Article: M.A. ZAMORSKI, D. BOULOS, A. DOWNES (CANADA)

The Impact of the Mission in Afghanistan and Mental Health System Renewal in the Canadian Armed Force

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) deployed many personnel in support of the mission in Afghanistan. Concurrently, the CAF renewed its mental health system to better meet the needs of its personnel. This article summarizes the key findings of a large health services research study that assessed 1) the mental health impact of the mission; 2) the impact of diagnosed disorders on ongoing fitness for duty; and 3) the effects of mental health services renewal on delay to care and on occupational outcomes after treatment.

Introduction

Canada deployed many personnel in support of the complex military operations in Afghanistan over the period 2001–2014: Some 43,000 Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) deployed as part of that conflict, and 158 lost their lives.1 Many more were seriously injured, physically or psychologically, and Canada is trying to understand the costs of this mission, in both human and economic terms. There has been growing awareness of the central role that service-related PTSD and other trauma-related disorders play in those costs, both during and long after the conflicts end.

Early in the mission, and especially as the intensity of the combat operations increased, the CAF took measures to address the mental health impact. Psychiatrists were added to the deployed MH teams,2 mental health screening was reinforced (especially postdeployment), and a third-location decompression (TLD) program was initiated to help personnel returning from combat zones transition more smoothly.3 Other key re inforcements in the CAF mental health system since the beginning of the Afghanistan mission include 1) doubling the number of mental health clinicians; 2) adding two regional

centres for treatment of the psychiatric consequences of operational trauma, bring the total to seven; 3) initiation of systematic mental health and resilience training across the career and deployment cycle; 4) development (in partnership with Veterans Affairs Canada) of an innovative peer support program; and 5) reinforcement of the CAF’s mental health surveillance and research capacity.4 The ultimate intent of these efforts was to decrease the incidence of mental disorders, decrease psychological distress, shorten delays to care, improve the quality of care for those with trauma-related disorders, and optimize the rehabilitation of those with mental disorders.4 This article summarizes the results the CAF’s Operational Stress Injury and Outcomes Study, a major health services research project undertaken by the CAF. It is part of a larger effort in Canada5 and elsewhere to understand the impact of the recent conflicts on the mental health of the personnel who deployed in support of the mission, the impact of those mental health problems on the military employer, and the effectiveness of military mental health system renewal. The key findings of the study are described, along with points of reference from other major population health studies in Canada and elsewhere.

The Operational Stress Injury Incidence and Outcomes Study: Background

Since the beginning of the CAF mission in Afghanistan, personnel have been required to undergo Enhanced Post-deployment Screening, 90 to 180 days after their return.6 The goal of the screening process is to shorten the delay to care for those with deploymentrelated mental health problems. The process consists of completion of a detailed health questionnaire and a semi-structured interview with a mental health professional. Data collected during that process served as a primary source of surveillance data on the mental health impact of the mission. Over time, concerns about the completeness and reliability of those screening data were voiced. There was concern that they reflected symptoms captured on sensitive screening questionnaires as opposed to an actual clinical diagnosis. Publications showing the substantial under-reporting of symptoms at postdeployment screening emerged.7 As well, there was no information on how individuals who reported symptoms during screening were doing at some later point in time. Finally, there was little data on how the CAF’s renewed mental health system was function ing, particularly with respect to reducing the effects of mental disorders on force sustainability.

Those concerns drove the objectives of the study:

- Assess the cumulative incidence of servicerelated mental disorder diagnoses (“Operational Stress Injuries”) in personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan, over a prolonged period of follow-up;

- Assess the impact of a mental disorder diagnosis on military occupational outcomes such as career-limiting medical employment limitations (CL-MEL, that is, illness-related restrictions in duties that lead predictably to medical discharge); and

- Explore changes in the risk for adverse military occupational outcomes over time, in order to assess whether mental health services renewal has indeed translated into a better occupational prognosis.

Methods

The study began with the identification of the cohort of personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan over the 2001 – 2008 period.8 CAF personnel deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan in a variety of roles and to a variety of locations. Personnel, primarily from the Army, deployed in combat, security, development, support and training operations in varying capacities, largely in Kandahar province and in and around Kabul. Nearly all of the 158 CAF fatalities during the mission occurred among Army personnel in Kandahar province. Navy personnel largely deployed on a number of major vessels in the Arabian Gulf region, fulfilling a variety of fleet support, force protection, and maritime interdiction roles. Air Force personnel deployed largely to an air base in the United Arab Emirates and provided strategic/tactical airlift and long-range patrol/surveillance capabilities during the period of the study.

