Article: T.Ligthelm,, J.LOUW J.T.Claassen(South Africa)

Long-Distance Mass Body Repatriation from an Ebola-risk area

MASS BODY REPATRIATION

This paper discusses the organisation approach to a mass body repatriation from Nigeria to South Africa during the Ebola outbreak in Nigeria. A complete different approach was followed by flying in refrigeration mass body repatriation trucks and support vehicles by cargo plane to collect the bodies from various mortuaries within the city. These trucks, with the bodies were then driven back into the plane and flown back. During the operation, all precautions for possible Ebola Virus Disease were implemented.

Introduction

A case of Ebola Virus Disease was introduced into Nigeria on 20 July 2014 when an infected Liberian man arrived by aeroplane into Lagos, Africa's most populous city. The man, who died in hospital 5 days later, set off a chain of transmission that infected a total of 19 people, of whom 7 died(1). Nigeria was only declared Ebola-free on 20 October 2014(2).

On Friday, 12 September 2014 at approximately 12:44 local time (3) a guesthouse, located within the Synagogue Church of All Nations (SCOAN) premises in Lagos, Nigeria collapsed. This resulted in the largest number of South African citizens killed in a single event on a single day since World War II. 81 South African citizens and 4 persons travelling with South African travel documents were among the 116 people killed in this event(4). The average age of the deceased was 43, 4 years with 36 males and 48 female (n 84). The 30 unknown bodies were of unidentified nationality and may also have been South African (later proven not to be South African). An undeclared number were injured, amongst them 26 South Africans. The bodies and those injured were trapped together underneath the building rubble for an extended period before all injured and bodies were recovered from the site.

The bodies were evacuated from the site by the Nigerian authorities to three mortuaries spread around Lagos:

- Ikeja Mortuary: 7 Bodies- 5 km from the airport.

- Yaba Mortuary: 63 Bodies- 9 km from the airport.

- Isolo Mortuary: 46 Bodies- 15 km from the airport.

These facilities had a non-reliable and often disrupted electricity supply, with limited body storage space, resulting in bodies in various stages of decomposition, stacked together in non-ideal storage facilities. The standard of storage in these mortuaries varied from poor to very good.

Post mortem examinations were conducted by the Nigerian authorities, with causes of death indicated as shown in Table 1.

| Cause of Death | Number (n 84) |

| Asphyxia | 23 |

| Multiple Injuries | 36 |

| Exsanguinations | 14 |

| Head Injury | 4 |

| Chest Injury | 5 |

| No record available | 2 |

Table 1: Causes of Death

Problem Statement

To repatriate up to 115 bodies in non-ideal condition, possibly contaminated with body fluids from Ebola Virus patients, from a highly populated and congested city, with very limited infrastructure and political turmoil back to South Africa, over a distance of 4500 km.

Discussion

Ebola Risk

Believers from all over Africa travel to this SCOAN church, due to the claims and rituals of alleged healing which are widely publicized (3). Numerous allegations and non-substantiated statements were made at the time that the pastor of this church, T.B. Joshua, had claimed to be able to cure Ebola Virus Disease and able to “wash off Ebola” from people exposed to the disease. As the nationality of the non-South African victims were unknown at the time, it was possible that Ebola patients from Sierra Leone, Guinea or Liberia, where the Ebola outbreak occurred or from Nigeria itself, may have taken a pilgrimage to the church. These allegations, which could neither be substantiated nor proven false, was holding the risk that some of the victims killed in the event, may have been suffering from Ebola Virus Disease. As bodies were transported and stored in close proximity with other bodies from the city where an outbreak occurred, the risk was that the decomposing South African bodies were contaminated with body fluid from Ebola Virus Disease patients. The deceased could also have been suffering from other communicable diseases such as extreme-drug resistant Tuberculosis, as many desperate patients undertook a pilgrimage to the church for healing.

Ebola Virus Disease is caused by a virus from the family Filoviridae. Human-to-human transmission occurs through contact with the body fluid from an infected patient. This transmission is well described, with an incubation period of 21 days (1). However, the duration of the virus’s life cycle in a decomposing body is not well researched, especially in high and humid environmental temperatures and non-ideal storage conditions.

The mortuary infrastructure of Lagos is very limited, with very limited body transport capabilities, limited space in dilapidated mortuary buildings, chaotic travel conditions and an unreliable power grid. This resulted in a challenge to the South African military and civilian health authorities to identify and then repatriate a minimum of 85 decomposing bodies, possibly contaminated with body fluids from Ebola Virus Disease victims, over a distance of nearly 4500 km to South Africa.

