Article: Scotland Kemper, Cayla Grace Sullivan-Land, Sarah Kreider, Deonte Jefferson

From Army Strong to Oorah: A Literature Review Characterizing General Military Culture and Subculture

Introduction

The military is an organization, cultural group, and social group distinct from other organizations, cultural groups, and social groups found within the United States.1 In addition to this already distinctive military culture, military subcultures, and subgroups based on duty status, gender, and/or military occupational specialty/code/rate exist with vastly different normative perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and practices.2 Due to the prevalence and variation of military culture and subculture, research regarding military demographics needs to determine the associations of cultural, social, and biological demographic data when working with military populations.1

Military-generated culture and subsequent subcultures may influence or even cause specific occupational and behavioral variables that contribute to medical condition acquisition and incidence and specific mental and sexual health concerns. To improve the understanding of these diseases’ burdens that active-duty-service members experience, research should focus on characterizing branch-specific cultural practices and prevailing attitudes regarding personality, attitudes, sexual practices, identity, substance usage, and mental health.3,4 Military subculture characterization regarding these factors will lead to improved program development and implementation, leading to an overall alleviation of the disease burdens that active-duty members experience.

Methods

An exploratory literature review was completed to identify and define military subculture, its fundamental components, and its potential impacts on the physical and mental health of service members.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria included publication dates (1995-present) to ensure relevance and currency of information; study design including peer-reviewed empirical research articles, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and theoretical papers; studies focusing on one of the above key terms within populations of Active-Duty Service Members and studies reporting outcomes relevant to characterizing the above key terms. Exclusion criteria included publication types of dissertations, conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries, letters, and book reviews; publication status of preprints and unpublished manuscripts to ensure peer-reviewed quality; study designs of non-peer-reviewed sources and studies involving non-active-duty service members. Other inclusion criteria included military culture, military subculture, United States military, military operation tempo, military recruitment, identity, military theater of service, military occupational specialty/code/rate, gender, masculinity, roles, and stress defined as follows:

- Military Culture/Subculture: the collection of customs, beliefs about relationships and roles, social behavior, institutions, habits, and laws governing active-duty service members.

- United States Military: the United States Armed Forces made up of the six branches the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Airforce, and Space Force.

- Military Operational Tempo: The rate of military actions and missions to train and maintain operational readiness for deployments, garrison duties, and deployments.

- Military Recruitment: The process of attracting and selecting individuals to join the United States Armed Forces for training and employment.

- Identity: Individual active-duty service member’s sense of belonging and self-conception within the context of their respective United States Armed Forces.

- Military Theater of Service: The land, sea, and temporal period where military operations took, are taking, or are planned to take place.

- Military Occupational Specialty/Military Occupational Code/Rate: The service member’s job or role including their training and certifications in the Army and Marine Corps, the Air Force, and the Navy and Coast Guard.

- Gender: The socially constructed norms, behaviors, and roles associated with maleness and femaleness.

- Masculinity: The displayed attitudes and behaviors signifying and validating maleness.

- Roles: The behaviors and responsibilities expected of an individual occupying a given position or status.

- Stress: The mental or emotional response to internal/external stimuli representing a perceived threat or challenge to an individual resulting in nervousness, anger, frustration, sadness, or despair.

Information Sources

The research team worked together to create a search strategy. The devised base search strategy utilized the key terms “military culture,” “military subculture,” “US military,” “US military demographics,” “military operational tempo,” “military recruitment,” “military” and “identity,” “military theater of service,” “military” and “occupational specialty,” “military” and “gender,” “military” and “masculinity,” “military” and “roles,” and “military” and “stress.” The databases listed in Appendix A were then searched with the key terms.

