Article: Dr. Lasse Hebsgaard, MD

COLLECTIVE EXPERIENCE WITH ULTRASONOGRAPHY AMONGST PHYSICIANS IN THE DANISH ARMED FORCES AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this paper is the authors’ alone and does not reflect the opinions of the Danish Armed Forces or Medical Command.

INTRODUCTION

The use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in both Emergency Departments(1) and, to a lesser degree, General Practice is growing into the new normal in the Danish health care system. We define POCUS as bedside ultrasonography, often answering dichotomic questions in relations to confirming or ruling out a diagnosis, or guiding an invasive procedure. More and more junior doctors undergo undergraduate ultrasound training(2) and put their skills to daily use in their clinical basic training (1st post graduate year clinical rotations), continuing into specialty training. Use of POCUS in the prehospital setting has been shown to change patient management, however, no change in outcome have been demonstrated, although it does not seem to do any harm either(3,4)

The Danish Defense Medical Command does not currently have a policy on education, use, and distribution of ultrasound equipment throughout the Armed Forces’ medical facilities. Through the last decades, ultrasound equipment has been assigned to various units on demand, however, no general implementation strategy has been proposed. The general implementation of POCUS in the Danish Armed Forces have been suggested in the past. Contemporary ultrasound diagnostics and improvements in diagnostic possibilities and abilities may improve recruitment as well as patient management. However, no final decision has been made on the matter.

Advantages of POCUS as a part of the treatment algorithm in the medical treatment facilities includes, but is not limited to, fast intravenous access in the difficult setting, Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) and Focused Assessed Transthoracic Echocardiography (FATE). Moreover, in less urgent situations, POCUS is helpful in bone and tendon damage diagnostics, tendinitis, abscesses, gall stones and more(5). With implementation of ultrasound in the Danish Armed Forces, implications in form of need of education, training and maintaining skills will follow acquisition of equipment. A focused education can give the user tools for decision making in situations with doubts regarding the diagnosis(6,7).

In order to plan further targeted education in POCUS for the doctors of the Danish Armed Forces, we need to establish their collective experience with sonography. Medical doctors of the Danish Armed Forces come from many different backgrounds, levels of experience and specialties. All are recruited from the civilian health care system. No record of ultrasound experience amongst these doctors exists.

The aim of this study is to characterize the population of medical doctors associated to the Danish Armed Forces with regards to specialty, experienced with ultrasound and medical practice in general, in order to illuminate the need for resources in implementation of ultrasound in the Danish Armed Forces.

METHODS

This cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted as an anonymized questionnaire to determine the level of experience in medicine and ultrasound, as well as distribution of specialties and relation to the Armed Forces. For most answers, it was possible to submit a custom written answer to specify any doubts.

A link to the internet-based questionnaire was sent to full time military employed medical doctors (n=56) by regular or confidential mail, which meant participants had to forward the link to an internet-based device. Reservist doctors (n=256) received the link by text message, and were able to access the questionnaire directly on their smartphone. The online form was open for responses from November 6th until December 7th 2023. Two to three reminder messages were relayed to all eligible participants during that period.

In a reach-out in our international military medical network, colleagues provided information on availability of ultrasound and education provided in their Armed Forces.

Data collection was completed with Google Forms, analysis and illustrations were performed AI-assisted (OpenAI ChatGPT), using Microsoft Excel, to show distributions.

RESULTS

From a total of 312 possible participants, 162 respondents yielded 158 complete questionnaires, equal to a response rate of 52 percent. Sixty-one and a half percent of respondents were reservists (main occupation in the civilian health care system), 14.9 % were junior military physicians (2-year Army contract employment), 12.4 % were primarily occupied in the base medical treatment facilities and 11.2 % had staff functions or similar, primarily administrative, function. Across respondents, experience in medical practice ranged from 2-48 years, with an average of 16 years (median±SD 15±10) since medical school graduation.

The main part of the participants was those specialized, or pursuing a career, in anesthesia (42.6 %), followed by Family Medicine (13 %), Orthopedic Surgery (8.6 %), Undecided (junior doctors, 6.8 %), Abdominal Surgery (6.2 %), Emergency Medicine (4.9 %), and Thoracic Surgery (3.1 %). Remaining respondents were distributed between other specialties.

