Article: Kaat Goorts

Human Performance in Defence: the road toward sustainable readiness

A Growing Need for Holistic Support

Modern military operations place increasing physical and mental demands on personnel. As the Belgian Defence faces high attrition rates and ongoing recruitment challenges, especially among early-career soldiers, the importance of targeted support programs has never been greater. Mental and physical strain has emerged as a leading cause of early dropout, with injuries – primarily affecting the lower limbs – closely following. The urgency to sustain performance and reduce long-term losses has led to the emergence and gradual institutionalization of the Human Performance Program (HPP) across high-performance units in Defence.

Training in climatically challenging conditions is often a daily reality for high-performance profiles within Defence. Supporting them with appropriate monitoring and, where possible, adjustments is therefore desirable within the Human Performance Program. (source: Belgian Defence Arctic training – Gert-Jan D’haene)

The Belgian HPP began in 2018 within the Special Forces Group (SF Gp) as an experimental initiative rooted in academic research. Sleep deprivation and inadequate recovery were highlighted as key challenges for elite military functions. By 2021, the program had evolved, supported by the Directorate-General Health & Wellbeing, aiming to support all high-performance units across Defence.

In 2024, the NATO Special Operations Medical Leaders Handbook dedicated a full chapter to HPPs for Special Operations Forces (SOF), confirming the international relevance of the Belgian approach. That same year, an article in the Belgian Military Journal (BMT) drew national attention to the growing maturity of the HPP initiatives and their potential for broader application.

The United States Army Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) program exemplifies a similar structure, integrating physical, mental, nutrition, sleep, and spiritual domains into combat readiness. This cross-disciplinary effort has shown measurable improvements in soldier performance, retention, and injury prevention.

Human Performance as a Defence strategy

The Belgian Defence describes its HPP as a strategic, multidisciplinary initiative designed to enhance resilience, capacity, and performance across the physical and mental spectrum – not only during missions, but before and after as well. The program is built around three key pillars: effective load management, the development of multidisciplinary teams, and the promotion of awareness.

At its core is the principle of load management, which aims to ensure a balanced relationship between the demands placed on personnel and their capacity to respond. Rather than simply reducing attrition, the HPP seeks to equip military staff with the tools and support they need to meet the challenges of service, and grow through them. Load management involves systematically measuring and adjusting both mental and physical strain in training, operations, and selection processes. Tools such as wearable devices and smartphone applications are used to collect daily biometric and subjective data. This facilitates personalized feedback loops and allows instructors and medical teams to intervene when necessary.

In SOF training, such methods have helped to distinguish more clearly between the training and selection phases – two stages that often place overlapping demands on candidates. By using objective data to monitor load and recovery, instructors can ensure that the training phase focuses on developing skills and physical capacity without overwhelming candidates, while the selection phase remains focused on evaluating performance under stress. This clearer separation prevents injuries, optimizes performance development, and makes more effective use of candidates’ potential. Similarly, in fighter pilot training under the Belgian Aircrew Performance & Enhancement Program (APEP) – an HPP initiative within the Belgian Air Force – load monitoring is used to address common issues like neck and back pain, using structured screening, coaching, and the use of biofeedback.

While biofeedback-based interventions offer a wide range of possibilities, their effective implementation at scale presents challenges. Integrating wearable technologies, interpreting the collected data across large groups, and doing so without disrupting daily routines requires careful planning and coordination.

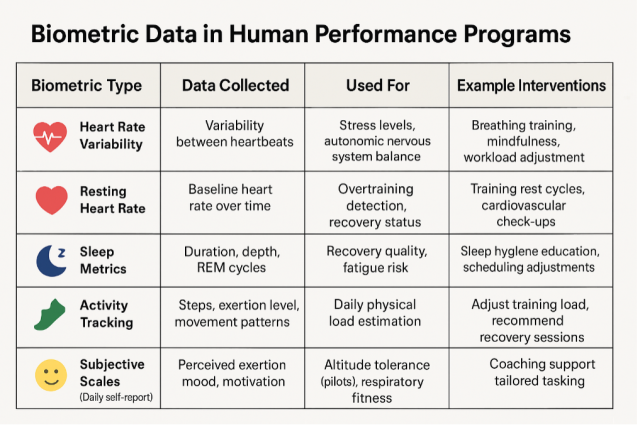

To illustrate the practical value of this approach, Figure 1 presents examples of easily interpretable biometric data. These data points allow for straightforward interventions that can produce significant impact with minimal effort.

Figure 1: Biometric data useful in Human Performance Programs(AI generated by the author)

Each HPP implementation is grounded in the multidisciplinary team collaboration of physicians, physiotherapists, psychologists or mental trainers, physical training instructors (PTIs) led by a human performance manager (HPM). Regular interdisciplinary meetings, data sharing (within ethical boundaries), and coordinated intervention plans are foundational to modern idea of ‘holistic care’. The idea of holistic care is that different disciplines should work closer together because overlap exists and interventions in each discipline will have an impact on each other.

To support a sustainable ecosystem, training for HPMs and other team members are being developed and aligned with evolving mission demands. Instructors, particularly PTIs, are being reskilled in areas such as load management.

In addition, it is important to raise awareness about the principles of HPP so that basic knowledge on resilience training and principles of load management is implemented in all foundational military education – ensuring that candidates, instructors, and support personnel internalize performance and wellbeing as interconnected priorities. For young candidates this information is meant to use for self-care, while instructors should be able to tackle these issues on a group level.

The Belgian HPP efforts are primarily targeted on high-performance environments, such as SOF units (e.g., SF Gp, Paratroopers) and some aircrews. These units receive benefit from a full-spectrum HPP implementation, which includes wearable monitoring, access to a complete multidisciplinary team, and leadership engagement.