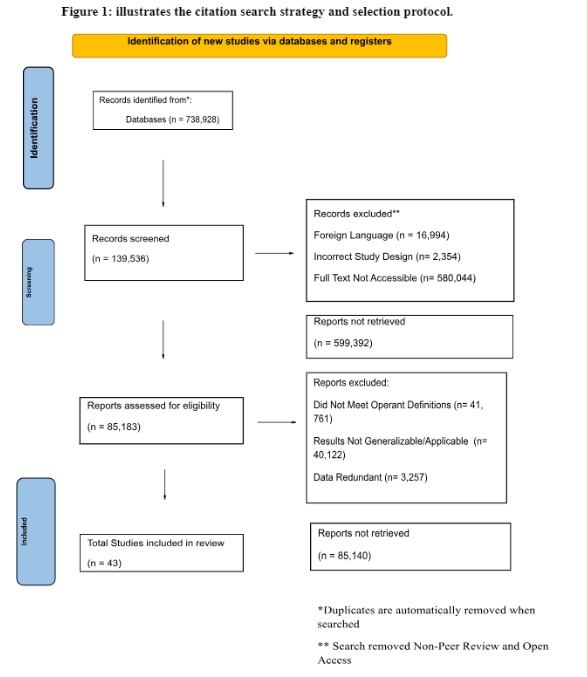

The search was conducted in September 2024 and the base search was modified to each database. The initial query with all key phrases returned a total of 738,928 citations. All inaccessible full-texts, incorrect study design, non-English language, and duplicates were excluded. The remaining 85,145 citations were then screened via review of titles, abstracts by individual team members to determine which articles to pursue for further consideration. The team members, as detailed in the search strategy section, screened the citations for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discussion occurred between the first and second author until all articles to be included were reconciled, determining 43 articles for inclusion into the review.

Search Strategy

The research question for the exploratory review was “What is military subculture and how could it impact health outcomes of active-duty service members?” Data collection based on this question focused on availability and content of articles on military culture, its foundational components, and these factors’ potential impact on health outcomes for active-duty service members.

Given the ample number of articles returned by the query including military as part of the search key-terms, citations were further refined using operational definitions aligned with the research question. Considerations included whether study results were applicable or generalizable to the active-duty military population, the exclusion of meta-analysis articles, and whether study outcomes indicated a similar overall result. Boolean operators and keywords were systematically matched and applied to identify all citations with potential relevance to the research topic.

Critical Appraisal of the Evidence

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Appraisal Tools were employed to evaluate the risk of bias and ascertain the quality of research articles, categorizing them into high, moderate, or minimal risk bias groups. By using the JBI checklists to classify the articles according to their type and evidence strength, they were systematically stratified into the respective risk bias categories. Through the application of the suitable critical appraisal tool for each article type, all 43 articles were ultimately deemed to be of good quality with minimal risk of bias.

Results

Demographics of Active-Duty Servicemembers

To understand military subculture, demographic composition and trends of the population engaging and forming the culture must be characterized. Compared to civilians in the workforce, military personnel are often younger. The active-duty population is skewed to under 40 years of age, with two-thirds of the population being between 18 and 30 of age, which is in part caused by the accessibility of retirement benefits after 20 years of service.5

There are significant gender differences between civilian and active-duty military populations. Women comprise 14.5% of the active-duty force and 18% of the Guard and Reserve populations, whereas women comprise 47.5% of the civilian labor force. The larger percentage of females in the Guard and Reserve may be due to the belief that Guard and Reserve service better facilitates familial responsibilities and roles.6

Membership across the active duty, guard and reserve, and civilian populations is also dynamic, seen by the Guard and Reserve population having a considerable proportion of former active-duty members. Reservists and Guard members can also be called upon during wartime to serve as active-duty service members, further blurring the delineation between them and the active-duty population.6 There are also considerable gaps within the literature concerning the effects of military service upon Guard and Reserve populations, as until recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, where military reliance on these populations to supplement the active force dramatically increased, it was rare for these populations to experience extended durations of active service. The lack of Guard and Reserve operational utilization largely explains that lack of research characterizes the military community and the effects of active-duty service; however, this population must be included within future research.

