Overview: Hyoung Gi Kim

Status and success rate of smoking cessation treatment patients in the ROK front-line Infantry Division

Office of Human Resources Development, Armed Forces Capital Hospital, Armed Forces Medical Command, Seongnam, Korea.

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

Introduction

The Republic of Korea is the only divided country in the world, and about 1.5 million troops from North and South Korea are facing each other around the armistice line, and for this purpose, most healthy adult males are conscripted into the military in their early 20s and have to perform 18~20 months of compulsory service. In the past, the ROK military lacked social awareness of cigarettes to the extent that duty-free cigarettes were given to soldiers as their favorite food. Smokers believed that cigarettes alleviated combat stress and encouraged their successors to smoke, but smoking leads to dysregulation of the brain's stress system. (1) Smoking has a very direct negative effect on oral health. It is known that 90% of oral cancer patients have a history of smoking, and smokers have a higher incidence of oral cancer than non-smokers. (2) In addition to these well-known health hazards, tobacco presents a tactical weakness for the military

Cigarette lights are identified from 2,000 meters away at night in no moonlight, which is very disadvantageous to maintaining the secrecy, which is one of the most important things in tactics. Recently, in the Ukraine-Russia war, a video of a sniper spotting and killing an enemy with the light of a cigarette has been posted, So, Smoking cessation has been on the rise in the military for tactical purposes as well as health purposes. Moreover, if we calculate the average daily intake of 12.6 cigarettes (3) and the average number of inhalations per cigarette of 20.4 times(4), A soldier who smokes exposes his position to the enemy about 460 times a day. In addition, tobacco affects basic physical strength such as cardiorespiratory endurance, which also adversely affects combat power.(5) Therefore, the smoking cessation of service members is very important than that of civilians, The smoking rate of Korean soldiers was 40.7 percent in 2019, which is higher than the smoking rate of adult males of 35.7 percent during the same period.(6)

In the this paper, in order to protect the health of the soldiers of the front-line infantry divisions and their precious lives in wartime, smoking cessation treatment was carried out mainly by the border units (GP, GOP, division reconnaissance battalion), and the current situation and smoking cessation success rate were analyzed retrospectively. In addition, we propose effective anti-smoking policies that can be implemented in the military.

Methods

1. Research Design

This study is a prospective study to analyze the current status of smoking cessation treatment patients in the frontline infantry division and identify the factors affecting the smoking cessation success rate. Varenicline and bupropion were used as drugs, and no supplements such as nicotine patches and gum were used.

From May 15, 2023 to February 26, 2024, 337 soldiers of the 15th Infantry Division stationed on the Central Front in Gangwon-Do Province were treated for smoking cessation. Medications were varenicline and bupropion, and no supplements such as nicotine patches and gum were used.

2. Subject of study

The subjects of this study were 337 soldiers of the frontline infantry division stationed in the central front of Gangwon-do who wished for smoking cessation treatment from May 15, 2023, to February 26, 2024. The GP, GOP, and Division reconnaissance battalions engaged in intensive confrontation with the enemy were classified as border units, while the rest of the units were classified as regular units. Leaders below platoon leader and other positions in infantry branch that fought in close proximity to the enemy on the front line were classified as combatants, artillery, communications, and other branches that supported operations in the rear of the front line, and commanders above company commander were classified as combat support.

In addition, the classes of the study subjects were classified into soldiers and officers. The current status of smoking cessation treatment patients was analyzed for 337 patients, and the factors affecting the smoking cessation success rate were analyzed for 108 patients who had follow-up observations more than once out of 337.

3. How and what to collect data

Patient visits were either visit or outpatient. Smoking cessation treatment was advertised in advance through the personnel system and those who wished to receive treatment were recruited. The GP, GOP, and Division reconnaissance battalions engaged in intensive confrontation with the enemy were classified as border units, while the rest of the units were classified as regular units. Commanders below platoon leader and other positions in infantry branch that fought in close proximity to the enemy on the front line were classified as combatants, artillery, communications, and other branches that supported operations in the rear of the front line, and commanders above company commander were classified as combat support. The rounds were conducted for GP, GOP, Division reconnaissance battalion operation company and Recruit Training Battalion, and GP, GOP, and Division reconnaissance battalion operation company were visited approximately every 5 weeks, and the Recruit Training Battalion was visited every 4 weeks. Outpatient treatment was advertised on the division's website and was conducted at intervals of about three weeks for those who wished. The age at which smoking cessation started, nicotine dependence, daily smoking amount, smoking experience and duration of quitting, cause of failure, motivation for quitting, and subjective intention to quit smoking (0 ~ 10 points) were checked through questionnaires at the time of first visit. Nicotine dependence was determined using the Fagerstrom Nicotine Dependence Test (FTND, 0 ~ 10). The success criterion was that smoking cessation was judged to be successful if the patient had quit smoking 7 days prior to the visit, and the nicotine urine test was not performed and the patient's statement was relied upon.