Half of the repondents had an experience of 5 years or more using ultrasound, 12 % had no experience, and the remaining ranged from 1 to 5 years of experience.

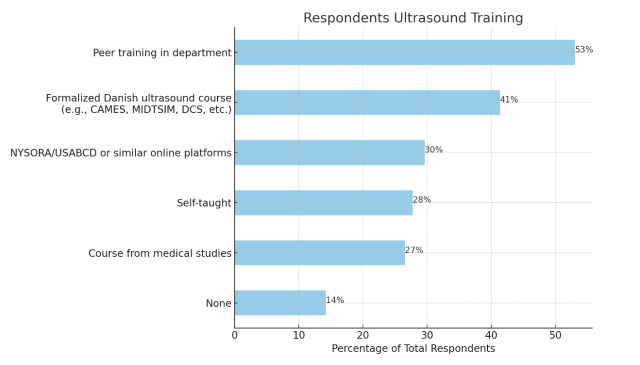

As presented in figure 1, most participants had one or more type of training in ultrasonography. Only 14 % reported no ultrasound training.

Figure 1 - Types of ultrasound training reported by respondents

Having no experience with ultrasound did not appear to result in a negative attitude towards implementation, as there is only a non-significant (p=0.268), weak correlation coefficience of 0.088.

When looking at the subpopulation of junior military physicians, the recruitment base for the reserve and full time employment, all reported some kind of ultrasound training (Table 1).

Table 1 – Ultrasound training in subpopulations

Training | Senior full-time military physicians | Junior military physicians | Reservist physicians |

None | 31 % | 0 % | 12 % |

Self-taught | 14 % | 38 % | 31 % |

Peer training in department | 41 % | 83 % | 52 % |

Course from medical school | 3 % | 62 % | 25 % |

NYSORA/USABCD or similar online platforms | 10 % | 17 % | 39 % |

Formalized Danish ultrasound course (e.g. CAMES) | 24 % | 33 % | 48 % |

Our respondents were, on average, familiar with 3 different ultrasound examinations(excluding those answering “other/non”). Ultrasound guided vascular access and eFAST was familiar to around 60 % each. Periferal nerveblock was mentioned as free text answer by 10 % (Table 2).

Table 2 - Ultrasound exams or procedures known to respondents

Ultrasound exam or procedure | No. familiar with procedure | % of total respondents |

eFAST | 97 | 59,5 |

Vascular access | 96 | 58,9 |

FATE | 72 | 44,2 |

FLUS | 55 | 33,7 |

Abdominal | 42 | 25,8 |

Musculoskeletal | 32 | 19,6 |

Vessels | 28 | 17,2 |

Gynecological | 27 | 16,6 |

Echocardiography | 22 | 13,5 |

Peripheral nerve block | 15 | 9,2 |

|

|

|

Others or non | 27 | 16,6 |

Average no. of exams/procedures known to respondents | ||

Total answers | 513 | 3 |

Total respondents | 162 |

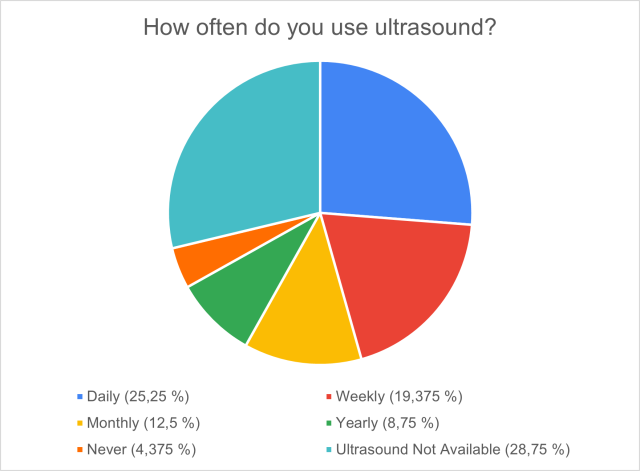

A quarter of the respondents use ultrasound on a daily basis, a third does not have ultrasound at their disposal. A fifth use it every week and only 4.4 % never use it (figure 2).

