Article

THE ROAD TO ACCREDITATION (Part 4 / 4)

LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE FIRST PUBLIC SECTOR ISO 15189 ACCREDITED LABORATORY IN GHANA.

RESULTS

Audit Scores and Accreditation

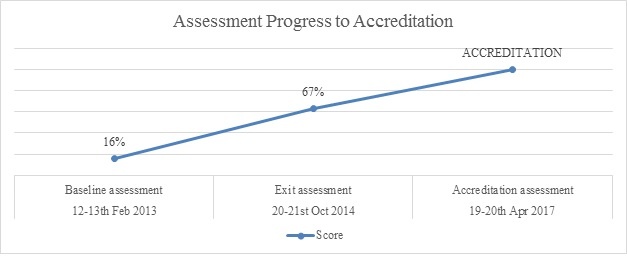

The outcome of the exit assessment in October 2014 by ASLM showed that the laboratory scored a total of 167 out of 252 points placing it at a two star rating. This was a significant increase from the 42 out of 257 points representing 16% and a zero star rating scored at baseline assessment in February 2013.

Progress of assessments

Progress of assessments

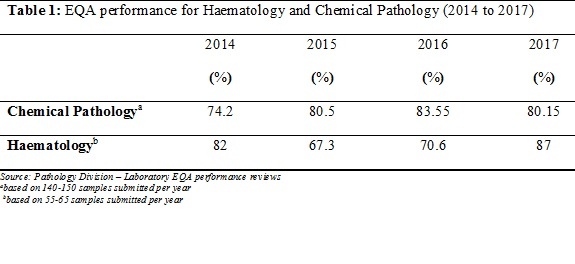

In addition to the assessment scores there was evidence to support the quality of laboratory test output in its EQA scores. The quality of laboratory test output showed continual improvement in its EQA test scores over the period.

DISCUSSION

High quality laboratory testing is critical for patient care, disease prevention and disease surveillance14. Although the majority of laboratory testing are done in public sector laboratories, no laboratory in the public sector in Ghana has previously or until recently been accredited to any national or international standard5,8. The only two accredited laboratories in Ghana are private enterprises. In fact, in sub-saharan Africa, only two public laboratories have been accredited previously to international standards; one each in Namibia and Botswana. There is no public sector accredited laboratory in the rest of sub-saharan Africa5,9.

The significantly low scores of the laboratory at its baseline assessment was clear indication of the poor documentation practices, lack of EQA implementation, inadequate quality control practices, among others. It was however clear that by using the stepwise approach as described in the SLMTA program it was possible to establish an efficient QMS and get accredited. The laboratory was encouraged by the possibility of being the first public sector laboratory to receive international accreditation recognision and contribute better to health service delivery. The evidence was therefore clear with an observed greater than 50% improvement between baseline and exit assessments.

Focus was not only on improving audit scores but improving quality of result output. Progress in the EQA results was further evidence that a significant improvement in the LQMS level of a laboratory can have a significant improvement in the quality of its test results.

An effective mentorship program just like an effective quality assurance department in the laboratory plays a significant role in the accreditation acquisition process. The mentorship program did not only serve as a guide but developed strategies to enable the laboratory meet most requirement of the LQMS. Key among them is the development and verification of in-house tools such as document control, calibration, verification and quality control tools. These involved the use of spreadsheets which enabled the laboratory monitor its analytical processes closely.

Collective involvement has always been an effective tool in change process15 as was observed in the Pathology Division. The team shared all plans, actions and assignments of the quality improvement process. This helped to eliminate the erroneous notion that the change process was “someone else’s job”. Weekly laboratory management meetings and monthly SLMTA meetings with Hospital Command were crucial.

The laboratory was bedeviled with several challenges in the attainment of accreditation. One such concern, which still remains unresolved is that of staff attrition. This had a significant impact on the progress rate and audit scores causing it to rise slowly. As a military facility, personnel are often posted on military and allied duties resulting in significant slowing down of laboratory processes. These create inconsistencies among the persons managing the quality system. To address this situation, the laboratory has developed staff orientation and training programmes to constantly keep old and new staff abreast with the status and requirement of the LQMS.