4. Data Analysis Method

In order to confirm the current status of smoking cessation treatment, the general characteristics of the subjects between the two groups and the past smoking cessation experience were compared and tested in the unit type (contact unit/general unit) and class (soldiers/ NCOs and officers), respectively. Wilcoxon rank test was applied to continuous variables such as age, and Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was applied to categorical variables such as smoking cessation motivation.

Factors influencing the success of smoking cessation were identified in 108 subjects who were able to confirm the success/failure of smoking cessation by observing the course at least once among the study subjects. Influencing factors were unit type (contact unit/general unit), position (combat/combat support), class (soldiers/officers), attempt to quit smoking, motivation to quit smoking, cause of failure to quit smoking, age, first smoking age, smoking year, daily smoking amount (pack), nicotine dependence and subjective will to quit smoking. The association between influencing factors and smoking cessation success rate was confirmed by logistic regression analysis and applied in both short-variable analysis and multi-variable analysis. The selection of variables included in the multi-variable analysis was determined by the p-value<0.1 factor of the single-variable analysis. Among the influencing factors, unit type (contact unit/general unit), position (combat/combat support), class (soldiers/ NCOs and officers), and age are similar concepts, and multi-collinearity is high, so the unit type and class are selected. The multi-collinearity of the multi-variable analysis was confirmed by a variance inflation factor (VIF).

Results

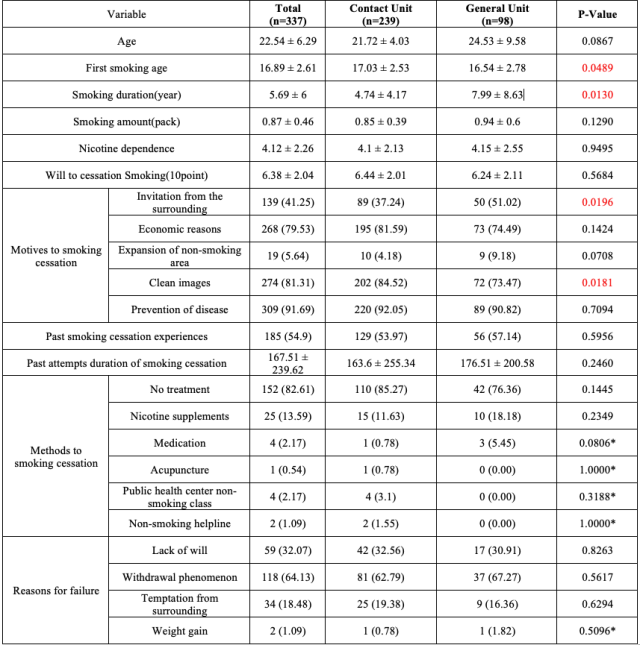

- Comparison of general status and past smoking cessation experience of non-smoking patients (table 1, 2, 3)

The total number of patients was 337, 239 for contact units and 98 for general units by unit type. 276 for soldiers and 61 for NCOs and officers. 199 for combat positions and 138 for combat support positions.

In all 337 patients, the average age was 22.54 (standard deviation 6.29), and the first smoking started at 16.89 (2.61) years and the smoking period was 5.69 (6.00) years. They smoke 0.87 (0.46) packs per day and dependence on nicotine was high at 4.12 (2.26), but their willingness to quit smoking (out of 10 points) was also high at 6.38 (2.04). Motives to quit smoking were in the order of disease prevention (91.69%), clean image (81.31%), economic reason (79.53%), surrounding recommendation (41.25%), and expansion of non-smoking areas (5.64%). 54.9% of patients had attempted to quit smoking in the past and the average duration of attempt was 167.51 days (239.62). Among them, 13.59% of patients used nicotine supplements, but 82.61% of patients did not receive treatment. Withdrawal phenomenon (64.13%) was the most frequent failure to quit smoking, followed by will (32.07%) and temptation (18.48%).

