Article: Lt Gen (Rtd) Professor Martin CM Bricknell CB OStJ PhD DM MBA MA MedSci Professor of Conflict, Health and Military Medicine Conflict and Health Research Group

Analysing Civil-Military Command and Control in the Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our countries and led to an unprecedented mobilisation of national resources including the use of armed forces to augment civilian health capacity. This health crisis has put immense pressure on military medical services both to ensure force health protection and health care for members of the armed forces, and to augment capacity of the civilian health

system (1). This has raised the profile of the medical staff function alongside the clinical capabilities of the military medical system. It is important to consider the contribution of military medical leaders and planners to the medical command, control and liaison systems that have been

established across many government ministries beyond the Ministry of Defence in order to determine whether these should be retained for the future. This paper proposes a

generic ‘command and control’ model for interpretation of national responses in order to facilitate sharing of observations. It complements our emerging work to develop a generic taxonomy of civil-military activities in support of national response to the COVID-19 response.

Just over one year from the onset of the crisis, insights from internal reflective lessons learned processes are beginning to emerge into the public domain through presentations at conferences, academic papers and other communications. This information provides an opportunity to compare between nations and to build generic models of civil military responses so as to provide insights that can be used to inform national and international interpretations of the crisis. This paper summarises national presentations on the military medical contribution to civil-military command and control arrangements from recent international conferences including the DiMiMED International Conference on Disaster and Military Medicine conference (16-17 Nov 20), Australasian Military Medical Association conference (25-27 Nov 20), the AMSUS Conference (6-10 Dec 2020) and the combined ICMM Regional Assembly of the Pan-Arab and Maghrebian Regional Working Groups of Military Medicine (9-10 Feb 20). This summary will provide generic insights that apply across nations, recognising that the solution selected by each nation will be the result of specific local factors.

Outline to Responses to the Outbreak

There is an emerging consensus on the important contributions made by military medical services in support of national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (2). Initially there was a short-lived burst of international emergency repatriation of citizens from outbreak zones across the world. Within countries, the first phase was focussed on the design and implementation of force health protection (FHP) measures to minimise the risk of COVID-19 to armed forces personnel that were compliant with wider national policies. This included adjusting ways of working (social distancing, working from home etc, cohort isolation) in order to maintain the minimum necessary military capability and capacity to meet essential defence tasks. The second phase was the mobilisation of military assistance to the civilian response including: procurement of personal protective equipment and other essential emergency supplies, establishing diagnostic testing and health surveillance systems, and augmenting civilian health service capacity (alongside adjusting the capabilities and maintaining the capacity of the military health system). As the first wave diminished, effort shifted to restoration of military activities through managing the risk of COVID and supporting research efforts (especially the development of COVID vaccines). Although the second wave was predicted, the severity exceeded expectations and resulted in the re-imposition of many of the control and response measures from the first wave. At the time of writing, many Western countries are anticipating a reduction in control measures as national vaccination campaigns begin to provide immunity to the most vulnerable members of their populations. Military personnel are often a vital additional source of national vaccination teams. Overall, civil- military planning across all levels of government has been an essential pre-requisite to the efficient use of military capabilities.

Command and Control – Civil-Military Medical Co-operation in COVID-19

The role, functions and capacity of medical staff branches is the subject of significant debate within military medical services (3). Allied Joint Medical Doctrine provides a description of the potential structure of a medical staff branch (4). This covers the generic staff functions (J1-9) including links to the civilian health system. During military operations, military support to civilian authorities is considered to be an option of last resort though arrangements exist for civil-military cooperation through CIMIC or UN CMCoord depending on the system for information sharing (5). Prior to the COVID-19 crisis there was an emerging debate on civil military co-operation in managing future global public health risks, primarily focussed on the experience of South and East Asian countries (6). The reported experience from the COVID-19 response shows that the armed forces and military health system have been an integral component of national response as equal partners or leaders within countries’ health economies. Thus ‘humanitarian frameworks’ that emphasise neutrality and operational independence as a separation between security actors and wider government actors have not been appropriate in the context of the COVID-19 crises in countries that have functional governments.

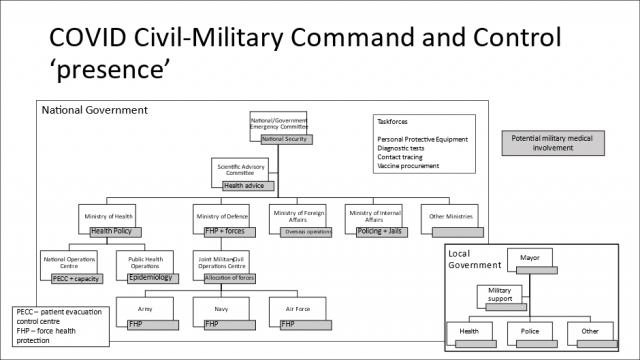

Military medical personnel have had important roles in leadership and staff appointments across government, both within Ministries of Defence, across other government ministries and specific taskforces. This has been a unique level of civil-military co-operation between different components of national health systems outside of full-scale war. This experience might provide evidence of the level of co-operation necessary during a war and might also indicate new relationships that need to be sustained after the COVID-19 crisis has subsided. Based on national briefings from the conferences described in the introduction, Figure 1 shows the potential ‘points of presence’ for military medical personnel across governments as shaded boxes linked to every functional component of government. These linkages have occurred at both the national (or federal) level of government (which is the normal level of civil-military collaboration) and also at the local (or regional government) level for the tactical control of military support. This distinction has been important in many countries where funding (taxation or insurance) for healthcare is a delegated function of government with the national Ministry of Health being responsible for policy, regulation and governance but not direct management of health facilities.