The racial and ethnic composition of the military also differs from the civilian population. African Americans have a larger presence in both the active duty and Guard and Reserve populations than the civilian labor force, as they are more likely to select military service than their Caucasian peers due to the military’s perceived meritocratic structure. This structure results in increased inclusion of this population as it is believed to offer African Americans increased opportunity compared to academia or the civilian workforce.7 The percentage of individuals identifying as Hispanic rose from less than 4% in the 1970s to 11.2% in 2011; however, they are underrepresented compared to the total civilian Hispanic population, which may be due to military requirements for documented immigration status and education. When reviewing, only the military-eligible Hispanic population has greater representation within the military than in the general civilian population.8

The military population, on average, has higher academic attainment than its demographically matched civilian counterparts. Military requirements designate educational attainment as a necessity of recruitment, resulting in a minute percentage of both active duty populations (0.4%) and Guard/Reservists populations (2.4%) lacking a high school diploma or GED compared to the civilian labor force (10.7%).9 The minimum requirement of a bachelor’s degree for officers and high school for enlisted personnel allows for few exceptions, with less than 5% of enlisted personnel having a GED rather than the attainment of a high school diploma, and further facilitates the educational attainment of the American military population.10

Active-duty service members are more likely to be married and have children at home, though the average number of children among active duty, guard, reserve, and civilians is identical at 2.0 children at home; however, the consistency of the number of children across these groups indicates that active-duty service members form families at a younger age. Activeduty service members are less likely to be divorced than their civilian counterparts overall; however, there are pervasive gender differences.6

Race and ethnicity factor into the familial context of the American military population. African Americans of both sexes and white military men are far less likely to divorce than their civilian demographic-matched peers, whereas white female active-duty service members are more likely to divorce than their civilian counterparts due to conservative beliefs and traditional gender roles.6

Other racial differences contribute to the structure and demographic composition of the American military. Military women have fewer preterm births and less racial inequality in preterm births than their peer-matched civilian counterparts.11 African American military women are also the most likely to have children, with 47.3% active duty of black women having children, compared with 30.4% of white women and 37.4% of Hispanic women, which may be due to female African American active-duty-service-members’ increased duration of military service compared to their white counterparts.5

Military Identity and Subcultural Beliefs Formation and Characterization

Recruitment and Early Career

Though diverse subculture exists within the overall U.S. military culture, the U.S. military can be generally characterized as an environment that conditions certain behaviors by awarding capital to individuals who perform a unique brand of hegemonic masculinity modified to facilitate the institutional goal of successful warfare; however, though the military environment strictly influences engagement in practices like mental health help, individuals bring with them habitus conditioned through developmental socialization within general American society to gender, class, and race/ethnicity.12

The military’s Basic Training, Officer Candidacy School, and Officer Development schools facilitate indoctrination into military culture, integration of moral norms constituting the fabric of military society, and military identity formation that either reinforces or alters the habitus individuals bring to training. Hodges conducted interviews with Marine Corps drill instructors and veterans to evaluate U.S. Marine Corps Basic Training as a form of civic and identified five foundational themes throughout his analysis.13 The importance of teamwork was the first foundational theme incorporated into Marine Basic Training. In addition, Marine Corps recruits are instilled with an emphasis on the value of loyalty. The third theme that emerged was the focus on leadership development, planning skills, and time management, highlighted as subsets of overall leadership skills.

Communication skills were identified as a separate thematic element from leadership, and creative problem-solving in the presence of environmental stressors was the final core theme within the civic framework of integration into military culture and inculcation of military values through Marine Corps Basic Training.13 The results of this study indicate that indoctrination into military culture begins at the very start of active-duty-service-members integration into this subgroup and that identifying the thematic values highlighted by basic training may be a viable avenue for identification of pervasive military belief systems, social mores, and values.