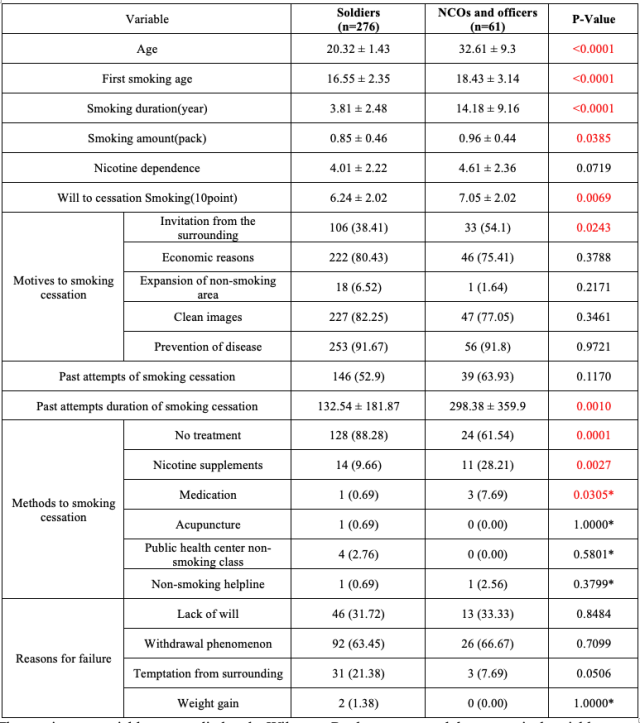

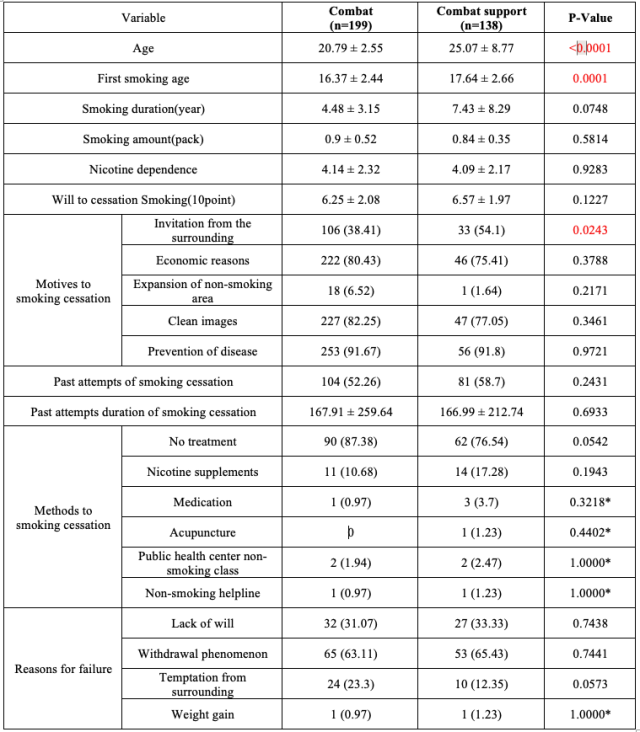

By unit type, rank, and position, the first smoking age of the contact unit was 17.03 (2.53) on average, and the first smoking age of the general unit was 16.54 (2.78) on average, showing a significant difference (p=0.0489). The smoking period (year) was 4.74 (4.17) for the contact unit and 7.99 (8.63) for the general unit, showing a significant difference (p=0.0130). When classifying by rank, there were significant differences in the most areas, and the first smoking age was higher in the NCOs and officers (18.43 (3.14) than in the soldiers (16.55 (2.35), and the smoking period was also significantly higher in the NCOs and officers than in the soldiers (p<0.0001) (in that order 3.81 (2.48), 14.18 (9.16); p<0.0001). In addition, they were smoking more in the NCOs and officers than in the soldiers (smoking volume (pack) = 0.85 (0.46) vs. 0.96 (0.44); p = 0.0385 (0.0385); and the past smoking cessation attempt period was longer in the NCOs and officers (298.38 (359.9 days) than in the soldiers (132.54 (181.87 days) (p=0.0010). The subjective willingness to quit smoking was higher among NCOs and officers than among soldiers (6.24 (2.02) points, 7.05 (2.02) points in order; p=0.0069) As a motivation for quitting smoking, the proportion of surrounding recommendations was significantly higher among NCOs and officers (54.1% and soldiers = 38.41%) as a motivation for quitting smoking (p=0.024), and The smoking cessation treatment experience rate was 11.72% for soldiers and 38.46% for NCOs and officers, which was significantly higher for NCOs and officers. (p=0.0001) There was no significant difference in nicotine dependence and smoking cessation attempt rate between soldiers and NCOs and officers (table 2). When compared by position, the most significant difference was less than that by other unit types and ranks. (table 3) The first smoking age of combat positions was 16.37 (2.44), which was significantly lower than the first smoking age of 17.64 (2.66) for combat support positions.