Due to the risk involved, the principle decision was taken to manage all bodies as possibly Ebola contaminated and to protect all staff members through high risk bio-safety precautions(5).

Transport challenges

The number of bodies, condition of the bodies and the bio-safety risk ruled out the use of commercial repatriation and a decision was taken to launch a joint military-civilian operation to repatriate the bodies to South Africa.

Although considered, the possibility of cremation was ruled out due to very limited facilities in Lagos and that the practice would not be accepted by the families due to cultural practices in South Africa.

No mass body transport capabilities were available in Lagos. Bodies are normally transported wrapped in a shroud by private undertakers in small sedan vehicles. Limited numbers of these vehicles were available.

Limited space was available at the mortuaries to prepare bodies for repatriation while taking the bio-safety procedures into account.

Due to the limited transport capabilities, deteriorating conditions of the bodies and bio-safety risks, a decision was taken to deploy a fully self-sustained capability team able to receive, prepare, decontaminate, cool, transport and repatriate the bodies back to South Africa in a respectful manner.

Planned Solution

Photo 1: Mass Body Repatriation Truck’s internal outlay

Photo 1: Mass Body Repatriation Truck’s internal outlay

In order to address the unique challenges, a combined civil-military plan was compiled to repatriate up to 115 bodies to South Africa in a combined transport and repatriation operation (the number was unconfirmed at this stage but minimum 85 South Africans was reported missing, assumed dead, with the possibility that more of the unidentified bodies may have been South Africans or citizens of the neighbouring countries).

A Reconnaissance Team was deployed to Lagos from 7-10 October 2014 to assess all facilities, assess the condition of the bodies and obtain principle approval from the Nigerian Authorities. All facilities were visited and all roads travelled at the proposed times, to determine travel times. It was concluded that the full repatriation process will need to be self-sustained with own capabilities and limited local support capabilities.

This reconnaissance resulted in a planned Mass Body Repatriation Operation. Due to bureaucratic challenges, traffic situation, deteriorating condition of the bodies, political turmoil, distance and the number of bodies, it was decided that the best solution will be a massive single day operation to, preferably, repatriate all bodies in one operation.

Due to the nature of the operation, a joint military and civilian operation was planned, combining the command and control, operational planning and decontamination skills of the South African Military Health Service with the forensic pathology skills of the civilian Forensic Pathology Service of the Department of Health. This was supported by specialists from the SA Police Service. Both civilian and military Environmental Health staff were utilised, with military psychologists and medico-legal staff as support elements.

Due to transport challenges in Lagos a plan was compiled to deploy mass body repatriation trucks with cooling capabilities by cargo plane to Lagos. Support vehicles, also transported with the cargo plane, would then aid these trucks. Each support vehicle contained air-conditioned inflatable tents, trestles, personal protective equipment (PPE), decontamination equipment and body bags in order to establish a body preparation station at each mortuary. Teams of civilian and military expert personnel would be deployed to each mortuary consisting of a command element, forensic pathology officers; military emergency care personnel trained in decontamination; environmental health officers; psychologists to initiate debriefing of staff; technical personnel and a medico-legal consultant.

A detailed flow-chart, linked to timelines, was compiled for the entire plan and specific report lines were identified. This assisted in planning the inter-relationships with contractors and suppliers to coordinate actions. Bagging channels were planned and the size of the team and number of channels were planned based on the number of bodies at each mortuary facility.

Special authority was obtained through a Note Verbale to the Nigerian Government to drive South African vehicles in the country. All drivers obtained International Driving Permits prior to the deployment. Authority was obtained to import and export vehicles and equipment through the customs authorities.

Management of valuables and personal possessions of the deceased were planned for.

Command and Control

A military commander with a civilian co-commander was appointed and approved by all staff contributing institutions. These commanders were given mission command flexibility during the operation. Functional control was executed by each specialist grouping, be it military or civilian, over the specialist function answering to the joint command structure. This command affiliation was described in the pre-deployment formal plan and approved by the Director-General of the Department of Health and the Surgeon General.

A command network utilising the local cellular phone network was planned.

Body Identification

A Body Identification Team consisting of identification experts from the South African Police Service and initially also Forensic Pathology and Forensic Dentistry experts were deployed to Lagos. The team envisaged to obtain fingerprints from the deceased for comparison to South Africa’s national fingerprint data bank, obtain dental records for dental identification where fingerprints failed, and to collect DNA samples. Due to Nigerian authorities’ decisions, this team was only allowed to participate partially in identification processes. The local authorities decided to only utilise DNA identification and to outsource the DNA matching function to a private laboratory. (This process delayed the repatriation to a 6-month operation and forced a second wave repatriation operation).