The cohort of 30,513 unique individuals was identified through linkage and cross-validation of several administrative databases.8 At the time, the CAF did not have an easily searchable mental health information system, so medical record reviews were required to capture any mental disorder diagnoses made in the CAF system after the first Afghanistanrelated deployment. A stratified, random sample of 2014 charts was reviewed by a research nurse, who also captured the clinician’s attribution of the diagnosis to the Afghanistan mission. Career-limiting medical employment limitations (CL-MEL, that is, persistent military occupational impairments that would almost certainly lead to medical release) and medical release from military service (medical attrition) were assessed through linkage with other administrative databases.9

A time-to-event analytic approach (survival analysis) was used to explore the cumulative incidence of Afghanistan service-related mental disorder diagnoses. The cumulative incidence represents the estimated cohort fraction so diagnosed prior to a particular point of time. Further analysis explored the relationship between mental disorder diagnosis and the development of CL-MEL, assessed as time from deployment return. Additionally, survival analysis was used to assess the relationship between mental health services renewal and delay to care on time to medical attrition among those with a mental disorder diagnosis. Survival analysis is a statistical approach used to model time-varying, dichotomous events, taking into account differences in follow-up time and loss to follow-up among subjects. The most common application of survival analysis in medical research is in cancer research, modelling for example literal survival time (time to death) or disease-free survival time (that is, time to documented recurrence) under two different treatment approaches. However, survival analysis has also been used in other medical applications (e.g., time to re-hospitalization after a myocardial infarction), as well as in non-medical applications, such as time to failure of a part, a piece of equipment, or even a complex system such as a computer network. One of the advantages of survival analysis is its ability to efficiently take into account loss to follow-up. For example, in the context of the present study, it was known that a particular participant had not experienced the outcome (e.g., diagnosis of a mental disorder) as of a particular date (e.g., the date of the review of their medical record), whereas their diagnostic status after than point was unknown. For the present study, two survival analysis methods were used: Kaplan-Meier probability estimates were generated for observed outcome rates (e.g., diagnosis) at successive fol

low-up times, and these were used to plot the estimated cumulative incidence of the outcome against follow-up time, for the population as a whole and among subgroups of interest (e.g., those deployed to different locations). The second method was Cox proportional hazards regression, which was used to explore the association of particular risk factors with the outcome, taking into account other potential confounding factors. Results from Cox regression are expressed as adjusted hazard ratios (aHR), a measure of relative risk. An aHR of greater than one indicates that the risk factor (such as a highthreat deployment location) is associated with a shorter time to the measured outcome relative to a specified reference category (such as a low-threat deployment location). An aHR of less than one indicates a longer time to event when the risk factor in question is present.

Key Findings

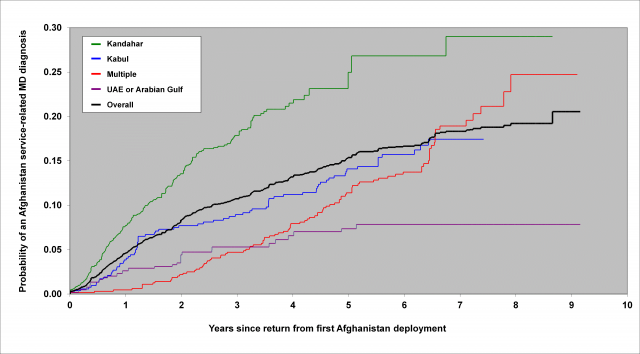

Cumulative Incidence of Afghanistan Servicerelated Mental Disorders (ARMD) ARMD was diagnosed by the CAF in 13.5% percent of the cohort over a median follow-up period of almost four years.8 An additional 5.5% were diagnosed with non-operational mental disorders or disorders related to other operations, meaning that 71% of those with a mental disorder diagnosis had one or more clinically attributed to the Afghanistan mission.8 The Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 1) shows that the fraction diagnosed by a particular point in time (that is, the cumulative incidence) increased over time but in a non-linear fashion: the rate of new diagnoses slowed substantially over time. The predicted probability of an ARMD diagnosis approached 20% after eight years of follow-up.8 PTSD was the most common ARMD (seen in 8% of the cohort, with or without various comorbidities).8

Fig. 1: Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of a mental disorder attributable to the Afgha nistan mission being diagnosed since return from the first deployment, by deployment location.

Fig. 1: Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of a mental disorder attributable to the Afgha nistan mission being diagnosed since return from the first deployment, by deployment location.