Within the reception and response of the initial role as enlisted or officer, gender-based discrepancies begin to emerge. The Moore et al. study of career beliefs and response to the mentorship of United States Navy Academy students,who undergo a selective process and career mentorship to serve as officers within the United States Navy, identified several key gendered differences between male and female midshipmen.14 Midshipmen were found to have, on average, an intention of thirteen years of military service, with men intending to serve longer than women. The institution of marriage was heavily reinforced within this officer-select demographic, with 93% of respondents planning to marry and doing so before turning 27 years old, with no significant difference between men and women.14 This intention to marry is likely supported by the All-Volunteer-Force’s increasing support for families with programs like full family health coverage, family housing, accredited daycare on base, numerous programs, and activity centers for children.6

There are also financial benefits for marriage with both enlisted and officer service members, as marriage and parenthood result in higher off-base housing and moving allowances.15 The operational tempo of rapidly changing duty status, with service members typically changing duty station every two to three years, also serves as a forcing function to facilitate the decision to marry as orders resulting in the change of duty station orders force couples to decide whether they retain their relationship long-distance, end their relationship, or marry.

The divorce trends of active-duty service members and veterans show the cultural and policy support for marriage the military environment facilitates. While actively in the military cultural environment, couples are less likely to divorce than their civilian counterparts; however, upon exiting the supportive military context, veterans are three times as likely to be divorced as their civilian peers.16 This casual pattern is facilitated by the military environment’s shielding of military families from the stressors, often resulting in divorce, indicating that veterans’ marriages are less stable upon exiting the marriage-positive military context.17

Military Role Performance

Military subculture and its subsequent attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs are facilitated by the performance of roles, either an active-duty service member, a Guard member, a reservist, or a military dependent. Bowen and Martin proposed and tested The Resiliency Model of Role Performance within military populations comprised of active-duty service members, veterans, and military dependents to determine why these individuals’ abilities vary to perform military cultural roles and responsibilities successfully.18 The model contains a system of four thematic and interrelated factors that influence the performance of roles within the military context, including social connections, individual assets, self-orientations, and behavioral health. The model demonstrates the association between resiliency and successful role performance. Social connections, composed of formal and informal social networks and individual assets, have a direct positive and reciprocal relationship that serves as the primary moderator of successful military role performance.19

Social connections (formal/informal social networks) and individual assets have a direct, positive, and reciprocal relationship and are depicted as the primary leverage points associated with influencing role performance.20 These factors also mediate role performance by promoting self-orientation and behavioral health. They may also serve as buffering moderators of the negative impacts of stressors and risks associated with role performance through direct and indirect influences on self-orientation and behavioral health.20

The influence of intrinsic factors, including but not limited to genetics, such as intelligence, personality, temperament, and physical characteristics, do influence resiliency outcomes; however, these factors are treated as fixed or relatively fixed traits of individuals and treated within the model as exogenous factors.21 Individual assets, self-orientations, and behavioral health, differ from social connections, as these attributes are not as greatly influenced by external factors and have more significant potential as targets of interventions and evaluation.18

Formal support systems facilitate socialization, support, and social control within military institutions, and the functional chain of command synergistically interacts with informal interpersonal connections to form normative performances and expectations for military life and culture.22 Military institutions promote social care by planning and implementing intervention and prevention services to members of the military cultural fabric guided by unit leaders’ promotion of connections of professional and personal relationships and direct delivery of military resources. Unit leaders encourage social care by facilitating social cohesion and aiding service members and dependents' management of professional and personal role duties and responsibilities, the effectiveness of which is dependent on the formation of and engagement in the general military and unit communities.22

Informal support systems are organizations or relationships outside the formal military institutional structure of the chain of command. They include group associations, including unit-based support groups, and less structured social networks of voluntary intimate and non-intimate ties maintained by service members and military dependents. These networks have marital, romantic, familial, and platonic relationships with significant others. They are maintained through dynamic exchanges and reciprocal responsibilities in the form of trust, commitments and obligations, positive regard and mutual respect, and norms of shared responsibility and social control.23 These network members promote social care through social capital, which can be defined as social interactions where information and information exchange synergistically function with facilitated linkage to community programs and support.24

Social capital functions through strong and weak interpersonal relationships with intimate and non-intimate individuals, as well as individual service members or military dependents. These ties with diverse individuals facilitate bonding and bridging opportunities, increasing the person’s social capital and engaging in these opportunities.25 Informal networks often are a more pertinent factor in facilitating daily quality of life for service members and military dependents than formal networks, as these networks serve as the primary level of social care.26 These primary levels of influence also contribute to the five dimensions of individual assets, which mediate role performance.

