Article

Medical Force Protectionmy

What have we Learnt from Operation HERRICK in Afghanistan?

Medical Force Protection (Med FP) measures are important in mitigating morbidity and mortality in deployed forces. Historically, Disease Non Battle Injury (DNBI) accounts for significantly more morbidity than traumatic injury. However, how successful have we been in implementing such measures in Afghanistan? The co-authors who conceived and undertook 3 Med FP Audits in Afghanistan will describe the UK findings of the first audit and contextualise these in comparison to previous UK experience based on a presentation given at the NATO Medical Force Protection Conference in Budapest in 2014. The paper will conclude with some key recommendations that must be implemented for future campaigns to ensure that the Med FP lessons of Afghanistan are not forgotten and therefore negate the need to “reinvent the wheel”.

Introduction

For the United Kingdom Armed Forces, the Crimean War (1854 – 1856) was a significant milestone in recognising the importance of Disease Non Battle Injury (DNBI). It was a war that was a conflict in which Russia lost to an alliance of France, UK, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia. The legend of the “Charge of the Light Brigade” became an iconic symbol of logistical, medical and tactical failures and mismanagement. The reaction in Britain was a demand for professionalisation. Florence Nightingale gained worldwide attention for pioneering modern nursing while treating the wounded. Of the 21,000 UK deaths, 16,000 were attributed to disease. Indeed disease has always been the scourge of the majority of military campaigns(1). Over all future conflicts DNBI remained a greater cause of morbidity than Battle Injury. Fast forward, to the Falklands conflict in 1992 and the significant causes of DNBI were malaria (troops deployed through Sierra Leone), Noise Induced Hearing Loss, Musculoskeletal Injury due to ergonomic effects of heavy load carriage and Non Freezing Cold Injury.

Therefore it is important to conserve the fighting potential of a force so that it is healthy, fully combat capable, and can be applied at the decisive time and place. This consists of actions taken to counter the debilitating effects of environment, disease, and selected weapons systems through preventive measures for personnel, systems and operational formations, otherwise known as Medical Force Protection(2).

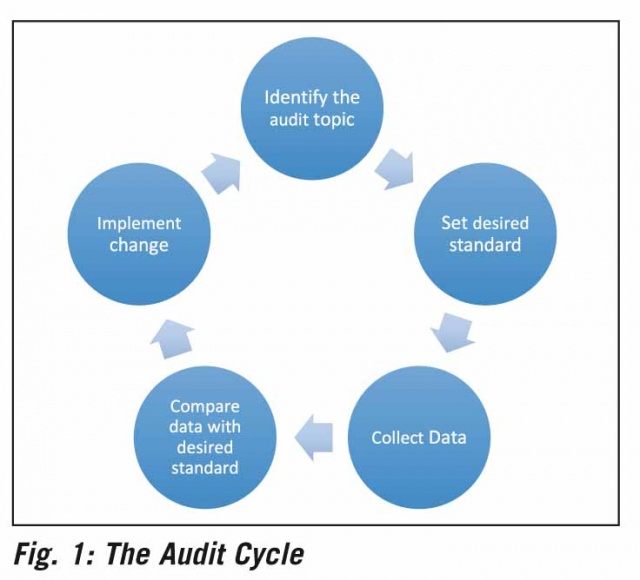

Audit is a cyclical and progressive process of ensuring that standards that have been set are adhered to and if required actions are taken to ensure that they are met in the future. It is a quality improvement initiative and inevitably means completing a full cycle if the intent of health improvement is to be met. Figure 1 illustrates a clinical audit cycle.

In 2008 the UK’s Defence Surgeon General and Army’s Adjutant General were concerned about the level of DNBI being sustained by British troops and questioned whether the Med FP processes in place were robust enough. The average impact was that 5% of the force would succumb to DNBI in a 6 month tour.

After a period of pre-deployment training the co-authors (a consultant public health physician) and another experienced Medical Officer (a consultant occupational physician) undertook a Med FP Audit in the Area of Responsibility that UK forces had. This paper will describe the methodology involved, the findings, recommendations and subsequent audits to complete the cycle.