Most governments have established a COVID-19 response committee at the national, cross-government level, either de novoor based on existing disaster management structures. In some countries, this has been led by a senior military fi gure (and even the Surgeon General). This committee has the responsibility for leading and managing the whole national COVID-19 mitigation ‘campaign’ across all government departments. Just like in military planning, many governments have created designated national ‘Taskforces’, to manage discrete components of the strategic campaign plan to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. These have included procurement of PPE and essential medical supplies, diagnostic testing, contact tracing, quarantine management, and vaccine research and procurement. Many countries have also turned to military personnel to lead or augment the planning and delivery capacity of these Taskforces.

Many countries have also established a Scientifi c Advisory Committee to provide technical advice to the national emergency committee. Armed forces experts in medical intelligence, biological weapons research and public health may have been co-opted as members. Some nations have substantial military bio-medical research institutions that have also conducted primary research relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic covering vaccine development, therapeutics and epidemiology (especially in military populations).

Ministries of Defence often relegate their Surgeon General and medical staff branch under the personnel or logistics function. However, this health crisis has raised the prominence of the military health system and technical health advice which has created a substantial new demand for medical staff across the whole military staff structure. If not fi lling a national role, senior medical staff have been attending military committees at the highest level. Medical personnel and units have been a critical part of military assistance to the civil authorities. This has often been co-ordinated through a designated military-civil assistance taskforce under a designated Joint commander and operations centre (i.e. commanding army, navy and air force personnel). The commands of the Services (Army, Navy and Air Force) have had a similar demand for medical staff advice, especially in regard to COVID-19 protection measures and response to outbreaks in military units. This analysis does not consider the second order impact on the internal structure and function of the military medical services. This topic merits a discrete analysis in its own right.

The COVID-19 crisis has reinforced the importance of military health systems as a component of a country’s health economy and its potential role as a source of strategic reinforcement to the civilian system (7). This contrasts with the prevailing perspective before COVID-19 that suggested that the civilian health system could be a source of strategic augmentation to the military health system during confl ict through the mobilisation of military Reserve forces. All countries have had to re-confi gure their health system to care for patients with COVID-19, including expanding capacity and deferring care for non-COVID-19 medical conditions. Whilst intensive care capacity was the initial emphasis for most health systems, the importance of discharge pathways, nursing and social care has become increasingly relevant. Furthermore, as local health systems became overwhelmed by intense outbreaks, it became necessary to manage patient regulation at a national level, including all forms of medevac (road, rail, sea and air). This has required systems level thinking that mirrors the military approach to a concept of medical support based on pathways of medical care (8). Military medical personnel have augmented Ministries of Health across many departmental functions and demonstrated the transferability of many components of strategic medical planning into the civilian context. This has also enabled Ministries of Health to understand the breadth and capacity of the military health system to augment the civilian sector and ensure efficient matching of military capabilities to tasks.

At the beginning of the outbreak there was a surge of military support to Ministries of Foreign Affairs to assist with the repatriation of national citizens from epicentres of COVID-19 outbreaks across the world. This included medical oversight of exposed and symptomatic patients during evacuation and quarantine. The armed forces have also provided augmentation to local authorities in overseas national territories. Support to international partner countries has become an important diplomatic tool for strategic purposes with many countries providing military to civilian and military to military medical assistance alongside pure civilian partnerships as support to the COVID-19 crisis. This type of health diplomacy might become a significant feature of international engagement into 2021 and beyond.

The final inter-ministry relationship to consider is between the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Many countries use their armed forces as a source of strategic reinforcement for their police and other internal security forces. Whilst this does not usually directly impact military medical services, it is worth considering some of the health implications of the COVID-19 crisis on the internal security system. The first issue is the relative risk of unmitigated exposure to the coronavirus during internal security and policing activities. This make result in officers conducting riot control, border security, prison duties or other public facing roles being at higher risk of contracting the disease compared to other government workers. The second issue is the specific responsibilities of government to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 transmission inside prisons, detention centres and other locations where individuals are held under state control. Both of these topics require designated medical advice and staff in support of these security functions.

The same breadth of military support to ‘command and control’ has also been seen at the local government level, especially for the tactical management of military assistance. There is even greater international variation in subordinate systems of government than at national level. The image of ‘local government’ in Figure 1 is purely illustrative in order to highlight the potential for additional involvement of military medical staff assistance at this level of government.

COVID Civil-Military Command and Control ‘presence’

COVID Civil-Military Command and Control ‘presence’

Observations

Based on the description above, civil-military co-operation at a national level and local level has been an important activity for military medical services and has required significant number of personnel to be deployed from their normal role. The image at Figure 1 might be useful as an indicative model for analysis of civil- military collaboration. This can be expanded to cover all ‘points of presence’ where military medical staff have provided augmentation or liaison to civil authorities. International comparisons can then identify those points of presence that have occurred in every country and those that have been unique in the context of individual countries. This process can also identify those roles that need to be maintained as the minimum military requirement for civil-military collaboration for future health or other national emergencies. It will also identify the core competencies required of military medical planners in global health and health systems so that personnel can be better trained for these roles in the next emergency.

References with the author

Date: 12/22/2021

Source: EMMS 2021