Risk Factors for ARMD

Clear differences in the risk of ARMD were seen as a function of deployment location, with deployments to Kandahar being associated with a high absolute risk (almost 30% by eight years) and a high relative risk (aHR = 5.6, relative to those deployed to the United Arab Emirates) of ARMD diagnosis.8 However, meaningful rates of ARMD were seen even among those who deployed to lower threat locations.8 Lower rank and Army service were also independently associated with higher ARMD risk.8 In contrast to findings from elsewhere, no increased risk was seen in women, reservists, or those with a greater number or longer cumulative duration of Afghanistanrelated deployments.8

ARMD and Career-limiting Medical

Employment Limitations (CL-MEL)

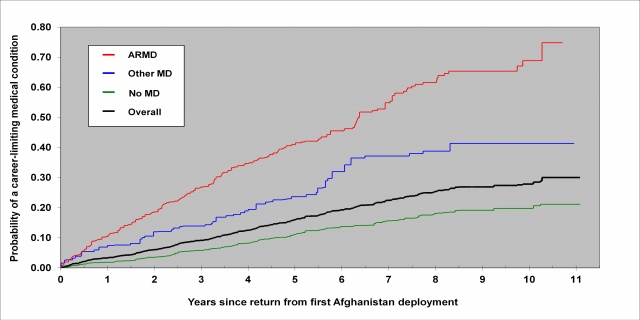

After five years of post-deployment follow-up, CL-MEL developed in 41% of those with ARMD vs. 11% of those without any mental disorder diagnosis (Figure 2).9 Those with nonAfghanistan-related mental disorders had an intermediate risk (24%).9 However, after ten years of post-deployment follow-up, it was estimated that 69% of those with an ARMD would develop CL-MEL. 9 Cox regression confirmed a significantly elevated CL-MEL risk (aHR = 4.9) for those with ARMD relative to those without a mental disorder diagnosis.9 Review of medical administrative data confirmed that a mental disorder was the primary or secondary contributor of the CL-MEL in 84% of those with ARMD who ultimately developed such limitations over the follow-up period.9

Fig. 2: Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of developing a career-limiting medical em ployment limitation (CL-MEL) by mental disorder diagnosis category.

Fig. 2: Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of developing a career-limiting medical em ployment limitation (CL-MEL) by mental disorder diagnosis category.

Effects of Mental Health Services Renewal

Secondary analysis of the study data showed that those diagnosed more recently (specifically, after April, 2008) had a lower risk of a medical attrition, relative to those diagnosed prior to this time.10 This difference persisted

after adjustment for potential confounders, including patterns of co-morbidity and disorder severity (aHR = 1.8).10 In addition, the delay to care decreased significantly over time, especially after 2009, and those with shorter delays to care (less than 21 months) had a lower independent risk of medical attrition.10

Discussion

Summary of Key Findings

This study confirmed the substantial impact of the mission in Afghanistan on the mental health of CAF personnel: Close to 20% of those who deployed in support of the mission are expected to be diagnosed with an ARMD within eight years of their return. ARMD accounted for a sizeable fraction (71%) of all individuals with a mental disorder diagnosis over the follow-up period. The most important risk factor for ARMD was deployment to a high-threat deployment location. For those deployed to Kandahar, the risk of ARMD approached 30% within eight years. However, meaningful rates of ARMD were seen even in those deployed to low-threat locations. ARMD was associated with a high absolute and relative risk (aHR = 4.9) of CL-MEL. Towards the end of ten years of follow-up, it was estimated that almost 69% of those with ARMD will develop CL-MEL. Over the study period, delays to care declined, and shorter delays to care were associated with a lower risk of medical attrition. In addition, those diagnosed more recently had a lower risk of medical attrition.

Comparison with Other Findings

Our findings cohere with the large body of literature showing that mental health problems occur in a significant minority of personnel who deployed in support of the conflicts in Southwest Asia.11;12 Substantial differences in study populations and methods among the

various studies (most of which use cross-sectional prevalence survey data) preclude formal comparison of rates. They also do not allow any conclusion as to whether CAF personnel have higher or lower rates relative to personnel in other nations.5;11;12 The association of combat exposure with the risk for post-deployment mental health problems is well-documented.13 We did not directly measure combat exposure, but we believe that the risk factors for ARMD we identified (highthreat location, lower rank, and Army service) are likely proxies for combat exposure.8 The high absolute and relative risk of military occupational impairments (captured by CLMEL and medical attrition in our study) also coheres with the results of many other studies.9;14–16 Again, differences in methods preclude any formal comparison of differences in risk in different nations. The CAF has emphasized the advantages of early care-seeking in its public messaging surrounding care-seeking for mental disorders. While it makes sense that treatment would be easier (and outcomes more favourable) in those who have not yet experienced the full extent of the “loss spiral” associated with trauma-related disorders,17 our documentation of an improved military occupational prognosis with earlier care is one of a very few such findings in the literature.18 Likewise, there are few other research findings with which to compare our own on changes in delay to care as a consequence of mental health services renewal.