Bowen and Martin identified physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual domains as the primary dimensions comprising individual assets’ totality.18 The Army’s Comprehensive Fitness initiative and the current Air Force’s Comprehensive Airman Fitness initiative also identify these domains as areas of intervention to improve operational readiness and individual capacity, and there is an existing literature basis for the theoretical and empirical validity of these dimension-rooted in the field of positive psychology.27

These individual assets constitute attitudinal and behavioral strength dispositions to successful life and conflict navigation, modified through formal and informal intervention and prevention activities. Formal and informal interventional activities should focus on strengthening an individual’s opportunity structure, political influence, socioeconomic standing, and social connections to improve these assets through influencing an individual’s orientation to self (e.g., self-esteem, self-efficacy, locus of control, sense of coherence, hardiness) and one’s behavioral health (emotional well-being) as central mediators between formal and informal support systems and individual assets on the left side and role performance on the right.18 The characterization of these factors is essential for the continuing development of the model within the target population. This characterization will allow for a focal point of evaluation to determine the quantitative association between the informal and formal network structures comprising military subculture and the successful performance of normative and divergent military roles.

The Characterizations and Contributions of Military Branch, Status as Enlisted or Officer, Military Occupational Specialty/Code/Rate, and Theater of Service

Though there is an overarching military subculture, diverse subcultures exist based on the branch of military service, status (enlisted or officer), MOS, and theater of service. This diversity leads to the variance of outcomes for members of the population. These factors directly contribute to individual service members, veterans, and attached dependents’ identity, beliefs, increased risk of specific disease burdens and adverse outcomes, perception of illness and treatment, perception of medical providers, and attitudes toward mental health.2

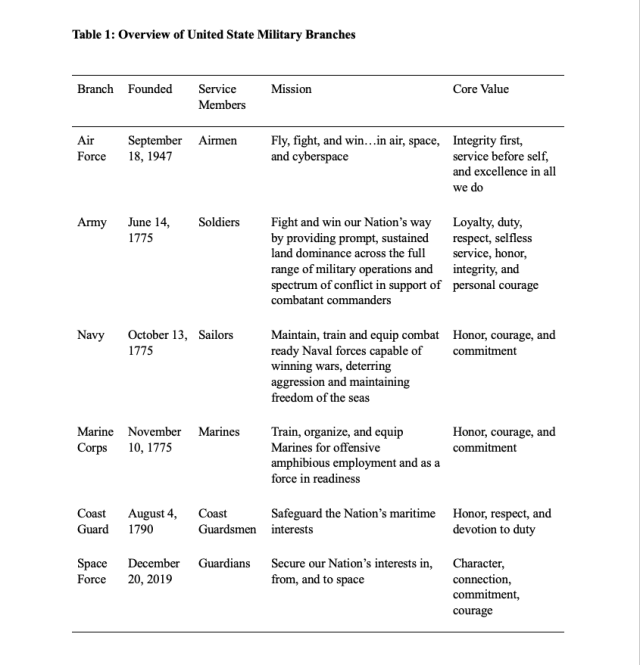

The difference between military branches results from differences in institutional mission statements, subsequent operational activities, and corresponding values. Table 1 provides an overview to help visualize these differences between military branch foundations, service members, mission, and core values.

These differences have led to institutional differences in service intensity and associated burdens. During the modern Iraq and Afghanistan Theaters, the Army experienced the greatest deployment burden of all service branches. The Army carried nearly 52 percent of troop deployments while only constituting 39 percent of the active-duty force in 2009; comparatively, the Air Force, while comprising 23 percent of the active-duty force, carried only 15 percent of troop deployments. The Naval deployment cycle and burden, compared to other branches in both times of peace and war, have a dynamic operational tempo, with sailors spending cyclic durations of six months at sea and then six on land.6 With these factors in perspective, it becomes unsurprising that military dependents also experience corresponding burdens, with Army and Marine Corps spouses experiencing the highest weighted rates of depression.28