Table 1 Comparison of general status of smoking cessation patients and past smoking cessation experiences by unit type

The continuous variable was applied to the Wilcoxon Rank sum test, and the categorical variable was applied to the Chi-Square test or the Fischer's Exact test (*)

Table 2 Comparison of general status of smoking cessation patients and past smoking cessation experiences by class

The continuous variable was applied to the Wilcoxon Rank sum test, and the categorical variable was applied to the Chi-Square test or the Fischer's Exact test (*)

Table 3 Comparison of general status of smoking cessation patients and past smoking cessation experiences by positions

The continuous variable was applied to the Wilcoxon Rank sum test, and the categorical variable was applied to the Chi-Square test or the Fischer's Exact test (*)

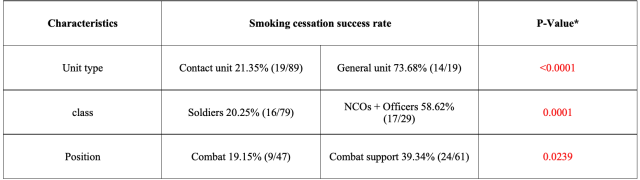

2. Non-smoking success rate (table 4)

Of the 337 patients who were analyzed, 108 patients underwent at least one follow-up observation, and the success rate of smoking cessation was analyzed only for them. The success rate of smoking cessation by drug was 30.7% (31 out of 101 successful) with varenicline and 28.5% (2 out of 7) with bupropion. On average, those who succeeded in quitting smoking succeeded in quitting within 21.7 days of receiving the drug. The success rate of smoking cessation by unit type (Table 4) was 21.3% (19 out of 89 successful) for the contact unit, significantly lower than the success rate of 73.7% (14 out of 19) for the general unit (p<0.001), and the success rate for quitting smoking by rank (Table 4) was significantly lower than the success rate of 20.3% (16 out of 79) for the soldiers (p<0.001) compared to the success rate of 58.6% (17 out of 29) for NCOs and officers (0.001). The smoking cessation success rate by position (Table 4) showed a statistically significant difference, with 19.1% (9 out of 47 successful) in combat positions and 39.3% (24 out of 61 successful) in combat support positions (p = 0.024)

Table 4 Comparison of smoking cessation success rate of non-smoking patients by characteristics

* Chi-square test

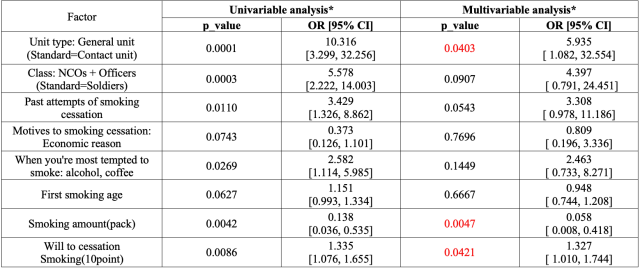

3. Factors influencing smoking cessation (Table 5)

The factors influencing smoking cessation were considered as unit type, position, rank, past quit attempt, motivation for quitting, cause of failure to quit smoking, type of medicine, age, age of first smoking, smoking period, amount of smoking (pack), nicotine dependence, and subjective intention to quit smoking, and the variables with p<0.1 of the single-variable analysis, unit type, and class were determined as variables that included the multi-variable analysis (data not shown). The variables to be included in the multivariate analysis were unit type, class, past attempts to quit smoking, motivation for quitting: economic reasons, causes of failure to quit: alcohol, coffee, age for first smoking, amount of smoking (pack), and subjective intention to quit. When the effects of the other variables were constant, the factors influencing smoking cessation success were unit type (p=0.0403), smoking amount (p=0.0047), and subjective willingness to quit (p=0.0421), and these variables were all significant in the single-variable analysis (p=0.0001, 0.0042, 0.0086, in that order).