Figure 2 - Frequency of ultrasonography usage

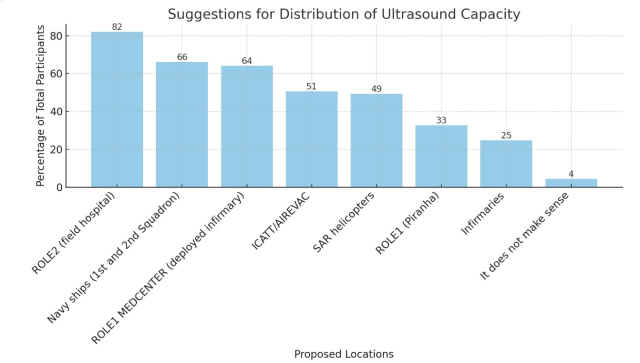

Of all respondents, 96 % were positive towards implementation of some form of ultrasound in the Armed Forces. Implementation of ultrasound capacities was most wanted in the Role 2 (small field hospital, defined in NATO doctrin(8)) with 82 % follow by Navy ships and deployed medical center/base infirmary with two thirds each. Half of respondents wanted ultrasound allocated to the Intensive Care Transportation Team/aireal evacuation unit (ICATT/AIREVAC) capacity and Search And Rescue (SAR) helicopters, one third to the front line Role 1 (aid station) and a quarter to the home-base infirmaries (figure 3).

Figure 3 - Suggestions for distribution of ultrasound equipment by all respondent

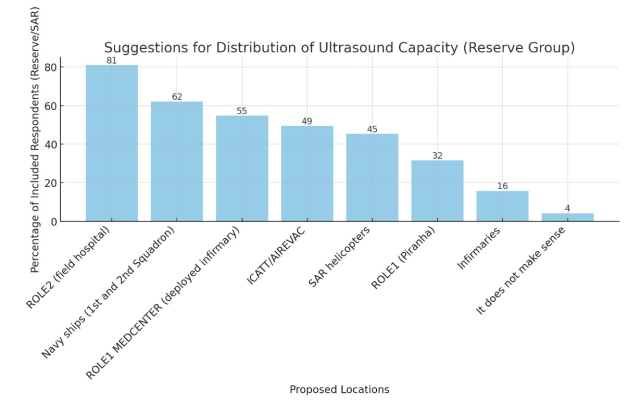

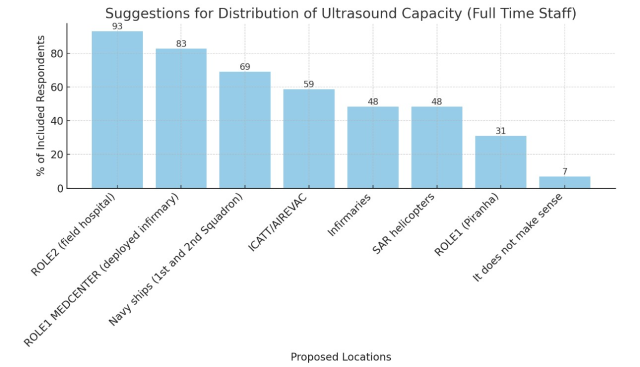

A similar distribution was found amongst reserve group doctors (figure 4), whereas full time senior staff (figure 5) ranked deployed and base infirmaries higher.

Figure 4 - Suggestions for distribution of ultrasound equipment by reservist doctors

Figure 5 - Suggestions for distribution of ultrasound equipment by full time staff physicians

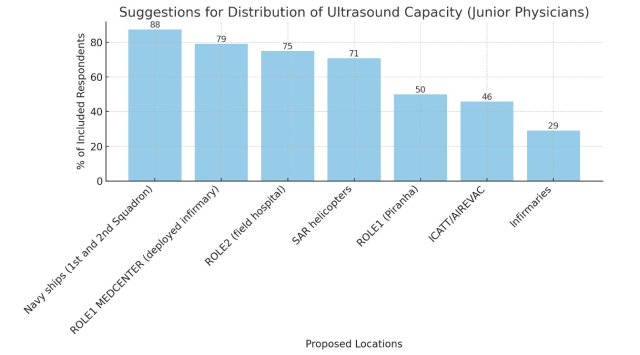

Junior physicians (figure 6) all found ultrasound useful in some capacity, with most (88 %) wanting availability on Navy ships and fewest (29 %) in base infirmaries.