Audit Methodology

The start point was to review all the Med FP policies and protocols that were in place to protect the UK Force through the stages of deployment – Force Generation; Force Maintenance; and Force Recovery. Then through a series of visits, interviews, focus groups and anthropological observation inside and outside of the theatre of operation the team were able to identify areas of compliance and non-compliance with Med FP intent. This included visits to the Main Operating Bases, Forward Operating Bases and Patrol Bases. The stakeholders responsible for Med FP policy were then presented with a formal report with recommendations. This then allowed the owners of the policy to take remedial action, where required, before a further audit looking at the areas where improvement was needed took place in 2010.

Findings from the 2009 Med FP Audit

The overall headline was that in general, there was good intent and effort to try and comply with Med FP policies and protocols but there were some significant constraints in the Force’s ability to comply entirely. For instance the maintenance of good personal hygiene in the absence of running hot water was inevitably difficult depending on the location a Service person was operating out of. Nevertheless recognising the constraints it was possible to identify some key themes covering the areas of information; infrastructure; human factors; training; and health protection.

Information

Information is paramount to enable monitoring, analysis of trends, and comparisons of performance against expected or desired standards. Certain aspects of clinical information during Op HERRICK were prioritised, such as information regarding battle casualties and those requiring rapid evacuation. However, DNBI and less time-dependent conditions were found to be reported o n a much more variable level.

The main method of reporting this data was through EpiNATO, which has been shown to vary significantly in its accuracy and completeness. In the operational footprint of Op HERRICK, it is only available on a geographic basis and therefore has less utility from a unit or functional perspective.

As well as the recording of disease occurrence, the impact that ill-health causes, such as working days lost (WDL) due to illness, is also recorded poorly and is thought to be underreported. Despite this, a large disparity of total WDL per 1000 per week was seen on Op HERRICK 9 ranging from ENT disorders causing 0.7 WDL/1000/week to intestinal infectious disease causing 11.2 WDL/ 1000/week.This lost capability will have both a local impact on combat power as well as overall manpower availability across the theatre of operations. Accuracy of this information is important so that commanders and planners have an accurate picture of available resources. It can also be used to draw attention to the Med FP problems that cause the largest loss of fighting force and highlights the need to commanders of the importance for improvements in those areas.

Work on improving health surveillance continues with the Defence Medical Services (DMS) playing a full part in the development of NATO policy and refinement of EpiNATO. This is achieved by having a DMS consultant working in the NATO Deployed Health Surveillance Centre (DHSC) in Munich.

Infrastructure

Both the management and accessibility of the information collected during Op HERRICK could be improved. The collection of data at smaller locations and how these data are related to the chain of command requires a higher level of efficiency. How these data are managed and presented to the chain of command should be a key consideration for any future deployment. The advent of the first Med FP audit and subsequent ones, including one on the DMS response to the Ebola public health emergency in Sierra Leone has now led to the establishment of a DMS Force Health Protection Board and a policy that will now require Med FP audits to be conducted on all enduring (> 3 months) UK deployments. Conducting these audits rigorously and effectively, will ensure that information transforms from data into useable intelligence, which can then be used to optimise operational capability.

Human Factors and Effects on the Individual

Consistent reports from commanders from Op HERRICK 9 were seen at all levels with concerns raised in respect to weight loss, injury through excess weight carriage, ear/hearing protection and general physical and mental degradation. As well as acute psychological reactions, the cumulative effect of living in a constant-stress environment was also reported as a potential influence on future health.

Heat injuries are also a significant factor in maintaining the fighting force. Strict acclimatisation protocols were adhered to for those arriving in theatre with a subsequent reduction in heat injures. Those who deployed from warmer environments such as Cyprus, had the opportunity to carry out their pre-deployment training in an environment which was similar to the operational theatre. This was undoubtedly seen as a large advantage in their immediate effectiveness when first deployed, compared to those who had undertaken their pre-deployment training in contrasting conditions to the operational climate.

Training

Training for deployments, particularly on enduring operations, is a key opportunity to address any concerns that are raised in the operational environment. With effective information and intelligence, mission specific changes can be made to optimise the operational readiness of deploying personnel. This involves simulation training such as casualty care, field training exercises involving simulated evacuation and Role 1 Validation.

These training environments can be used to simulate scenarios based on problems encountered in the operational environment such as an outbreak of gastrointestinal disease, a problem with water contamination or cases of malaria. This should be in addition to being familiar with existing operational guidelines and procedures. This helps team cohesiveness, increases confidence and provides a solid skill base for future challenges.