Strengths and Limitations

The key strengths of this study include its use of a large representative sample from the complete cohort of all CAF personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan in a variety of roles over a significant period of time. Other studies have focused on subgroups of personnel (e.g., combat brigades19) and/or have focused on shorter periods of time,20 during which more homogeneity of deployment experiences is expected. We used diagnoses abstracted from medical records, as opposed to survey data capturing symptoms or diagnostic data obtained from less reliable electronic health data sources. A number of potential confounding factors not usually present in electronic data sources (e.g., clinical attribution to a particular mission, disorder severity) were included in the multivariate models, increasing their reliability. The prolonged follow-up period provided a more complete picture of the estimated cumulative incidence and of longer-term military occupational outcomes. Finally, the use of a time-to-event analysis approach made full use of the data and took into account differences in follow-up time.

The primary limitation is that the findings pertain only to diagnoses made within CAF mental health services during military service. Those who sought care only outside of the CAF (or those who sought care for mental disorders only in primary care) would have been missed, though available data suggests that this is uncommon for those with significant mental disorders. Those who sought care only after discharge would have been missed, as would those who remained in uniform but had not yet sought care. Hence, our cumulative incidence rates are systematic underestimates of the true fraction of personnel in the cohort who will be diagnosed with a servicerelated disorder. While the clinical attribution of the disorders to the Afghanistan deployment was clear in almost all charts, it is not clear how, precisely, clinicians arrived at this determination.

The use of a military occupational outcome (development of CL-MEL or medical attrition) was a pragmatic choice, but this outcome is an imperfect reflection of clinical status. Many may have had significant improvement in symptoms in a stable garrison setting, but concern remained about continued need for follow-up requirements or the risk for deterioration in an operational setting. We would have preferred to use a clinical outcome, but there were no reliable measures consistently available in the medical records.

Our analyses and findings related to positive changes in delay to care and military occupational outcomes over time could have been impacted by a failure to control for unmeasured confounders. More importantly, our attribution of these changes to mental health services renewal has intrinsic limitations— other unmeasured changes could have contributed. Finally, if one accepts mental health services renewal as the likely cause of those changes over time, we cannot say which precise aspects of the renewal drove those changes. Hence, it is difficult to apply these encouraging findings to other settings.

Implications

The high absolute risk of service-related mental disorders after traumatogenic deployments means that military and veterans’ organizations need to be prepared to deliver the required high volume of needed benefits and services. The precise cumulative incidence rates may inform resource allocation for the present operation and other similar operations in the future. That the risk of service-related mental disorders is highly dependent on deployment location (likely a proxy for combat exposure) means that the risk will be very unevenly distributed in different subgroups. The meaningful risk of ARMD even in those deployed to low-threat locations (like the United Arab Emirates) means that future

deployments of large numbers of personnel to such locations can still be expected to result in significant numbers of long-term psychiatric casualties.

The high risk of adverse military occupational outcome in those with ARMD reflects the reality of what happens when a serious, presently unpreventable medical condition with imperfect treatments collides with stringent occupational fitness standards.9 Opportunities for seeing better outcomes are constrained: Relaxing fitness standards could interfere with readiness or operational effectiveness. Primary prevention is appealing, but proven methods to achieve this do not yet exist. Better treatments for PTSD are clearly needed — too many patients do not accept, tolerate, or benefit completely from even the best available treatments, even if expertly applied. However, until such time as better treatments are developed and validated, clinicians will have to make the most of the treatments they presently have at their disposal. Hence, in the near term, the primary opportunity to see better outcomes lies in the realm of clinical quality assurance — ensuring that all patients receive optimal, evidence-based care.

The improvements in delay to care and in military occupational outcome over time are encouraging and suggest that the CAF has been on the right path in its mental health services renewal. However, an understanding of which precise aspects of its system are contributing to these favourable trends is needed if other organizations are to benefit from the CAF’s experience.1

Conclusion

The CAF mission in Afghanistan has taken a toll on the mental health of an important minority of the personnel who deployed in support of it. Military and veterans’ systems of care need to be prepared for this reality. Those with such problems have a high risk of being found unfit for continued military service, something that will be felt by the military human resources system (especially in highrisk units such as combat brigades) and by veterans’ service providers in the form of future, long-term demands for benefits and services. The most promising avenue to see better results is to ensure that all patients consistently receive optimal, evidence-based care. Mental health services renewal in the CAF has been found to be associated with shorter delays to care and better occupational outcomes. However, it is unclear which specific programs and services are contributing most to those encouraging trends. Such an understanding will only occur through indepth evaluation of the relevant programs and services.

Date: 12/08/2015

Source: MCIF 4/15