Figure 6 - Suggestions for distribution of ultrasound equipment by junior military physicians

Table 3 shows the placement of ultrasound capacity in some of our allied military health care systems. Germany, Netherlands, France, and Belgium provide a minimum of a basic ultrasound course for their active duty physicians.

Table 3 - distribution of ultrasound equipment at allied military health care providers

GERMANY | THE NETHERLANDS | ENGLAND | FRANCE | SPAIN | ITALY | BELGIUM | |

ROLE1 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

ROLE2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

MEDEVAC | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

BASE HOSPITAL | x | X | x | ||||

CASUALTY STAGING UNIT | X |

DISCUSSION(PERSPECTIVES)

This study was a first attempt of mapping military affiliate physicians’ experience and competences. Although we hoped for higher numbers, considering the selected group of possible partissipants, the reponse rate of 52 % is in agreement with the anticipations during the study planning and compare to average online survey response rates.(9)

It is continuously debated in the Danish Armed Forces, whether POCUS is a necessary, procedure, depending on the setting. In general, we found a positive attitude towards implementation across all branches and functions.

Curricula for POCUS are introduced to residency programs internationally in association with several medical schools(10–13). Some of our allied countries (mentioned above) have ultrasound capacity available in Roles 1 and 2 and in MEDEVAC (medical evacuation) units, and provide a basic ultrasonography course for their health care providers. As NATO allies, it is the opinion of the authors, that Roles should be comparable in diagnostic capacities.

Resources in the form of time for hands-on training and experts for supervision remain an issue. Serious Games (games designed specifically for learning and not for entertainment) has been proposed as a way of mitigating this problem with promising results, showing improvement in image acquisition in early ultrasound training(14). Feasibility of remote tele-supervision of ultrasound operators has been proven in the hospital setting for a commercially available, low-cost setup(15). Internet connection in the remote setting of a ship in the North Atlantic Ocean, for example, remain an obstacle to telemedicine with the data volume necessary for proper image quality. However, this may change with future satellite-based connections.

Due to the high numbers of (junior) physicians reporting prior ultrasound experience and education, resources can be directed towards maintenance and expansion of skills. Ultrasound courses and availability of equipment may also help in recruiting and retaining physicians in the Armed Forces. As ultrasound is a readily available tool in the civilian setting, and the Armed Forces highly relying on reservist, it is a concern, that this is a missing tool in the box, when they enter the military system, however short or long. Ultrasonography is by some compared to the stethoscope: “if auscultation is indicated in certain cases, it is still true in the austere setting, where noise makes it impossible, however, this can be somewhat replaced by ultrasound”.

Free-text comments were submitted by 25 % of the respondents. Comments include short, positive statements as “indispensable”, “ultrasound is the future”. Most are positive towards the implementation of ultrasound in the Armed Forces under the condition, that proper education and maintainance of skills are prioritized. Some are sceptics and see advantages limited to field hospitals and missions at sea. And still then, they find, that the cost outweigh the benefits, if you are properly trained in interpreting patients’ signs and symptoms. The flow of patients is low and loss of clinical skills is to be expected during long-term employment with less patient contact, than in the civilian health care setting. Some mourn the loss of ultrasonography skills due to the lacking of equiptment.

The patient benefit of POCUS in the prehospital setting remains to be scientifically proven, however, diagnostic discission making may be supported by POCUS in austere environments(16). Of an all-comer population in a Danish Emergency Department, 27 % were shown to benefit from POCUS (confirmation of diagnosis or change in management), predicted by triage level, abdominal pain, or certain preexisting comorbidities(17). POCUS may be helpful on the frontline in triage and resource management, for instance, for monitoring victim of traumatic brain injury by proxy of optic nerve sheath diameter(18) and has potential for improving care of the soldiers in the front line(19–21).