Health Protection

Pre-deployment immunisations for Op HERRICK were generally well performed, with the exception of anthrax. A common view became apparent that all personnel, not just health care workers, should be considered for immunisation against Hepatitis B. This was justified by a perceived increased risk, which would be encountered by providing first aid to local nationals, performing rummage searches and potential exposure during compound clearances. Following these concerns, the Hepatitis B policy was reviewed and updated to universal immunisation for Defence personnel. This highlighted the need for the monitoring and evaluation of extant policies in the deployed environment, ensuring a full risk assessment takes place in consideration of the local situation.

Gastro-intestinal infection was recognised across all formations and units as a major concern and as previously stated, led to the highest amount WDL/1000/week according to type of condition. Higher risk periods such as early in the tour and summer months were recognised. There was a suspicion that symptoms/ cases of gastrointestinal illness may be underreported, with variable use of antimicrobials and treatment seen amongst these patients. Although each location had a formulated plan regarding isolation facilities in case of an outbreak, no written major outbreak plans were seen and few of those spoken to were aware of any theatre wide plan or policy.

The use of alcohol hand gels was observed in both the clinical and non-clinical environment. There is some concern that use of these in the field is limited, may give false reassurance and reduce or prevent the use of more effective soap and water hand-washing methods.

Main Recommendations

Training

Individual skills in hygiene need to be improved with current pre-deployment training insufficient. This should be enhanced through regular training and yearly mandated packages. Medical officers require greater awareness of the practical application of medical force protection. This can be enhanced by an annual brief, or a separate physical or online training package. Training in a Role 1 environment with realistic constraints will also help in the preparation of deploying health teams.

In theatre, EHT can provide advisory training on their visits to various locations, taking into account the unique environment of each site whilst signposting to central policy.

Equipment

Clothing and ergonomics of personal equipment has been recognised as a required area of improvement. This includes hearing protection. Similar equipment to that which will be used whilst deployed should be available for troops in the preparation phase of pre-deployment training. This will allow adjustment and physical development to prepare for the increased physical requirement.

Personnel

Nutrition and weight maintenance requires attention with special consideration and attention given to those who operate for the majority of time in the more remote locations.

Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) has been broadly adapted and widely used as a management tool to help sign-post individuals requiring medical support following specific traumatic incidents. Further work is required to recognise cumulative daily stress and its potential longer-term effects.

Current guidelines of the management of gastrointestinal infections should be reviewed. The importance of its management as well as the reporting of any outbreaks should be discussed with medical and non-medical personnel prior to deployment. Clear case definition and robust guidelines from a clinical and logistical perspective should be well known by all and rehearsed prior and during deployment, with extra attention during higher risk periods.

Vaccination policies as well as risk assessment should be carefully reviewed to ensure health protection needs of personnel relates to the risk in the specific deployed environment.

Information

An integrated medical policy that covers collection, storage, management and dissemination of data is of key importance. Timely and accurate data is essential in order to produce medical intelligence, helping commanders to make optimal operational decisions.

Organisation and Infrastructure

During any reconfiguration of Headquarters, the concentration of medical assets and commanders and staff should be considered.

Public Health and Occupational Medicine should have active deployable assets to ensure that problems in specific environments can be identified and that health of the deployed force is being accurately depicted to ensure good quality medical intelligence. Environmental Health Teams should work in conjunction with these units to ensure a holistic approach. Coordination between these teams should be facilitated by an individual deployed as SO2 Med FP.

Conclusion

The wide-ranging nature of Med FP and its large influence on maintaining the fighting force means that it requires constant consideration and attention. Continuous reflection and refinement of issues encountered in Med FP can lead to large-scale changes. This was seen in the review and subsequent change of policy to universal hepatitis B immunisation for Defence personnel(3). Experience gained from Op HERRICK demonstrated improvements in some areas, but highlighted other areas that require improvement to ensure that the lessons learnt are not forgotten for future operational deployments.

- Greatest area for improvement remains deficiencies in information. The accuracy and use of data, particularly regarding DNBI requires attention and should be improved prior to future operations.

- Information gathered in the operational environment should be fed back to constantly improve pre-deployment training.

- Better information will allow wider monitoring of potential Med FP issues such as nutrition, hearing and musculoskeletal injuries. This will help to inform improvements in food, clothing and equipment based on medical intelligence.n

References: [email protected]

Date: 09/13/2016

Source: MCIF 3/16