Execution

As soon as the Nigerian authorities agreed to the DNA identification of the majority of bodies a Mass Body Repatriation Capability, with staff, was deployed to Lagos. An Antonov 124 was chartered, transporting 4 Mass Body Repatriation Trucks with a combined capacity to transport 85 bodies and 4 Light Delivery Trucks each with an inflatable air-conditioned tent, generators, flood lights, decontamination and hand-washing facilities, protective clothing and body bags. As water and electricity supplies in Lagos are frequently disrupted, generators were taken along. Water tanks were taken along and filled by a pre-arranged contractor on arrival at Lagos airport. As the standard of diesel was questionable, fuel for the trucks and generators was also taken along.

Photo 2: Forensic Pathology Mass Body Transport Trucks and support vehicles positioned in Cargo Aircraft

Photo 2: Forensic Pathology Mass Body Transport Trucks and support vehicles positioned in Cargo Aircraft

The plane was accompanied by a second Airbus A320 passenger plane with 81 staff members, including:

- Command Element of 13 members including a medico legal consultant;

- 32 Forensic Pathology Officers;

- 16 Military Emergency Care staff trained in decontamination;

- 8 Environmental Health Officers to enforce and supervise decontamination;

- 2 Military Psychologist to manage continuous debriefing of staff; and

- 2 Technical staff to sustain vehicles and generators.

A Chaplain accompanied the team for religious observance, as well as representatives from the Department of International Relations and Cooperation. A South African Police Service team to manage personal possessions and valuables were deployed in advance.

The team arrived on 14 November 2014 at 01:30 Nigerian time after a flight of 6 hours at the Military Section of Lagos International Airport. Following custom procedures, the team was issued with their PPE equipment. Sizes of PPE were already determined in South Africa during one of the briefing sessions, which made it easy to distribute PPE correctly in terms of size. Snack packs and bottled water were also issued before departure to the mortuary facilities. The team divided into three teams each consisting of mass body repatriation trucks and a support vehicle. Staff transport was arranged by the South African Consulate in Lagos. Each convoy was escorted by a military security element from the Nigerian Defence Force, coordinated by the South African Military Attaché. It took 2 hours to off-load vehicles and equipment, which included refuelling of the vehicles with diesel and distribution of PPE and equipment. The internal 50 litre water tanks of the disaster vehicles were also filled by the contractor for use at the mortuary facilities. The convoys departed from the airport at 04:20 Nigerian time and arrived at the mortuaries at 05:34. Each of the three teams’ disaster vehicle drivers received a personal satellite-tracking device through which the movements and locations of the teams could be monitored from within Nigeria and South Africa by command structures. To the benefit of the repatriation team, the 7 bodies at Ikeja mortuary were transferred the day before to Yaba mortuary and the team members allocated to Ikeja mortuary could be moved to Yaba where the majority of bodies (63) were located to increase the manpower and capacity.

According to the flow-chart plan, reporting took place at specific pre-determined reporting timelines to ensure coordination.

At each mortuary a Preparation Station was set up and these tents were cooled down with mobile air-condition units and generators to an average temperature of 22°C. The tents had an entrance that was positioned in proximity to the exit of the mortuary and an exit where the mass body repatriation truck was positioned. The trucks were pre-cooled en route to the mortuaries and maintained an average temperature of 10°C for the full day. After all of the bodies were successfully transferred to the truck and the load box doors closed, the temperatures dropped to 2.5˚C.

Photo 3: Body Preparation Station at one of the Mortuaries

Photo 3: Body Preparation Station at one of the Mortuaries

All Preparation Stations were set-up in a three-area designated concept(5):

- Green rest area for staff;

- Yellow decontamination area; and

- Red high risk area where the bodies were managed.

Although by the time the repatriation was completed (63 days after the incident), the risk for Ebola and other communicable diseases had ceased due to the time-lapse since death, the condition of the bodies remained an area for concern. Therefore, the decision was taken to maintain the planned approach of full protection against Ebola to test the system and to protect staff against all possible risks. All staff therefore wore full protective equipment (PPE) which was donned and doffed under direct supervision from the Environmental Health Officer:

- All staff changed from standard uniform to theatre scrubs and waterproofed boots. This attire was worn throughout in the green area.

- When entering the yellow area, staff donned a second layer of protective equipment consisting of a water repellent (but breathable) paper cover-all with cap, a N-95 respirator mask and first pair of cuffed gloves, with cuffs worn under the sleeves of the coverall.