Implementation of ultrasonography should be followed by a basic ultrasound course to provide military staff with familiarity of the chosen system, as well as refreshing knowledge from previous education. In order to maintain skill, ultrasound capacities, should be readily available throughout the military health care system. This would allow for daily use on all levels of care. However, when prioritizing, equipment should be placed where it may provide most benefit for the patient: the remote setting of sea or land deployment.

The next order of business, when implementation have been decided, is to choose the ultrasonography system. For a system to be able to operate in all settings mentioned, it must be durable, mobile, small size, light weight, and preferably battery operated(22). The system specifications should be chosen by the operational units, and only provided to the training units and base medical facilities.

Preferably, the same system should be available across units to minimize resources used on training in handling different systems.

STUDY LIMITATION

It is reasonable to assume a degree of sample bias - or non-response bias - as sceptics might be reluctant to respond and hence, pro-ultrasound respondents may be overrepresented. This could be enhanced by the description of the survey, where we mentioned the use of the results to promote implementation.

Self-reported information on education and experience with ultrasound is no guarantee of actual capabilities. However, anonymity of the questionnaire might have reduced this bias.

CONCLUSION

In general, this study found a positive attitude towards implementation of ultrasound in the Danish Armed Forces amongst the survey respondents. The reported level of education and experience were high, which may reduce resources needed in the implementations process. Furthermore, the implementation of modern diagnostic tools that reassemble civilian capacities may have a positive influence on recruitment of junior doctors.

Decisions remain to be made on how to maintain skills and where to provide ultrasound capacities in order to maximize effect.

REFERENCES

1. Arvig MD, Laursen CB, Weile JB, Tiwald G, Graumann O, Posth S. Point Point of of care-UL-skanning i care-UL-skanning i danske danske akutafdelinger akutafdelinger. Vol. 183, Statusartikel Ugeskr Laeger. 2021.

2. Pedersen RG. Medicinstuderende fra SDU bliver de bedste til klinisk ultralyd. [cited 2023 Oct 10]; Available from: https://www.sundoghed.dk/18172/medicinstuderende-fra-sdu-bliver-de-bedste-til-klinisk-ultralyd/

3. Bøtker MT, Jacobsen L, Rudolph SS, Knudsen L. The role of point of care ultrasound in prehospital critical care: A systematic review. Vol. 26, Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2018.

4. Osterwalder J, Polyzogopoulou E, Hoffmann B. Point-of-Care Ultrasound—History, Current and Evolving Clinical Concepts in Emergency Medicine. Medicina (B Aires) [Internet]. 2023 Dec 15;59(12):2179. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/59/12/2179

5. Hashim A, Tahir MJ, Ullah I, Asghar MS, Siddiqi H, Yousaf Z. The utility of point of care ultrasonography (POCUS). Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2021 Nov 1;71.

6. Lindgaard K, Riisgaard L. ‘Validation of ultrasound examinations performed by general practitioners.’ Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017 Jul 3;35(3):256–61.

7. De Carvalho H, Godiveaux N, Javaudin F, Le Bastard Q, Kuczer V, Pes P, et al. Impact of Different Training Methods on Daily Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound: Survey on 515 Physicians. Ultrasound Q [Internet]. 2023; Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ultrasound-quarterly/fulltext/9900/impact_of_different_training_methods_on_daily_use.50.aspx

8. NATO. https://www.nato.int/docu/logi-en/1997/lo-1610.htm. 1997. NATO Logistics Handbook.

9. Wu MJ, Zhao K, Fils-Aime F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports. 2022 Aug 1;7.

10. Mellor TE, Junga Z, Ordway S, Hunter T, Shimeall WT, Krajnik S, et al. Not just hocus POCUS: Implementation of a point of care ultrasound curriculum for internal medicine trainees at a large residency program. Mil Med. 2019 Nov 1;184(11–12):901–6.