In military schools, where basic training takes place, multidisciplinary teams are also implemented, which are supported by a HPM who acts as their coach. Here, the team’s primary objective is to prevent candidates dropouts caused by overtraining. The focus is placed more on the group and the overall training program, rather than on intensive individual follow-up.

Foundations for Success – or Keys to Failure?

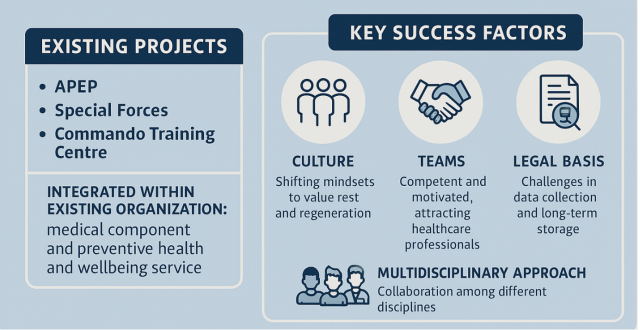

Implementing a robust and effective human performance strategy is as much about cultural transformation as it is about science and structure. The success of load management systems and multidisciplinary collaboration rests on several essential, but often fragile, conditions. When neglected, these same pillars can become the cracks through which the entire system falters (see Figure 2).

First and foremost, shifting mindsets is critical. A high-performance culture cannot exist without a parallel culture of rest, recovery, and regeneration. This means challenging long-held attitudes within both training environments and operational units – where endurance is often still mistaken for resilience, and where rest is seen as weakness rather than necessity. Embedding recovery strategies into military pedagogy and leadership thinking is fundamental if load management is to be more than just a monitoring tool.

This cultural evolution begins in the basic training of instructors and recruits alike. Awareness programs around mental and physical fitness must be institutionalized, with structured educational pathways that emphasize human sustainability as a professional skill.

Modern technology is now well established in various aspects of military training. Wellbeing monitoring is often not part of this wave of innovation. Human Performance Programs combine wellbeing with performance, making the topic more suitable for military culture. (source: Belgian Defence indoor SOF training – Adrien Muylaert)

Second, there is a need for motivated and competent teams. Even the best-designed systems will fail if there are no skilled people to operate them. A persistent shortage of healthcare professionals, particularly physicians, puts the sustainability of HPP at risk. While load management and health tracking systems generate critical insights, these mean little without trained professionals to interpret the data, adjust training regimens, and provide timely interventions.

Figure 2: The Human Performance Program in the Belgian Defence 2025 (AI generated by the author)

To attract and retain these professionals, the Belgian Defence must rethink the way it positions medical roles. Offering a compelling work-life balance, territorial postings, team-based collaboration, intellectually stimulating work environments and market-conform remuneration are no longer optional – they are essential. Moreover, not all team members need to be uniformed personnel; civilian professionals with the right skillsets and motivation can offer significant value, especially in regionally embedded support roles or in policy development positions.

The very nature of multidisciplinary work – based on shared knowledge, horizontal communication, and collaborative decision-making – often clashes with the traditional hierarchical structure of defence organizations. This challenge becomes even more complex when multiple services are involved. In the Belgian context, this tension is particularly evident. The curative health services (including medical treatment and healthcare policy) fall under the Medical Component while the preventive health services (health and wellbeing policy) operate under the Directorate-General of Health and Wellbeing. These two distinct organizational structures create artificial boundaries that complicate coordination and hinder shared responsibility. Further adding to the complexity is a third authority recently introduced at the staff level: the medical advisor to the Chief of Defence. This role, while intended to provide strategic guidance, inevitably overlaps with the mandates of the other two bodies–introducing additional tension and ambiguity in roles and responsibilities.

In practice, a HPP requires a fluid model where healthcare professionals, physical trainers, and instructors co-create interventions. This collaborative model, while proven effective in a few test-units, is difficult to replicate across an entire military force unless structural reforms allow for greater integration and authority-sharing.

A final – and perhaps the most technical – challenge lies in biomedical data collection. Effective load management inherently requires collecting physiological subjective data. While the intent is clearly benevolent – to protect and empower personnel – the legal framework in multiple European countries currently prohibits employers from collecting such sensitive health data outside of strictly defined contexts such as research projects that are limited in time.

This forces defence organizations to operate under the guise of research projects, using informed consent procedures that limit the scope, duration, and institutional use of the collected data. Long-term monitoring and systemic analysis – critical for identifying trends and evolving policy – become nearly impossible. A European legal framework that acknowledges the unique role of defence organizations in supporting performance and wellbeing is urgently needed if HPPs are to reach their full potential.

Toward a Culture of Sustainable Excellence

In summary, the Belgian HPP shows immense promise. It draws from evidence-based practices, leverages interdisciplinary expertise, and is backed by both scientific rationale and operational need. But as this reflection reveals, the foundations of success – culture, people, structure, and legality – are also potential keys to failure if not actively and continuously addressed.

The future of defence readiness lies not only in advanced equipment or increased recruitment, but in treating human potential as a renewable resource – one that thrives on care, collaboration, and ethical intelligence.

The path ahead is complex, but with sustained investment, courageous reform, and commitment to working across organizational structures, HPPs can evolve from promising pilot projects into a core pillar of defence philosophy.

References available on request from the author

Author:Dr. BioMed. Sc. Kaat Goorts, PhD

Directorate-General Health and Wellbeing, Belgian Defence

1140 Brussels (Evere), Belgium

Email: [email protected]

Date: 07/01/2025

Source: EMMS Magazine 2025