- Before entering the red area they doffed a third layer of protective clothing consisting of a water repellent long sleeve gown, second pair of gloves and a full face visor. When advanced decomposing bodies were transferred, red aprons were used which was ripped-off immediately and replaced when contaminated.

Goggles were found not suitable due to high humidity and ambient temperature in Lagos. Gas masks with filters were taken along for offensive odours from decomposed bodies, but staff preferred not to wear it due to heat and humidity.

At each mortuary, the identified bodies were pointed out to the team by the Nigerian staff and identification detail was confirmed by the SA Police Service. Identification tags were attached to each body. Traumatic amputated body parts were placed with the body in the same bag and identified.

The body was then manually moved in a mortuary tray to the tented body preparation station. The body was manually transferred to a prepared mortuary tray with a pre-positioned body bag (all bodies were naked due to post mortem investigations conducted by the Nigerian authorities). Bodies were then:-

- Bagged in a transparent body bag and sealed.

- This bag was decontaminated by spraying the bag with a chlorine solution (4000 ppm) and then wiping it down all around.

- The bag was then placed in a second white bag and 15 ml formaldehyde solution was squirted between the layers of bags. This second bag was then also sealed. The vaporising formaldehyde created a formaldehyde gas-layer between the bags.

- The sealed second bag was similarly decontaminated using a chlorine solution and placed inside a third opaque metal lined body bag.

- Formaldehyde was again squirted between the layers and the outer bag sealed.

- The outer bag was decontaminated again using a chlorine solution.

- The outer body bag was then identified, using a waterproof tag. This identification was double-checked. A colour code system was used for all identification tags (bodies and body bags) to indicate Provincial destinations within South Africa.

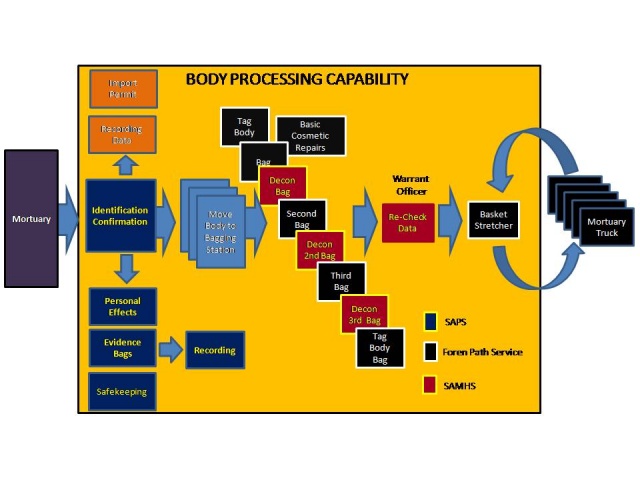

Fig 1: Outlay of the Body Preparation Station

Fig 1: Outlay of the Body Preparation Station

On completion of this preparation process the bagged body was placed in a Stokes basket stretcher and moved to the pre-cooled mass body repatriation truck. These basket stretchers fitted into numbered racks in the truck. To assist with recordkeeping, the names and body numbers of bodies were also recorded on the white board within each truck. On average it took 15 minutes to prepare a body for repatriation.

Photo 4: Sealed and decontaminated body-bag moved into Transport Truck

Photo 4: Sealed and decontaminated body-bag moved into Transport Truck

Anecdotal, it was confirmed that no unpleasant odours from the decomposed bodies were detected after the triple sealing process. Protection from formaldehyde vapours was achieved by utilising N-95 respirator masks and airflow in the tents from the air conditioning.

Staff rotated every 40-60 minutes. Due to PPE and ambient temperature staff was forced to rotate within 60 minutes from donning red area protective clothing.

Staff decontaminated at each rotation through a structured supervised process; removing the first layer of PPE at the exit of the red-area and washing their hands over inner gloves, walking through a foot-bath to the yellow area where they removed the second layer of PPE and decontaminated hands again. They then remained in the green area for 80-120 minutes where they were instructed and supervised to re-hydrate before dressing up to enter the red area again(5). A psychologist was positioned in the green area throughout to debrief staff informally and establish rapport with staff for formal debriefing at a later stage. Although clinical temperature monitoring equipment was taken along to monitor staff’s body temperature, it was not utilised due to the effective cooling of the tents by the air-conditioners.

Snack packs with cool drinks and water were issued to all staff on arrival in Nigeria and meals were delivered at the Green Area by the South African Consulate.

Only 74 bodies were released by the Nigerian authorities, due to their insistence on DNS identification as a sole identification method.

On completion of the preparation and loading process, all teams and equipment were decontaminated. All support vehicles were loaded and mass body repatriation trucks, support vehicles and staff transport returned to the military airport.