11. Perrier P, Leyral J, Thabouillot O, Papeix D, Comat G, Renard A, et al. Usefulness of point-of-care ultrasound in military medical emergencies performed by young military medicine residents. BMJ Mil Health. 2020 Aug;166(4):236–9.

12. Geis RN, Kavanaugh MJ, Palma J, Speicher M, Kyle A, Croft J. Novel Internal Medicine Residency Ultrasound Curriculum Led by Critical Care and Emergency Medicine Staff. Mil Med. 2023 May 16;188(5–6):e936–41.

13. Martin R, Lau HA, Morrison R, Bhargava P, Deiling K. The Rising Tide of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) in Medical Education: An Essential Skillset for Undergraduate and Graduate Medical Education. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol [Internet]. 2023;52(6):482–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0363018823000890

14. Olgers T, Rozendaal J, van Weringh S, van de Vliert R, Laros R, Bouma H, et al. Teaching point-of-care ultrasound using a serious game: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Dec 1;23(1).

15. Jensen SH, Duvald I, Aagaard R, Primdahl SC, Petersen P, Kirkegaard H, et al. Remote Real-Time Ultrasound Supervision via Commercially Available and Low-Cost Tele-Ultrasound: a Mixed Methods Study of the Practical Feasibility and Users’ Acceptability in an Emergency Department. J Digit Imaging. 2019 Oct 15;32(5):841–8.

16. Dana E, Khan JS, Kpa’Hanba GA, Nour ADM. Point-of-Care Ultrasound (PoCUS) and Its Potential to Advance Patient Care in Low-Resource Settings and Conflict Zones. Disaster Med Public Health Prep [Internet]. 2023/06/22. 2023;17:e417. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/98E72011BB96FB873F0EF32C331BDD9A

17. Weile J, Frederiksen CA, Laursen CB, Graumann O, Sloth E, Kirkegaard H. Point-of-care ultrasound induced changes in management of unselected patients in the emergency department - A prospective single-blinded observational trial. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020 May 29;28(1).

18. Nathani A, Ghamande SA, Kambhampati S, Anderson B, Lohse M, White HD. The Use of POCUS-Obtained Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. POCUS Journal. 2023 Nov 27;8(2):170–4.

19. Balasoupramanien K, Comat G, Renard A, Meusnier JG, Montigon C, Pitel AS, et al. Ultrasonography Performed by Military Nurses in Combat Operations: A Perspective for the Future? J Spec Oper Med. 2022 Sep 19;22(3):65–9.

20. Snyder R, Brillhart DB. Pain Control and Point-of-Care Ultrasound: An Approach to Rib Fractures for the Austere Provider. J Spec Oper Med. 2023 Oct 5;23(3):70–3.

21. Savell SC, Baldwin DS, Blessing A, Medelllin KL, Savell CB, Maddry JK. Military Use of Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS). J Spec Oper Med. 2021;21(2):35–42.

22. Gharahbaghian L, Anderson KL, Lobo V, Huang RW, Poffenberger CM, Nguyen PD. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Austere Environments: A Complete Review of Its Utilization, Pitfalls, and Technique for Common Applications in Austere Settings. Emerg Med Clin North Am [Internet]. 2017;35(2):409–41. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0733862716301213

LIST OF AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS

Dr. Lasse Hebsgaard, MD

1st Lieutenant, Medical Doctor, Junior Physician, Danish Defense Medical Command

Resident, Department of Anesthesia, Aarhus University Hospital

E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +45 2183 2412

Biography: Dr. Hebsgaard has experience from general practice, internal medicine, cardiology, and anesthesiology. Before entering the residency program for anesthesiology at Aarhus University Hospital, Dr. Hebsgaard served two years as military physician in the Danish Armed Forces, and is still attached to the Search-And-Rescue branch of the Royal Danish Air Force.

Dr. Karsten Lindgaard, MD

Major, Medical Doctor, Consultant in in Family Medicine and Aviation Medicine, at Danish Defense Medical Command’s Aviation Medicine Center

E-mail: [email protected]

Conflicts of interest: Nothing to declare.

Date: 07/24/2024