Alcohol abuse and usage as a maladaptive coping mechanism for service members is also pervasive in general military culture moderated by military separation and branch of service.29 Porter et al. significantly associated heavy weekly drinking with military separation among female service members but not their male counterparts.30 Service member and spouse binge drinking were found to interact in that a single partner’s reported binge drinking resulted in a decreased risk of military separation. In contrast, dual binge drinking was significantly and positively associated with increased military separation. The service branch was also identified as a moderating variable, with Marines experiencing the greatest odds of separation, followed by the Army and Air Force and Navy/Coast Guard having lower military separation odds. Service member PTSD and depression, spouse anxiety, and gender identity as a female service member were also identified as moderators, increasing military separation risk compared to male service members.31

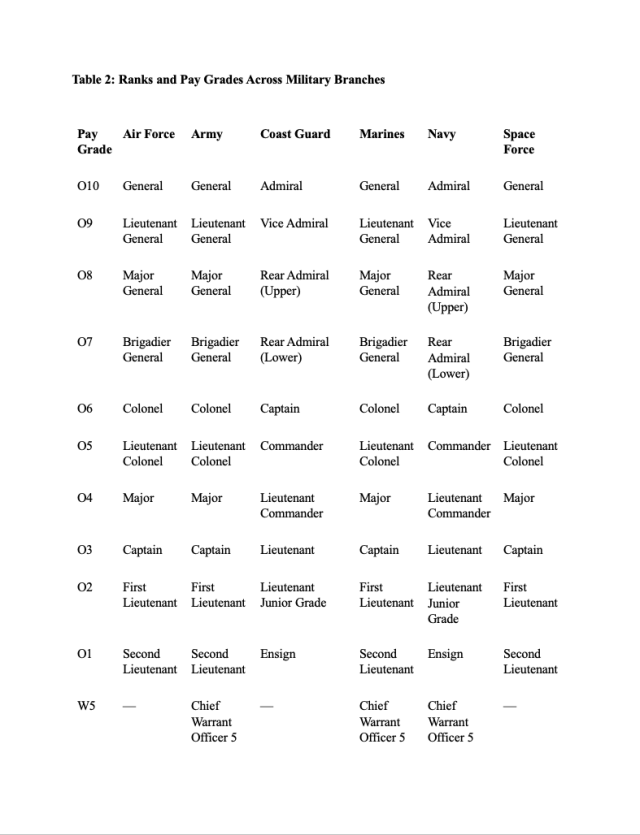

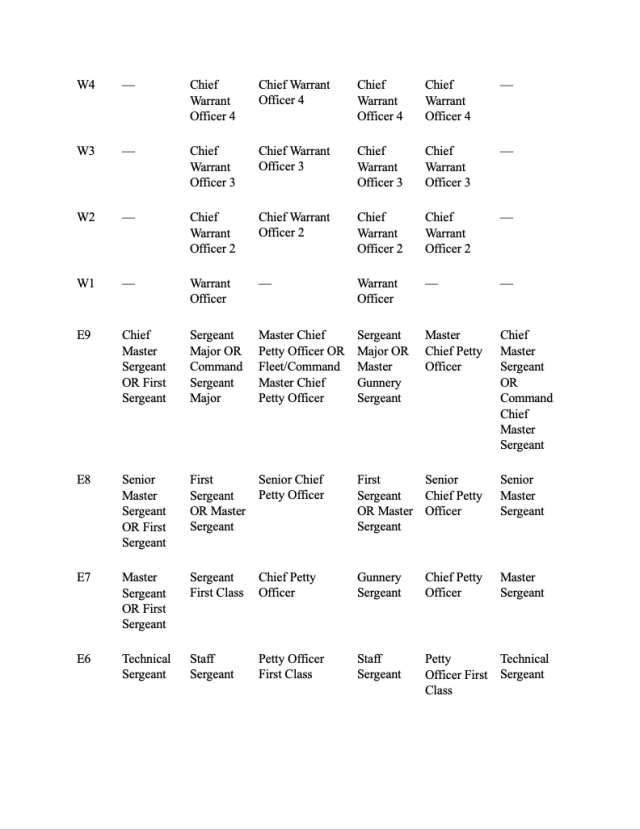

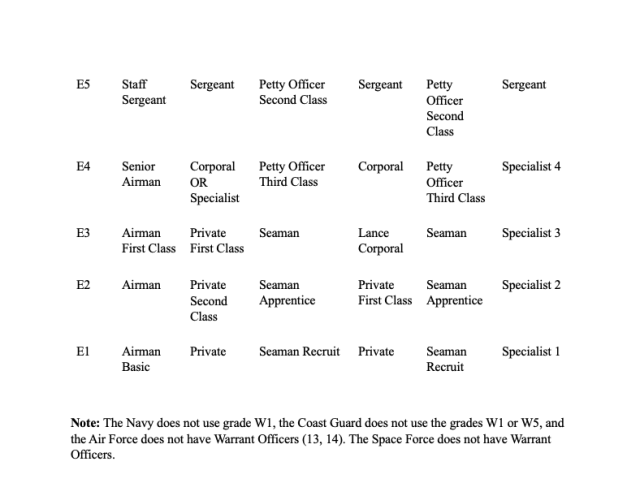

In addition, military status (enlisted or officer) moderates military identity, roles, responsibilities, and activities heavily. The hierarchical chain of command facilitated by these statuses is illustrated in Table 2.

This helps to contextualize Held’s et al. study of harm endorsement and perpetration by branch and rank. A total of 22.4% (n = 51) of participating veterans and active duty service members endorsed having caused harm on deployments, while the remaining individuals (76.6%; n = 177) either denied or did not specify having caused harm on deployment.31Soldiers and Marines serving in post-9/11 combat theaters were also more likely to have done harm, with E4-E9, officers, and then E1-E3 doing the most harm, respectively.