All personal possessions and valuables of the deceased were collected and recorded by a team of the SA Police Service. Lockable containers for the purpose of safekeeping of valuables were taken along.

By 20:00 local time, all teams reassembled back at the airport (total deployment 14, 5 hours) and after a memorial service, the trucks and support vehicles were ready to be re-loaded. It was not possible to connect the trucks in flight to the aircraft power system, as it was a chartered aircraft arriving in South Africa the day before the operation. The trucks therefore had to be cooled at maximum on the ground and temperatures reached 2˚C. Unfortunately the Nigerian authorities insisted the trucks be re-opened at the last moment and executed a time-consuming inspection prior to departure, resulting in the loss of 4°C of cooling. Optimum re-cooling was then achieved in the short period prior to loading the vehicles.

An Import Permit for all bodies was generated and forwarded to South Africa, adhering to Port Health requirements in terms of the International Health Regulations.

The vehicles maintained an acceptable temperature during the 7-hour flight and arrived in South Africa at 12˚C. The vehicles were then driven off the plane, connected to three-phase electrical power inside a hangar and immediately re-cooled reaching optimum 2°C within 2 hours.

A ceremonial memorial service was conducted on arrival in South Africa, followed by the distribution of bodies, according to the colour coding, to regional mortuaries. All bodies arrived at the destinations within 48-hours after arrival in South Africa.

On completion of the final DNA identification process of the remaining 11 bodies, a second repatriation operation was executed using a C-130 military plane and a container mortuary on 5 February 2015. Due to the limited number of bodies, local Nigerian transport was utilised to take teams to a single mortuary and to transport prepared bodies to the containerised mortuary on board the plane. The same bagging procedure as in Phase 1 of the operation was implemented. The mortuary was continuously cooled using a generator positioned outside the C-130 until take-off and maintained the temperature during the flight. During the hour-longstop for refuelling at Kinshasa, the generator was reconnected to re-cool the mortuary. Upon arrival at Waterkloof Air Force Base, the 11 bodies were immediately transferred to a mass body repatriation truck previously used.

The standard 5-step military debriefing process of wash, a meal, rest, a memorial service and then debriefing was planned for staff exposed to the decomposed bodies. Although showering in Lagos for all staff prior to the return flight was planned, it could not take place due to a water supply failure at the air force base. A full meal was served to all staff members on arrival in South Africa and all personnel participated in the memorial service. Personnel then attended formal debriefing sessions. Although the bodies were seriously decomposed and the conditions were unpleasant, no acute post-traumatic stress reactions have been reported to date.

Feedback from staff indicated that they felt safe and protected within the three-area system with three layers of PPE and the controlled decontamination.

In the initial Ebola risk planning a decision was taken not to allow the opening of the inner transparent bags and not to allow night vigils with the bodies. A procedure was compiled to only open the outer opaque bag in a controlled environment and allow viewing through the transparent inner bags if families insist. A directive to this regard was issued by the Director General of Health to undertakers collecting bodies for burial. Due to the time delay, the Ebola risk however ceased, but families were still discouraged to view the remains due to the appearance and subsequent emotional trauma. Only one family insisted to opening the bags.

Lessons Learned and Conclusions

A mass body repatriation of high-risk bodies over a long distance is a complex operation requiring detailed planning. A detailed task-flow chart coupled with estimated times assist in ensuring a seamless operation.

Self-sufficiency (down to micro-level) remains a critical requirement to ensure execution.

The use of mobile mass body repatriation trucks in a cargo plane is a possible solution, even if no cooling can take place in flight, but on condition that trucks are kept closed and is appropriately isolated, for a period of up to 12 hours.

A three-layer bag system used in a three-area preparation area (green, yellow and red) with three layers of protected clothing is suitable for a high bio-safety risk operation.

The principles used in high security bio-safety isolation can be applied in the handling of high-risk mortal remains.

Cooling areas are essential for non-acclimated personnel who are suddenly expected to execute manual labour in high ambient temperature areas. Enforcing re-hydration is a critical precaution.

Civil-military cooperation is possible in complex operations through proper planning, role-identification and appropriate command and control.

Post-traumatic stress can be prevented/limited by using a planned debriefing process which should include and integrate psychologists with the team and then cleaning, rest and feeding, ceremonial honours and then debriefing. Informal psychologist interaction throughout the operation enhances rapport between staff and psychologist.

Cremation is not a generally cultural acceptable procedure, but triple sealed bodies can be viewed within restrictions to address cultural practices.

Date: 07/13/2015

Source: MCIF 3/15