Smoking cessation success odds were 10.32 times higher in the single-variate analysis in the general unit than in the contact unit (p<0.001,OR (95% CI) = 10.316.( 3.299-32.256), and was 5.94 times higher in multivariate analysis (p = 0.0403,OR (95% CI) = 5.935.( 1.082-32.554)). When the effects of the other variables are constant, smoking more than 1 pack per day is associated with a 0.058-fold lower probability of quitting (OR=0.058, 95% CI=0.008-0.418), and a 1-point increase in subjective confidence in quitting is associated with a 1.327-fold higher odds of quitting (OR=1.327, 95% CI=1.010-1.744). Although it was not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis, Smoking cessation success odds were 5.58 times higher in the single-variate analysis (p=0.0003,OR (95% CI)=5.578.( 2.222-14.003)). Those who had attempted to quit smoking in the past were 3.429 times more likely to succeed in quitting (p=0.0110,OR (95% CI)=3.429.( 1.326-8.862)). If they did not feel the temptation to smoke when drinking alcohol or coffee, they were 2.58 times more likely to quit smoking. (p=0.0269, OR (95% CI)=2.582. (1.114-5.985))

Table 5. Factors influencing smoking cessation

* logistic regression analysis in univariable and multivariable analysis

Discussion

The smoking cessation attempt rate was 54.9%, which was higher than the 52.6% of adult current smokers in 2016,(7) but there was no statistical difference (p=0.3986). The experience of treatment (including nicotine supplements) was very low at 16.8%. This is believed to be due to the lack of social awareness that smoking is a disease and promotion of smoking cessation treatment. A study by Song et al. found that the more people who have tried to quit smoking, the higher the success rate of quitting, and(8) It is known that smokers try to quit smoking 8~14 times on average to quit smoking.(9) Partos et al. reported that repeated failure to quit smoking due to a smoking cessation method that did not suit them may lead to low motivation or smoking cessation fatigue in the next attempt to quit smoking.(10)

In the this study, 82.2% of the soldiers who had tried to quit smoking in the past tried to quit smoking without any treatment and failed to quit smoking, so active smoking cessation treatment is necessary to break the cycle of repeated failures. In a study by Lee ES et al., it was found that the lower the nicotine dependence, the higher the success rate of quitting smoking,(11) and in this study, the higher the amount of smoking, the lower the age of first smoking, and the higher the nicotine dependence, the lower the success rate of quitting smoking. The higher the subjective willingness to quit, the higher the success rate of quitting.

Analyzing the difference between the smoking cessation success rate of the contact units and the general units, the average nicotine dependence of the contact units was 4.10, which was no different from the 4.15 of the general units (p = 0.95), but it is estimated that the reason why the smoking cessation success rate of the contact units is lower because they are stationed on the front line with less favorable conditions than the general units.

Analyzing the difference between the smoking cessation success rate of combat and combat support positions, the average nicotine dependence of combat positions was 4.14, which was no difference from 4.09 for combat support positions (p = 0.93), but the smoking cessation success rate of combat positions was significantly lower than that of combat support positions. Since the smoking cessation success rate of combat positions that are more vulnerable to enemy fire was significantly lower than that of combat support positions that are relatively safe in the rear, smoking cessation treatment should be given more emphasis on combat positions.

The reason why the success rate of NCOs and officers to quit smoking is 4.397 times higher than that of soldiers is that even though the amount of smoking is significantly higher among NCOs and officers, the subjective will to quit smoking is significantly higher among NCOs and officers, so it is judged that the influence of subjective will to quit smoking is greater than the effect of smoking amount.

I think the military is the best organization for smoking cessation for a variety of reasons.

First, the military is a very large organization. The larger the organization, the more interest there is likely to be in smoking cessation programs, and the lower the smoking rate,(12) but our military is a very large organization, with more than 500,000 members

Second, it is easy to encourage people to quit smoking.

Kang Yoon-sik reported that people who live with their families have a higher success rate of quitting smoking than those who do not,(13) and since soldiers share schedules in the same living space and take care of each other, there are more favorable conditions than other organizations in reducing the smoking rate of members. Many recruit training center, including Nonsan Training Center, are non-smoking for educational purposes. Just as all recruits live in the same way because they live in the barracks, the size of the organization is very large, and the rate of smoking cessation attempts increases on New Year's Day, according to Yumi's research, the rate of smoking cessation attempts increases after enlistment,(14) so it is most realistic to actively implement smoking cessation treatment, including smoking cessation drugs, at the recruit training institutions.