Additionally, veterans and service members reporting harm perpetration while on deployment are more likely to be exposed to other common combat exposures, such as being significantly more likely to experience “fire or explosions," “dangerous chemicals or radioactivity," “assault with a weapon," “danger of death or injury during military service," “severe injury during military service," “witnessing death or serious injury," “seeing or handling dead bodies,” and “witnessing severe human suffering.”31 The endorsement of causing harm on deployment and increased exposure to traumatic combat experiences suggests that the act of causing harm, injury, or death may be yet another of the traumatic experiences that deployed service members commonly experience during their service while deployed.

Discussion

The synergistic influence of behavioral, demographic, and occupational factors provides insight into why the military population comprised of active-duty service members, Guard members, reservists, veterans, and their dependents experience a more significant risk for the development and progression of conditions, specifically regarding their mental and sexual health when compared with their demographically matched civilian population. However, this topic is under-characterized and must be subjected to an ongoing inquiry. Another probable mediator of this diverse population’s acquisition, progression, treatment, and long-term outcomes of these conditions may be the specific occupational and behavioral patterns caused or influenced by the associated military cultures and subcultures.

The military population generating the general military culture and corresponding subculture is predominately male, with an overrepresentation of minority ethnicity and racial demographics due to the perception of increased opportunity within the contrived meritocracy of military institutions. The individuals entering service tend to hold more conservative values regarding familial responsibilities, gender roles, and gender identity than the general civilian American populace. Traditional conservative beliefs regarding identity, gender, and family combined with family-focused institutional policy lead to the heavy reinforcement of institutional marriage and a specific culturally and organizationally reinforced form of military hegemonic masculinity based on strict masculine role performance.

