Rapidly advancing necrosis associated with a septic picture should prompt every clinician to consider Fournier gangrene.

Author:

Nina Sinthofen, Surgeon Major

Central Military Hospital, Coblenz

Dept. XI - Urology

Date: 07/08/2019

Source: Medical Corps International Forum (4/2015)