Third, it is an organization that exercises regularly. Regular exercise is known to help smokers quit.(15) Eunju Kwon reported that those who did not exercise had a 34% and 28% higher risk of recurrence at 3 and 6 months, respectively, than those who exercised.(16) In addition, exercise may reduce the risk of relapse in that it can alleviate the weight gain problems and withdrawal that may occur after quitting.(17)

Therefore, the military is the organization that has a higher need for smoking cessation than other organizations and at the same time is the best organization for the success of smoking cessation. Quitting smoking is also greatly beneficial economically. Individually, it will be possible to save 1.03 million won per year on cigarettes and protect health, and nationally, it will be able to contribute to reducing the financial expenditure on health insurance due to smoking, which is 3.02 trillion won as of 2022.(18)

In this study, those who succeeded in quitting smoking succeeded in quitting smoking in 21.7 days after receiving the drug on average, and the cost of varenicline for 21 days was 43,000 won. If you invest only about 43,000 won in medicine during the training period, you can expect to save 349,000 won (4,500 won x 365 days x 0.63 packs per day x 0.337 quitting smoking success rate of varenicline). In addition, the average smoking period of successful quitters is 22.87±12.29 years,(19) and considering that cigarette costs and medical expenses can be saved during this period, it is considered to be a cost-effective policy to focus on smoking cessation treatment during the recruit training period.

In this study, the number of follow-up people was small compared to the number of people who were analyzed. This is due to the characteristics of the army, personnel rotation such as transfer and transfer is very fast, the border units are stationed in a large area by small units, and it is often impossible to approach the units due to the rugged terrain and musical instruments, and the recruit training battalion is assigned to other divisions after completion. In the future, if more researchers are mobilized and thorough follow-up observation is carried out, it is judged that there will be high-quality research results.

Conclusion

The success rate of smoking cessation was higher in general units than in contact units, in NCOs+officers than in soldiers, and in combat support positions than in combat positions.

Reference List

1. Bruijnzeel AW. Tobacco addiction and the dysregulation of brain stress systems. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36(5):1418-41.

2. Znaor A, Brennan P, Gajalakshmi V, Mathew A, Shanta V, Varghese C, et al. Independent and combined effects of tobacco smoking, chewing and alcohol drinking on the risk of oral, pharyngeal and esophageal cancers in Indian men. International journal of cancer. 2003;105(5):681-6.

3. Agency KDCaP. 2020 Korean Cigarette Smoking Habits and Forms. 2020.

4. Agency KDCaP. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2021.

5. Guo Y. Nicotine dependence affects cardiopulmonary endurance and physical activity in college students in Henan, China. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2023;21.

6. Agency KDCaP. The results of Korean National Health & Nutrition Examinaction Survey2020.

7. Agency KDCaP. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2016.

8. Song T-M, Lee J-Y, An J-Y. Changes in smoking practices and the process of nicotine dependence. Korean Journal of Health Education and Promotion. 2010;27(4):123-9.

9. Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE, Bondy SJ, Selby P, Philipneri A, et al. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ open. 2016;6(6):e011045.

10. Partos TR, Borland R, Yong H-H, Hyland A, Cummings KM. The quitting rollercoaster: how recent quitting history affects future cessation outcomes (data from the International Tobacco Control 4-country cohort study). Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(9):1578-87.

11. Lee ES, Seo HG. The factors associated with successful smoking cessation in Korea. Journal of the Korean Academy of Family Medicine. 2007;28(1):39-44.

12. Kim J. Association between working conditions and smoking status among Korean employees. Korean Journal of Occupational Health Nursing. 2015;24(3):204-13.

13. Kang Y-S, Jang J-S, Hwang Y-S, Hong D-Y, Kim J-R. Predictors of smoking cessation in outpatients. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2003;36(3):248-54.

14. Mi Y. The study of changing smoking status and related factors before and after joining military service. Master's Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul. 2016.

15. Kaczynski AT, Manske SR, Mannell RC, Grewal K. Smoking and physical activity: a systematic review. American journal of health behavior. 2008;32(1):93-110.

16. Kwon E, Nah E-H. Factors Related to Smoking Relapse among Military Personnel in Korea: Data from Smoking Cessation Clinics, 2015-2017. Korean Journal of Health Promotion. 2018;18(3):138-46.

17. Haasova M, Warren FC, Ussher M, Janse Van Rensburg K, Faulkner G, Cropley M, et al. The acute effects of physical activity on cigarette cravings: systematic review and meta‐analysis with individual participant data. Addiction. 2013;108(1):26-37.

18. Service NHI. Health Insurance Expenditure Due to Smoking and Drinking. 2022.

19. Xie J, Zhong R, Zhu L, Chang X, Chen J, Wang W, et al. Smoking cessation rate and factors affecting the success of quitting in a smoking cessation clinic using telephone follow-up. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2021;19.

Date: 08/29/2024