Challenge Identified | Solution |

Reluctance to the change process, with the assertion that the process was for a selected few. | In-house Continuous Education sessions were continually organized. Staff were trained on the improvement process, ISO 15189, requirement of the SLIPTA checklist, Good Clinical Laboratory Practices and Laboratory Quality Management Systems (LQMS). |

Notion that completion of occurrence reports had punitive consequences. | Group training and one-on-one coaching with staff on the importance and benefits of occurrence reports was continually and consistently done. |

No accredited public sector laboratory to look up to and to learn from. | One mentor with the exclusive duty of researching and providing guidance was engaged throughout the process |

Service interruptions due to reagent stock outs as a result of delays by suppliers and bureaucratic procurement processes. | Some level of financial autonomy was given to the laboratory to ensure continuous supply of reagents and consumables. |

High staff attrition. | Each appointment on the Quality Steering Committee had two persons sharing the responsibilities. Consistent staff training, orientation and re-orientation. |

Staff without requisite qualification involved in testing. | Opportunities created for staff without appropriate qualification to have appropriate training. |

Table 1: Major challenges to the improvement process and solutions implemented

Conclusion

The attainment of ISO accreditation in the public sector laboratory in Ghana can therefore be said to be a possibilitiy. The number of ISO accredited clinical laboratories in the country has also increased providing confidence and guidance to other public sector clinical laboratories to aim and achieve higher levels of quality. Using the SLMTA program and the SLIPTA approach coupled with management commitment, team work and efficient mentorship more laboratories can attain accreditation and increase the quality of laboratory service delivery in Ghana and in Africa.

Limitations

This is a descriptive study showing how one facility implemented quality management systems in a resource limited country. A significant number of external assessments were conducted within short intervals which therefore affected the amount of time and effort required in implementing corrective actions. External funding for the implementation of the programme was cut which affected the progress of the process as the hospital was compelled to source funds to continue the process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge the entire staff of the Pathology Division – laboratory for their relentless commitment in this major transformation of the laboratory and for the medical laboratory profession in Ghana as a whole. We are thankful to the Military High Command for their support and to the Hospital Command for believing in the laboratory and giving it the needed support and encouragement. We extend our appreciation to all partners especially United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States-Deployment Health Assessment Programme (US-DHAP) and HIV/AIDS Program who provided funds for the SLMTA implementation program; John Hopkins Programme for International Education in Gynaecology and Obstetrics (Jhpiego-Ghana) for providing funding for the accreditation application process; and Global Health Systems Solutions (GHSS-Ghana) and Ghana Health Service (GHS) for their immense technical support.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ Contributions

R.D.F. mentored the laboratory and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.A. directed the laboratory and reviewed the first draft. I.T.K. and A.M.Y. managed the LQMS and reviewed the first draft. R.B.O and C.B. managed the laboratory and reviewed the first draft. L.X.AD., J.B., K.B., J.A., C.B., S.K., M.M., R.K., M.A.A., A.M., J.A., K.A., A.A., F.H., G.D., G.N., N.Y.F.S., A.A.P., provided technical assistance and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. A.A., A.B.A.K., R.A., M.K reviewed the final manuscript.. All authors contributed in writing the article.

References

1. Olmsted, S., Moore, R., & Meili, H. (2010). Strengthening laboratory systems in resource limited settings. American Journal for clinical pathology, 134(3)374-380. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1309/AJCPDQOSB7QR5GLR

2. 37 Military, H. (2017, October 12). Military Hospital. Retrieved from www.gafonline.mil.gh

3. Andriric, L. R., & Massambu, C. G. (2014). One laboratory's progress towards accreditation in Tanzania. African Journal for Laboratory Medicine.