Theoretical models, like the Resiliency Model of Role Performance, that have been operationalized within the socio-cultural and environmental context of the military provide a means to characterize, contextualize, and potentially quantify the effects of exposure to military culture and subcultures. They can also evaluate relationships between the performance of roles within the military context and include social connections, individual assets, self-orientations, and behavioral health to improve the health outcomes of all the individuals contributing to the ever-growing body of the military population. As Meyer states:

“As military culture becomes more diverse and care delivery crosses service lines, the challenge of understanding military patients will continue to increase. So, too, must the efforts of military medical education rise to the challenge to ensure that all military patients receive culturally competent care.”2

Conclusion

The demographics of the United States Armed Forces skew to majority male, under the age of 40 years old, and a higher percentage of racial and ethnic minorities compared to the civilian population. Military members are overall more likely to be married than their civilian counterparts, though this varies based on the age group for female service members. Military members also attain higher levels of education than the civilian population. This population of military members generates a culture and subsequent subcultures unique to the military that varies based on branch, status as an enlisted person or officer, MOS, and more. These cultures are prevalent throughout the military, starting with indoctrination at military training schools for all members of the military.

Members of the United States Armed Forces are at a higher risk of acquiring many medical and psychiatric conditions compared to the civilian population. The management of these conditions is also overseen by the United States Armed Forces. The characterization of the demographics of the military population and the characterization of military cultures are important, in part, to help understand why status as a military member leads to this increased incidence and prevalence of conditions. Characterizations of military subcultures and their relationship to the physical and mental health of that subgroup’s members can help identify risk factors that may be mitigated to decrease the acquisition and progression of these conditions.

Further research is needed to determine how knowledge of the general military culture and its subcultures can be implemented in the United States Armed Forces to mitigate the potential negative effects that hegemonic masculinity has on the military’s members individually and the military’s operational effectiveness collectively. Continuing investigations should also be conducted in the different branches, divisions, and groups of the Armed Forces to determine their specific subculture characteristics and traits, how they affect the career, physical, and mental outcomes of their groups, and how these subcultures can be changed to lead to better outcomes in those groups and the military as a whole.

Appendix A: Literature Review Database List

This literature review was conducted utilizing the following databases: Ebsohost, Complete, AgeLine, Agricola, AHFS Consumer Medication Information, Alt HealthWatch, America: History & Life, Anthropology Plus, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycTests, CINAHL with Full Text, Communication & Mass Media Complete, Computer Source, Consumer Health Reference eBook Collection, Criminal Justice Abstracts with Full Text, Current Biography Illustrated (H.W. Wilson), eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EconLit, Education Research Complete, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Environment Complete, ERIC, Family Studies Abstracts, Film & Television Literature Index with Full Text, Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, GeoRef, GeoRef In Process, Global Health, Google Scholar, GreenFILE, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, Health Source - Consumer Edition, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Humanities Source, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (ISTA), Jewish Studies Source, Legal Collection, Legal Information Reference Center, Library Literature & Information Science Index (H.W. Wilson), Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, Literary Reference Center, Literary Reference eBook Collection, MAS Complete, MAS Reference eBook Collection, MasterFILE Complete, MasterFILE Reference eBook Collection, MathSciNet via EBSCOhost, MedicLatina, Middle Search Plus, Middle Search Reference eBook Collection, Military & Government Collection, MLA Directory of Periodicals, MLA International Bibliography, Newspaper Source Plus, One Search, OpenDissertations, Philosopher's Index, Play Index (H.W. Wilson), Political Science Complete, Primary Search, Primary Search Reference eBook Collection, Professional Development Collection, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Public Administration Abstracts, PubMed, Race Relations Abstracts, Referencia

Author List

Scotland Kemper, [email protected], 529 S Parsons Ave Apt 1211, Brandon, Florida 33511

Cayla Grace Sullivan-Land, [email protected], 843 E Stottler Dr. Gilbert, Arizona 85296

Sarah Kreider, [email protected], 9702 Grove Lake Way Apt 206 Knoxville, Tennessee 37922

Deonte Jefferson, [email protected], 320 Bob Bullock Loop Apt 18306, Laredo, Texas 78043

Primary Author Bio:

Scotland Kemper, an Ensign in the U.S. Naval Medical Corps, is pursuing an Osteopathic Medicine degree at Nova Southeastern University and holds an M.P.H. from Baylor University. Raised in a Marine Corps aviation family, she is committed to improving health outcomes for service members by addressing physical and socio-environmental factors.

Date: 10/10/2024