4. Peter, T., Rotz, P., Khine, A., Freeman, R., & Murtagh, M. (2010, Oct). Impact of Laboratory Accreditation on Patient Care and the Health System. Am J Clin Pathol, 134(4), 550-5. doi:10.1309/AJCPH1SKQ1HNWGHF.

5. Schroeder, L., & Amukele, T. (2014). Medical laboratories in sub-Saharan Africa that meet international quality standards. Americal Journal of Clinical Pathology, 141(6):791-795.

6. WHO. (2017, November 16). World Health Organisation. The Maputo declaration on strengthening of laboratory systems. Retrieved from World Health Organisation: http://who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/Maputo-Declaration_2008.pdf

7. Gershy-Damet, G., Rotz, P., Cross, D., Belabbes, E., Cham, F., Ndihokubwayo, J., . . . Nkengasong, N. (2010). The World Health Organisation African Region Laboratory Accreditation Process: Improving the Quality of Laboratory Systems in the African Region. Kigali Conference.134, pp. 393-400. Kigali: Am J Clin Pathol. doi:10.1309/AJCPTUUC2V1WJOBM

8. Nkrumah B, V. d. (2014). Building local human resources to implement SLMTA with limited donor funding: The Ghana experience. Afr J lab Med(214), 7. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.214

9. Gachuki T, S. R. (2014). Attaining ISO 15189 accreditation though SLMTA: A journey by Kenya's National HIV Reference Laboratory. Afri J Lab Med, 9. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.216

10. Yao, K. (2010). Improving Quality Management Systems of Laboratories in Developing Countries: An Inovative Training Approach to Accelerate Laboratory Accreditation. Am J Clin pathol, 134:401-409. doi:10.1309/AJCPNBBL53FWUIQJ

11. Viegas SO, A. K. (2017). Mozambique's journey towards accreditation of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory. Afr J Lab Med, 6(2). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.

12. Maruta, T., Rotz, P., & Trevor, P. (2013). Setting up a structured laboratory mentoring programme. Afr J Lab Med, 2(1), 7. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v2i1.77

13. Maruta, T., Motebang, D., Qanyoike, J., Peter, T., & Rotz, P. (2012). Impact of mentorship on WHO-AFRO strengthening Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA). Afr J Lab Med, 1(1), 6. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v1i1.6

14. World Health Organisation, C. a. (2011). Laboratory Quality Management System: Handbook. Geneva: WHO.

15. McAlearney AS, T. D. (2014). Organisational coherence in health care organisations: conceptual guidance to facilitate quality improvement and organisational change. NCBI, 23(4):254-67. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000044.

Authors: Dr. (Col) Seth Attoh1, Mr Raymond D. Fatchu1, Mr I.T. Kodjoe1, Lt Col Richardson B Owusu1, Maj Cynthia Boateng1, Capt Alhassan M Yakubu1, Maj LX Adusu-Donkor1, Maj Joseph Boafo1, Mrs Patience N Matey1, Ms Sarah Kwao1, Mr John Ani-Amponsah1, Lt Cdr (Dr) Emmanuel Sarkodie1, Maj Kwasi Boaheng1, Flt/Lt Mary McAddy1, Capt Richmond Kyei1, Maj Monica Asante Addo1, Mr Anthony Mason1, Mr Joseph Addy1, Maj Kingsley Ackah1, Maj Anita Adjabu1, Lt Col (Dr) Fred Hobenu, Sgt Godwin Dutsyo1, Mr Godwin Nyarko1, Capt Nana Yaa F Snyper1, Capt Adu Ahenkan Poku1, Capt Christina Banamwin1, Prof Andrew Adjei2, Dr Amma Benneh-Akwasi Kuma2, Richard Asmah3, Marian Kpakpah3

Author’s affiliations: 1Pathology Division-Laboratory 37 Military Hospital, Accra-Ghana, 2College of Health Sciences University of Ghana, 3School of Allied Health Sciences- College of Health Sciences University of Ghana

Date: 04/06/2018